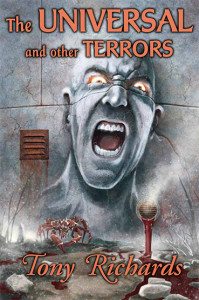

Tony Richards

Dark Renaissance Books, 2013

Trade paperback

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

The Universal and Other Terrors is a solid collection of unsettling stories, well presented, and highlighted by appropriately atmospheric artwork by M. Wayne Miller. The dozen stories range from clear renditions of horror to subtle evocations that allow readers to extend and complete the narratives for themselves.

The headnote story, The Universal, essentially sets the criteria for the remaining tales. Well into the narrative, the key character discovers a notebook left behind by a scientist in a long-abandoned testing center. Among intriguing equations and ominous sketches, he finds the following: “This is generally acknowledged to be one of the great Universal Laws. Events that are impossible are never allowed to happen within our sphere of existence. If that were not the case, then reality would be under constant threat of breaking up in places or even collapsing entirely.”

Clear enough, and reasonable.

Then follows this:

Words like “law” and “allowed,” however, imply intent, a will, a guiding force. A creator. And, being a purely scientific man, I cannot countenance that. But if there is no guiding hand, no actual law, then this characteristic of our everyday existence—this absolute forbidding of impossible events—has to be produced by something physical and real. Perhaps it is a special kind of energy, or matter on the sub-atomic scale, brother to the quark.

It must exist. There is no other explanation. There has to be some actual element surrounding us that binds the fabric of reality together. I call it “The Universal.” And if I can find it, isolate it, maybe it can be altered somehow, to our greater benefit. Just think what we could manage if the plain impossible could be achieved.

I quote these passages at length, not because any of the subsequent stories are precisely sequels to “The Universal,” but rather because in its own way, each explores the possibility of the impossible intruding into everyday life, not through design or scientific manipulation of reality but through…well, the actual mechanisms vary with each story and are subsets of the meanings of the stories.

In “The Universal,” evidences of tampering are small, almost unnoticeable, relegated to a small, seemingly neglected building on the outskirts of a perfectly normal seacoast town. Little happens in the story…except that the narrator sees things that cannot be. And they are slowly expanding.

“Aegea” is largely a story of perception. The central character, Matt, on the final leg of a Mediterranean tour, comes upon a secluded beach, isolated, invisible from the roadway. The only signs of life are the sunbathers, each facing in the same direction, each wearing the same swimwear, a pair of dark blue trunks. Even the woman Matt notices is wearing only trunks. And each wears the same style of dark sunglasses. Aware of a certain oddity about the beach and the bathers, he enters the sea, swimming out far enough that his feet no longer touch bottom. Then he turns toward the beach…and just how odd—how impossible—things there truly are.

“The Visitors in Marvell Wood” concentrates on the ‘little people,’ on faeries, on the perilous interface between childhood and adulthood, and on the consequences when something impossible occurs to alter that interface.

“Covered Mirrors” focuses on traditions—in this case the tradition that, following a death in the household, all mirrors must be covered for a period of mourning. Though young Jody does not quite understand the rationale for doing so, he does know that the tradition causes a breach between his mother, who does not believe in such things, and his father, who does. But eventually, he realizes that there are consequences—impossible consequences—to looking beneath the shroud.

In “The Crows,” nothing horrific seems to happen. Howard Danwell’s wife, Marjorie, draws his attention to a few crows in the garden. Then he returns his gaze to the evening paper with its news of increased glacial melt and out-of-control events in the Middle East. A short while later, a neighbor’s dog is killed by a passing car…and he notices more crows. Life happens, most of it dark, some of it deadly. And there are more crows. And more. And more.

“By a Dark Canal” is perhaps the most intriguing story in that it serves as an ‘unofficial’ prequel to one of the most famous horror novels of all time, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The first pages introduce a stridently atheistic, profoundly opinionated, highly sexually-charged, incomparably brilliant medical student by the name of…Abraham Van Helsing. Believing that the continued health and sanity of a grown man depend upon his going “through the motions of breeding” at least weekly, he heads for an oft-visited part of the city along the edge of a pitch-black canal, where he meets a lady of the evening whose revelations transform him and everything he believed possible.

“Sense” demonstrates how gradually yet inevitably the impossible-to-contemplate becomes not only possible but everyday reality. It is essentially a horror story-version of Martin Niemöller’s famous poem:

First they came for the communists,

and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a communist.

Then they came for the socialists,

and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists,

and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a trade unionist.

Then they came for me,

and there was no one left to speak for me.

It demonstrates through fiction the inevitable encroachment on human rights and liberties—even human life—when small exceptions are made to standards of decency and humanity.

The final story, “A Town Called Youngesville,” is a bit of Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, cross-fertilized with several classic episodes of The Twilight Zone, and just a hint of Levin’s The Stepford Wives. Youngesville is a perfect planned community in Nevada; its newest family, Frank and Joannie, are at first relieved to have escaped the smog and violence of Los Angeles. They have a beautiful new home, they are surrounded by more beautiful new homes, their neighbors are beautiful young people, and there seem to be jobs for everyone. In the center of Joungesville stands its crowning glory, a construct called “New Hope,” a futuristic statue designed by a Nobel Prize winning physicist and constructed by a local artist as a work-in-progress.

Yet…yet several things about Joungesville do not seem quite right to Frank. And he is determined to find out what is going on. To do so he enlists his younger brother, still living in L.A., to find out what he can about the physicist, the artist, and some of the townspeople. His brother does…and that night, someone tries to kill him. A novella, the story allows for development of multiple strands of the story, all leading to the final moments of confrontation, understanding, and—for Frank at least—unutterable horror as the impossible imposes itself upon what had seemed an unexceptionable if not admirable everyday reality.

And the reader is back at the beginning, back at “The Universal,” having been led through twelve variations on the basic premise: if someone or something begins to unravel reality, what horrors might be released.

I’ve not mentioned every story although each deserves it. It is simply that they are all strong, well-written and well-conceived, turning everyday elements on their heads and creating darkness, distress, and horror. Throughout, Richards demonstrates his skill at storytelling, no matter how diverse the stories might be.

Recommended.