When did the idea for this collection start coming together? What was the process like of narrowing down your work in order to compile the final table of contents?

GWENDOLYN KISTE: Thank you so much! Having a collection is still such a surreal experience. Thrilling beyond belief, but surreal to be sure. Over the last year, several of my beta readers had encouraged me to put together a collection, but I wanted to wait until the right opportunity came along. To be honest, I thought it would be at least another couple years before I had a collection; I’ve only been a published author for less than three years, and my first professional sale was only eighteen months ago, so sometimes, this whole career feels so new. Then my incredible editor Jess Landry approached me and asked if I would be interested in submitting a project to her. As a huge fan of JournalStone, I obviously jumped at the offer, since this was exactly the opportunity I’d been hoping for.

As for the table of contents, I already had a list of the stories that most resonated with me. (As a strange aside, months before I even started to put the collection together, I actually had those titles jotted down on an index card and pinned to my bulletin board over my desk; they were there as a visible reminder of “hey, you can write decent stories sometimes!” on the days when the words simply weren’t happening.) However, just to be sure that I had a good perspective on my own work, I did go back and ask my beta readers which of my pieces were their favorites. Ultimately, everyone was in agreement that the table of contents I envisioned for the collection was the right one, so that made me even more confident that these were the best stories for this book.

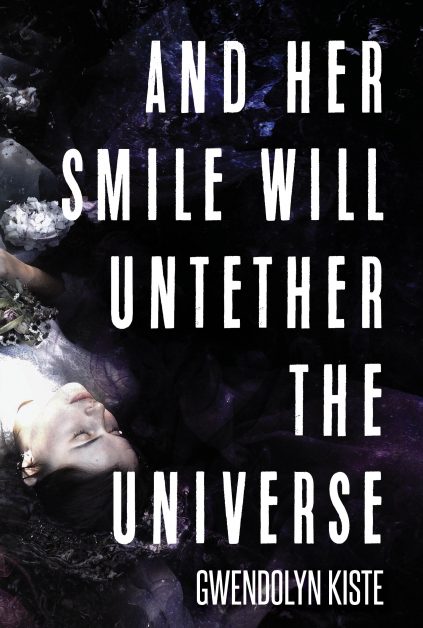

HN: The evocative title of your collection—“And Her Smile Will Untether the Universe”—is also taken from one of the stories. How did you decide which story would be the titular one? Were there other names you bandied about before settling on this one?

GK: This particular story was the last one I wrote for the collection, and I knew even before it was done that it was probably going to be the title story. It was an idea that had lived in me for a long time: a surreal tale of a murdered ingénue and a movie fan who conjures her spirit decades after her death. I’ve always loved cinema, and especially when I was young, I almost felt as if it could be entirely possible for the world of film to bleed over into reality, the concept of life-imitating-art in a very tangible way. It took several years for me to work out how to write it, but when I finally figured out the through-line, I knew it had to be a centerpiece of the collection. Because so many of my stories are about outsiders and forgotten voices, this story felt very much like a synthesis of all of those elements, a way of reclaiming a lost soul and bringing her into the light where she deserves to shine.

I tinkered with a couple different versions of the title, and when I hit on this, I knew it was the right one. For me, the title is both fantastical but also grounded in reality; it’s about how someone you love can truly stop time and change everything in your particular slice of the universe. Plus—and here’s one of my many idiosyncrasies as a writer and a fan—I’ve always adored story names that are also full sentences; there’s something appealing to me about a title being a complete thought of its own. It’s like it announces itself in no uncertain terms.

HN: We won’t ask you to pick favorites, but which of the stories in your collection was the hardest to write? Which was the easiest?

GK: Fortunately, none of the stories in the collection were too disagreeable; most of them came together with few, if any, battles. If I did have to pick one, “The Lazarus Bride” was probably the hardest to write. It was one of the last stories to be completed for the collection, and it’s also the longest piece in the book. The genesis for the story came from the nexus of Sylvia Plath’s poem, “Lady Lazarus,” and Led Zeppelin’s song, “Tangerine.” I wanted to explore death and rebirth and how those elements play out in relationships. This one scared me a little bit, because I was drawing so directly from some personal experiences, ones that I had sort of tucked away when I was a teenager, knowing that someday I’d return to them. That sounded all well and good in theory, but when I crafted the concept for this story, I realized it was time to deal with those emotions. And suddenly, it wasn’t so straightforward anymore.

