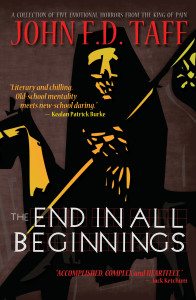

John F.D. Taff

Grey Matter Press, 2014

Trade paperback, 320 pp.

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Just under half a century ago, I discovered a personal “tell” that let me know when a performance had touched me deeply. Several friends, all of us college freshmen, had just watched Peter O’Toole’s performance in Lord Jim. As we walked back to the dorm, they chatted—as freshmen tend to do—about art direction, nuances of performance and location shots, subtlety of imagery, and complexity of symbolism…everything, indeed, except the story.

Normally, I would have joined them; any number of late-night conversations intent on solving the problems of the universe had convinced me that I could hold my own with them. But this time there was something different, something odd.

I found that I couldn’t talk about the film.

The story had resonated so strongly with me that to open my mouth and break what had become a powerful and meaningful silence was simply impossible.

That experience—with minor variations—has recurred many times since. When I finished reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings for the first time. When I read John Milton’s Paradise Lost in one sitting as an undergraduate; I was supposed to be studying for a final exam but the story captured me and suddenly I was turning the last page of Book XII and wishing there were more. Listening to the final “Prisoners’ Chorus” of Beethoven’s Fidelio at the Hamburg Opera House near the end of my two-year church mission in Germany. When I finished Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbevilles for a graduate course in Victorian literature. When I finished Stephen King’s It, reading a typescript he had sent six months before the novel was published…and, yes, it was roughly the size of a human head.

There have been more examples over the years, some expected and of short duration; some unexpected and sudden, almost paralyzing in the intensity of emotions generated. But all signaling that I have read or seen something that has changed me and my perceptions of the world in important ways.

The last time it happened, I had just finished John F.D. Taff’s collection of horror novellas, The End in All Beginnings.

By that, I do not mean to suggest that the book should be read as a masterwork of world literature; that would place too much weight on a series of relatively short tales in what many might consider an ephemeral sub-genre…if they consider horror literature at all. And it would be to wrench Taff’s intention in ways that would be unfair to him and to his stories.

No, my experience—my period of quiet, of inability to talk about what I had read (in fact, I am writing this two weeks later)—stemmed from the fact that he elected to tell stories that would matter, that would grab imaginations and direct them to new and unanticipated places.

The first, “What Becomes God,” uses a nicely ambiguous phrase to introduce what initially seems a perfectly toned discussion of life, death, love, loss, and God. Every word contributes to a nostalgic re-creation of childhood lost, of a boy coming to grips with disease and death for the first time. Every word, that is, until the key phrase—“It was the blood”—when everything changes…and what comes after is awesomely horrific (using awesome in its deeper senses) as the boy comes face to face with the consequences of his desires and his prayers.

“Object Permanence” begins in the darkness of nightmare, in much the same universe as “What Becomes God” ended. In this case, a man in an insane asylum endures visions and hallucinations that, had they been real, would have driven anyone beyond the limits of sanity. Chris Stadler’s story embraces horror when he realizes that in the most fundamental ways, his hallucinations had been real, and that the only way to understand them and restore his shattered memories is to confront his home town, the ancient house in which he had been raised, and his great-aunt Olivia, the source of an evil that may be too powerful to stop.

“Love in the Time of Zombies” is an oddity among zombie tales in that one of the three main characters is a zombie—usually such tales use the walking dead merely as set dressing that takes an occasional foray into destruction. The landscape is perfect: a small, isolated Midwestern town a hundred miles from nowhere, in which Durand Evars discovers that everyone is either dead or a zombie. Almost. The sole exception is Scott Gibbons, whose preoccupation turns out to be gaming. The two hole up in a huge warehouse-type store, with all of the provisions and protections they could hope for. Time passes…until Evars sees her, a beautiful young woman—unfortunately a zombie—with whom he immediately forms a distinctly one-sided attraction. And equally unfortunately, he is not the only one to do so.

“The Long, Long Breakdown” is set in the upper stories of a South Florida high-rise some fifteen years after the climate has shifted and drowned much of the world. Florida was the first to go, and since then the narrator and his seventeen-year-old daughter have lived within a circle defined by his ability to row their small boat safely from one ruin to another, collecting medicines, supplies, and most importantly books. He is content to remain as they are, essentially looking backward and remembering; he does not realize that his daughter has no memories of the other world and is instead beginning to look forward, into a future he cannot imagine. They are at an equilibrium in their desires…until she discovers a telescope and, through its lenses, sees the unimaginable. How each handles the revelation is the crux of the story, one of the most powerful in the collection in its simplicity and in it systematic ‘breakdown’ of old beliefs and fears in the face of the new.

“Visitation” crosses genre boundaries several times. It begins as science fiction, as Fenlan Daulk is notified that he has won the annual Galactic Lottery—a two-week stay on Visitation, long known as the most haunted planet in the cosmos. Having just lost his wife, he is stunned at the possibility of seeing her again, and crushed by his knowledge that such things as ghosts cannot exist. Or can they? As his visit progresses, and his story moves into the realm of ghost story and fantasy (or does it?), he comes to discover closely guarded secrets that pass far beyond the temporal grief of one man and encompass the existence of life beyond anything he could have imagined.

In each of the five tales, Taff provides carefully nuanced, skillfully balanced components—storytelling, nostalgia, horror, human emotion—to work from beginnings to ultimate ends…sometimes death, sometimes things far worse, and sometimes something magnificent.