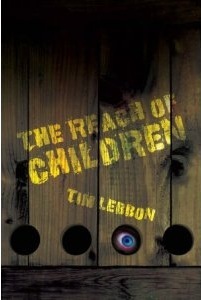

Tim Lebbon

Dreaming in Fire, March 2014

eBook, $2.99

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

The Reach of Children is a precious oddity. It is a ghost story that may or may not have a ghost—perhaps the best kind, since it leaves it up to readers to determine how the story will end. It is a horror story without a true horror—also in some senses the best kind, since it provides moments of terror, of fright, of consternation, that gain in power from their connections with the readers’ world and the readers’ experiences. It is a coming-of-age story about a child, too young yet for the phrase to apply directly, yet one who in many ways outstrips the adults around him in dealing with life…and death.

It is a meditation on death and its accompanying horrors: loss, grief, emptiness, sadness, isolation, alienation. Yet it also moves beyond those into memory, affirmation, reconciliation, and—not painlessness—but the acceptance of pain.

The plot is simple. Ten-year-old Daniel Powell’s mother has just died; the story opens with his father coming into his room in the middle of the night to tell him…but somehow he already knows. The following pages shift between Daniel’s increasing estrangement from those around him, the adults who move into and out of his life during the ensuing weeks as well as his classmates and friends at school; and his growing awareness that there is something deeply wrong with his father. As the days pass, Daniel’s father seems to disappear more and more into a false oblivion provided by beer and pills, until what was once a solidity in Daniel’s life nearly dissolves. On the positive side, his father’s best friend, Gary, provides a kind of constant for Daniel as his life draws to the verge of shattering. On the negative—and it is a huge negative indeed—Daniel’s father is keeping something secret, something hidden in a rough-hewn box beneath his bed, padlocked away from the world.

To arrive at any kind of peace, Daniel must penetrate that secret…to save himself and his father.

I read The Reach of Children in a single sitting. It is not a difficult read but it is a complex one, simultaneously threatening and uplifting. It does little except explore Daniel’s inner life as he deals with everyday-seeming events in the outside world: surviving the emotional upheavals of his first days at school following his mother’s funeral; playing in the woods with his best friend; dealing with his father’s deepening alienation; and—always and forever—coping as best he can with the horrifying fact of his mother’s death. Yet such a flat summary belittles the depths of storytelling contained within the simplest actions and the resonation they have for Daniel.

When I finished the story, my first thought—beyond “wow!”—was that this piece reminded me, in treatment and in effect rather than in storyline, of one of Stephen King’s finest short stories, “Do the Dead Sing?” (also and paradoxically published as “The Reach). King’s story is also a gentle meditation on loss, on change, this time told from the perspective of age rather than from youth. But the effect was much the same. For the brief duration of the story, I was caught firmly within a world of uncertainty and pain; by the end, those feelings had transmuted into something powerful and redemptive.

In the final words of the story (no true spoiler here), “And the future would begin.”