On the other hand, the easiest to write was “Through Earth and Sky,” mostly because it was a gift to my husband, and at first, I didn’t even think I would ever send it out for publication. Consequently, I had no pressure or the usual fears of “will this work for this market? Is this even a marketable concept?” It was another very personal piece, since it was loosely based on the life of my husband’s grandmother, but because I was truly writing the story to one person, my focus was razor-sharp, and I wrote the first draft in less than an hour. Compared to most of my stories, which tend to take about a week or two for the first draft to come to fruition, this was so easy and painless that it was almost scary.

HN: Your stories tend to cover a wide range of thematic grounds and settings, from contemporary reality to more fantastical realms. Where do you see your influences? Not only your literary forebears, but who (or what) are your influences/preoccupations/etc. from the larger world?

GK: This isn’t a surprise to anyone who has read my work, but fairy tales and folklore are a huge inspiration to me. I love how there are certain stories replicated throughout different cultures, and I feel like that lends credence to the idea of a collective unconscious, or these primordial stories that we all share. That’s a perfect segue to mention that I have a graduate degree in social psychology, which also sneaks into my work. In particular, I return frequently to Jungian archetypes: the Shadow, the Trickster, and of course, that aforementioned collective unconscious. I love how surreal and liminal so much of Carl Jung’s work was; I like to think of my own writing as exploring those same strange places.

In terms of specific literary influences, I always cite Shirley Jackson and Ray Bradbury. Those are two of my biggest. But I’m also a huge fan of Sherman Alexie, Tennessee Williams, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Kate Chopin, Sylvia Plath (and the list goes on and on). While speculative fiction reading is a must for all speculative writers, I’ve learned a tremendous amount about craft from other genres as well.

Other influences on my fiction are unexplained disappearances (Roanoke Colony totally unnerved me as a kid), relationships about sisters (particularly strange since I’m an only child), and body horror. That last one worms its way into so much of my work. Human beings are comparatively limited in our bodies—we can’t run fast, we can’t fly, we can’t even survive the elements all that well—and the notion of transforming into something else, something that might even be better, is something that always intrigues me. And there are so many different ways to alter a body in fiction that the possibilities are utterly endless.

HN: In addition to writing fiction, you also run a fully fleshed-out blog—the aptly titled www.gwendolynkiste.com—where you provide all sorts of information, including markets seeking fiction submissions and interviews with other authors. Although you’re currently our interviewee, if you put on your interviewer hat, what question were you hoping we would ask? What question were you hoping we wouldn’t ask?

GK: It’s funny, because you hit on something with the second question: I was hoping that you would ask about the title story. Because it’s original to the collection, I haven’t had a chance to discuss that one as much as reprints like “All the Red Apples Have Withered to Gray” or “Ten Things to Know About the Ten Questions,” which were featured in Shimmer and Nightmare respectively. It’s a little odd, but I feel a kind of obligation to my stories—that if I created them, then I need to get them out there the best that I can. Consequently, it’s nice to talk about the stories that are newer since those ones haven’t been promoted in the past like my other stories.

In terms of what I hoped you wouldn’t ask, since I already mentioned it, “The Lazarus Bride” was derived from a really personal time in my life, and as soon as you say something like that, people want to know a little more, which is completely understandable. I too love to hear the behind-the-scenes anecdotes about how and why something was created; I think everybody does. It’s a bizarre dichotomy of modern life: how often the private becomes public. I’m a big believer in author platforms, so I’m always putting myself out there with blogs and posts on social media, but at the same time, I’m not the person who gives someone my life story the first time you meet me. Heck, you could read all of the stories I’ve written, and you’d still only have a narrow window into who I am. So sometimes, talking quite specifically about inspiration for certain stories can make me a little uneasy.

HN: If you didn’t also answer those questions above, consider this the prompt to do so. No one gets off that easy.

GK: Aww, shucks. Okay then…

When I was writing “The Lazarus Bride,” I was drawing from one of my first—and predictably failed—relationships in high school. That sounds trite, but bear with me. I rarely write about specific relationships, be it family, friendships, or romantic relationships, and in this case, it was pretty much the same. For this story, it was more a certain emotional experience, rather than the particulars of what happened. And since I was a teenager at the time, those emotions were intense to say the least. That’s something I feel that young adult writers never get enough credit for: returning to those highly-charged states of adolescence and making it sound real and not overwrought. That’s a skill very few writers possess. Even with this story, my two characters are adults; I’m only channeling those teenager experiences in a tangential way.

