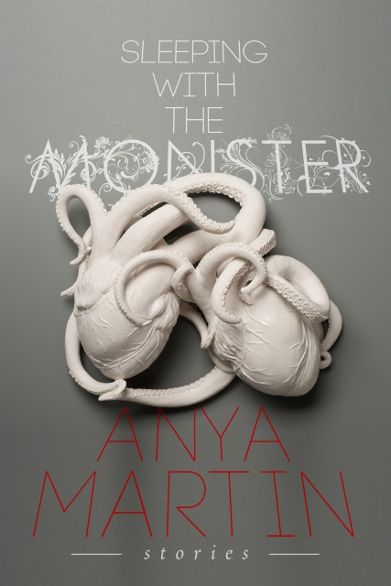

Sleeping with the Monster

Anya Martin

Lethe Press

October, 2018

Reviewed by Gordon B. White

Anya Martin’s debut collection, Sleeping with the Monster, collects a dozen tales of women and monsters, although that’s not to say that the lines between them are always clear. Through Martin’s astute configurations of womanhood and the Weird, distinctions shift and blur, gifting readers with guideposts (but no single path) to confronting the Weirdness of modern life. While there are enough different outward variations in Martin’s stories for any reader to find a toehold, there is a shared DNA in the author’s piercing insights that makes all of these stories vital.

Sleeping with the Monster’s stories are fiercely concerned with contemporary womanhood, but they do much more than merely examine the pressures of society’s demands and expectations. Martin also turns her attention to dissecting these characters’ expectations of themselves and, in turn, their explorations of themselves. Without idolizing or vilifying, Martin looks at the Weirdness of being a woman in the modern world through a dozen different frames. Beginning with the girlhood diaries of “A Girl and Her Dog” where the expectation of women’s sacrifice is first ingrained, through the ideological and familial expectations of the marriage at the heart of “The Un-Bride, or No Gods and Marxists,” and culminating in a house haunted by the (almost) widowhood of the final novelette “Grass,” Martin uses her stories’ speculative elements to chart the strangeness of becoming and being a woman.

Stylistically, although the edges of these stories are in the Weird, they are wonderfully grounded by their sense of real-world time and place. There are a few that feature historical persons or events, but even those involving only fictional characters occur in real cities and have cultural touchstones via actual music or films. Even “Jehessimin,” the story that most fully embraces the fantastic, begins in our recognizable reality before traveling to an underworld of Fae and Erls. Given this grounding, it should be no surprise that despite the intrusions by the strange and the supernatural, these stories share a persistent sensibility reflecting a contemporary wariness towards the relationships between women and men, and, through that, between women and the world.

This wariness is not necessarily a weariness, however, since love can exist here. In “The Un-Bride” Elsa Lanchester (the actress of Bride of Frankenstein fame) asks, “Why do men always expect women to love them?”, but in these stories, everyone expects to be loved. It is through Martin’s piercing examinations of the heart in conflict with itself that these women grapple with defining themselves through the lenses of their partners, their responsibilities, and, finally, their own desires. Are duty, desire, or comfort substitutes for love? Is feeling loved the same as being loved? What does a person owe to love, and what does she owe to herself? These are hard questions but Martin’s fiction comes at them again and again, unsatisfied with merely presenting variations on a theme and instead employing new tactics in each story’s attempt to shine at least a partial light.

When an author is willing to take risks to find her voice through different settings and tones, not every reader will have the same reaction to every story. Martin, however, experiments with enough different story forms that there is something here for every preference: Fans of historical Weirdness might like the wild “Un-Bride” or the haunting Post-WWII one-act play “Passage to the Dreamtime,” while those seeking pulpy psychedelia will find their jam in “Resonator Superstar!” or the entheogen-fueled rock and roll of “Sensoria.” Fans of outright fantasy will appreciate the Fae quest narrative of “Jehessimin” or the 1980s-cum-Gothic gargoyle romance “Black Stone Roses….,” but aficionados of contemporary, domestic horror will find no finer pleasures than “Boisea trivittata,” “Window,” and “The Prince of Lyghes.” Whatever genre trappings a reader may prefer, there is something here for them; however, while the bodies may change, the hearts of these stories are more similar than they might first appear. As such, the variety of stories in Sleeping with the Monster should be seen as entry points, not solitary morsels.

While still under the caveat regarding reader tastes, for this reviewer, Sleeping with the Monster works best when it works in the domestic Weird. The triptych of “Boisea trivittata,” “Window,” and “The Prince of Lyghes” tackle modern anxieties through the lenses of isolation, appeasement, and revolt by employing varying levels of surreality in the speculative element. Furthermore, the collection’s capstone is the novelette “Grass,” which handles all of these in succession (as well as adds a tinge of the erotic) and stands as fitting encapsulation of many of Martin’s concerns throughout this book. There is an understated vividness and vitality to these stories that is sometimes harder to recognize the more bombastically entertaining tales, but when Martin hones in on the simple pleasures, pains, and irritations of modern life, her keen insight is most deeply felt.

While each story in Sleeping with the Monster is enjoyable on its own, together they document a necessary grappling with the Weirdness of our world and the roles that women are expected to play. Throughout these twelve stories, Anya Martin faces this challenge with hard-won insight and grace again and again, securing her place as an important voice in contemporary Weird fiction.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks