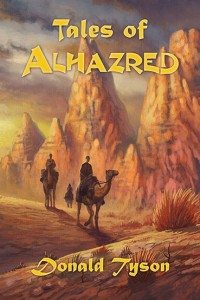

Donald Tyson

Dark Renaissance Books

September 24, 2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

In the distant past (it now seems so long ago that dinosaurs might have still ruled the Earth), there was a popular television series called Have Gun—Will Travel. The black-and-white Western ran from 1957 (okay, so I was ten when it debuted) until 1963, with writers that included Bruce Geller, Irving Wallace, and Gene Roddenberry, subsequently famous for creating the first incarnation of the Star Trek empire.

Each half-hour episode starred an excellent but atypical, gruff-voiced, craggy-faced, decidedly un-handsome actor, Richard Boone, as Paladin, a gunslinger-for-hire in the post-Civil War era. From there, stories might take viewers anywhere in the still-exotic landscape of television’s early conceptions of the Old West. There would be villains and dastardly deeds, to be sure, and Paladin—true to the etymology of his name, which refers to one of the twelve warrior-knights of Charlemagne—could use violence when necessary but preferred the more gentlemanly attributes of intellect, observation, and understanding.

The series became standard family viewing in our home. I remember it as interesting and fun, mostly because of the oddities surrounding the “man in black” with the “fast gun for hire”—a “soldier of fortune” willing to donate his services to those in need. For half an hour, we could count on seeing familiar faces in unfamiliar places, watching ingenious plans for evil unraveled by equally ingenious plans for good, and finally leaving that landscape, secure in the knowledge that we would revisit the following week.

What has this to do with Donald Tyson’s Tales of Alhazred?

Put simply, Tyson has transformed one of the most formidable, mysterious, and fearsome human characters in the Lovecraft mythos—the “mad Arab Abdul Alhazred”—into the star of a short-story series that provides much of the same species of entertainment as did Have Gun—Will Travel.

There is the unlikely hero, Abdul Alhazred, human with the heart and soul of a ghoul and an internal djinn who surfaces when needed. Once a handsome luminary at the court of an eighth-century Yemeni ruler, he is now hideously scarred as punishment for misplaced amorous advances. A necromancer of enormous reputation (although he admits that much of that reputation is due not to his own knowledge but that of one of his companion, Marlata) he will sell his services…or give them, depending upon the situation. He travels through generalized landscapes—vast deserts, ancient and partially ruined cities, shadowy necropolises, rough mountain redoubts—usually accompanied by the same cast of characters. He fights evil in all of its physical manifestations, most prominently djinni and ghouls but often amorphous or insectile or tentacled creatures from other spheres (literally in one story), magicians and other necromancers, and simply evil, venal humans.

Oh, and along the way he encounters Lovecraftian Old Ones.

That is where Tales of Alhazred falters for me as reader.

The stories—even those that conjure Yog-Sothoth and carefully avoid revealing the name Nyarlathotep—lack the sense of the cosmic, of the other, of the outré in its original sense of ‘beyond all barriers.’ The actions are human-based, earth-based, even when they incorporate a gigantic maggot-like monster worshipped as a god or an enigmatic black sphere that opens onto another world, which remains largely unexplored and unexplained. There is a safeness to the stories, a feeling akin to watching the closing credits of an enjoyable television episode, relaxing slightly that the hero has escaped again (although that was really not in doubt), and looking forward to much of the same next week. For stories about the early life of the author of the most notorious book in creation, the Necronomicon, these seem remarkably tame, with little to hint of horrors and madness.

This is not to say that the stories are uninteresting. They are solid, well told, with sufficient twists and turns to keep the momentum going to the final page. And they are accompanied by color and black-and-white illustrations by Frank Wells, each aptly capturing a key moment and making it visual. But in the end, they fall uncomfortably into a niche somewhere between the Tales of the Arabian Nights and revelations of Lovecraftian Horrors, partaking of both but perhaps not enough of either.