I’m someone who likes to look forward, not back, so it can be hard for me to pull from certain points in my life. With “The Lazarus Bride,” I challenged myself to really dig back to that time, to the feeling of heartbreak and that point where you realize that you can’t salvage the relationship. Even after I was done with the story, I wasn’t sure if it encapsulated that emotion well enough. That’s a concern I think a lot of writers have: the more personal a story is, the harder it is to judge your own work. Fortunately, as we went through the editing process on the collection, Jess requested to move “The Lazarus Bride” to the last story because she thought it was the strongest piece in the book. That was definitely a moment that made me feel like I’d accomplished exactly what I set out to do with that story.

HN: Now, an easier question or two: What piece of writing advice would you give to our readers who are also writers? What was the best piece—or the worst piece—of writing advice you’ve been given?

GK: The best advice I’ve ever heard is also the simplest: keep going. Being an artist of any kind is not the easiest path. There will be so many slow times, there will be so much rejection, and yes, of course, it’s hard to make a living at it. But if you love it, if you feel that burning need inside you to create, then keep going. I truly believe it’s worth it in the end.

On a related note, one of the worst pieces of advice is the idea that if you aren’t absolutely sure all the time that writing is for you, then you don’t want it bad enough. Everybody has moments when it’s hard and when you’re not sure how to move forward as an artist, so I bristle at any advice that doesn’t acknowledge that. There’s so much rejection, and that can wear on you. It’s okay to feel discouraged and even to take a break now and then. But ultimately, you should keep going. The world needs good stories. The world needs honest stories. And if that’s what you want to create as a writer, then keep going. We need your voice in this world.

HN: Finally, what’s on the horizon? Not just what’s coming out next, but also what ideas are you playing with that maybe haven’t been worked out yet—can you give us both something concrete and something abstract to anticipate?

GK: As always, I’ve been busy scouring fairy tales and folktales for inspiration. Recently, I was digging deeper into my Czech heritage and came across the legend of Morana, a female spirit of winter whose effigy is gleefully drowned by local children each spring to usher in warmer weather. If that’s not rife with disturbing horror potential, I don’t know what is.

I’m also keen on the idea of doing more period pieces, especially based in the early to mid-twentieth century. When I was young, I would spend vast amounts of my free time researching different eras in the last century, so it would definitely be fulfilling to fold some of that knowledge into my fiction. That being said, it can be a little daunting to write period-specific stories; I’m always afraid that I’ll get the smaller details wrong somehow. But that probably means I need to push myself to go for it even more. It’s a bit of a conundrum: for horror writers, fear is a vital component for your work, but absolutely not something that should ever hold you back.

More broadly, I really enjoy challenging myself to find new ways of telling a story. I’m always looking for new formats or different points of view that I haven’t incorporated into my fiction before. I’m shopping a horror story right now that’s told through photographic exhibits in a museum. Anytime I can push myself down a new avenue, I always say “Why not?” Even if something doesn’t work, I figure it’s better to fail spectacularly by trying something new than to fail dully with the same-old tropes.

As for concrete plans, I’m in various stages on several longer projects now—including a couple novels and a couple novellas—so I’m cautiously optimistic to see how my style hopefully evolves over the coming year or two. I can’t see myself ever leaving short fiction—I love it far too much—but it will be so much fun to see what’s in store for longer fiction. That’s how I try to think of a writing career: as this fun and crazy ride. I just hope that readers will be eager to come along for the adventure.

BACKGROUND

Bio: Gwendolyn Kiste is a speculative fiction author based in Pennsylvania. Her work has appeared in Nightmare, Shimmer, Interzone, Three-Lobed Burning Eye, and LampLight, as well as Flame Tree Publishing’s Chilling Horror Short Stories, among others. A native of Ohio, she currently dwells on an abandoned horse farm outside of Pittsburgh with her husband, two cats, and not nearly enough ghosts.

Website: gwendolynkiste.com

Facebook: facebook.com/gwendolynkiste

Twitter: twitter.com/GwendolynKiste

Pre-order And Her Smile Will Untether the Universe, available April 14th from JournalStone.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks