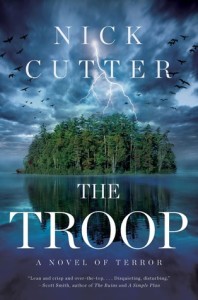

Nick Cutter (pseud.)

Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster, January 2014

Trade paperback, 359 pp., ARC (pre-publication review)

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Within the first few pages of Nick Cutter’s novel The Troop, one is reminded of several crucial realities about camping.

First: Never go camping at an isolated cabin.

Second: Never go camping at an isolated cabin on an isolated island in the ocean, twenty-five miles from the mainland.

Third: If you do go camping at an isolated cabin on an isolated island in the ocean, twenty-five miles from the mainland, never let your transportation drop you off and promise to return a day or two later.

Fourth: If you do go camping at an isolated cabin on an isolated island in the ocean, twenty-five miles from the mainland, and let your transportation drop you off and promise to return a day or two later, never include a sociopath in your group.

Unfortunately Scoutmaster Tim Riggs and five of his fourteen-year-old charges ignore these basic rules for survival…and most of them die. Not just die, but die horribly, painfully, and graphically.

The plot of The Troop is direct enough. The five Scouts and their Scoutmaster are taken to Falstaff Island, just off the coast of Prince Edward Island. The first night, while the boys are sleeping, Scoutmaster Tim encounters a stranger—an almost incoherent, ragged man so frighteningly thin as to be more skeleton than flesh. Shortly thereafter, the stranger dies.

Of what? Well, that is the core of the story. Cutter almost immediately lets us know the superficial cause of death; the more complex version—and the essence of horror throughout— only gradually appears as secondary passages interrupt the primary narrative, giving us critical information that most of the main characters never fully receive.

That is the basic situation as the story unfolds. Something devastating has happened; the boys see only the final result and wait confidently for their ride to return them to home, to safety, to the adult world where children are protected. But the appointed time passes, and no boat. No prospect of getting off the island. And now the boys begin dying.

Cutter does a fine job in populating his novel with believable types that simultaneously become equally believable individuals: the jock, first to impose his will upon others, first to confront danger; the loner, a member of the troop in name only; the fat boy everyone picks on, who finds solace in knowledge and in his superior intelligence; the best friends whose lives reach that inevitable moment when, approaching the cusp of adulthood and caught in the web of an almost unfathomable danger, they irrevocably diverge; and the closet sociopath, who discovers a unique opportunity to feed his deepest needs.

The Troop follows a heritage initiated by two key novels.

The first is William Golding’s 1954 masterwork, Lord of the Flies. The settings are, of course, similar—two highly structured groups of boys isolated on an island, struggling to bring order out of chaos. And in both, the adult world is ultimately responsible both for their plight and for their presuppositions, their core beliefs that in the end make survival difficult if not impossible. In Lord of the Flies, the plane crash is somehow related to a vague war that never quite surfaces as an underlying cause but that is present nonetheless. In The Troop, the Scouts’ situation is caused by…well, without going into too great detail, it is similarly caused by the adults’ preoccupation with warfare.

The second is Stephen King’s masterpiece—in the old sense of something that demonstrates proficiency at one’s chosen art—the 1979 novel, Carrie. Little of the earlier novel’s plot appears in The Troop, but the overriding structure owes much to King’s explorations, intercutting third-person narratives, concentrating on the various characters in turn, with moments of reportorial detachment that distance themselves from the immediacy of the horrors the boys experience, thus further defining them and intensifying them.

Never slavishly imitative, The Troop builds on these and other seminal horror novels (Thinner, anyone?) while remaining uniquely its own story. It is part survival tale, pitting fourteen-year-olds against an unremittingly hostile nature. And it is part monster tale, as the boy’s chances of survival are radically narrowed by the presence on the island of something out of nature, something constructed, for the purpose of killing.

And, at first at least, they seem prepared for the first while totally ignorant of the second.

In all, The Troop is a well-paced, solidly written piece of suspenseful horror, frighteningly graphic in its images, unremitting in its stripping away of the human masks we all wear, devastating in its indictment of the adults who are supposed to nurture children, and unyielding in its insistence that readers continue reading—abomination piling upon abomination—until the final page and the final secrets.

Watch for it in January, 2014—it is well worth the wait.