Edited by Aaron J. French

JournalStone

December, 2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Much has been said recently about Howard Phillips Lovecraft.

A fair amount of it has been stridently negative.

He has been ridiculed for his facial features and disparaged for beliefs inculcated in him as an adolescent, although they became less strident as he matured.

His style has been castigated as “lugubrious” and “turgid”—both, curiously enough, words he would have appreciated for themselves. His stories sometimes seem to have little or no plot; descriptive, atmospheric darkness or evocative weirdness suffices instead of actions and resolutions. They likewise often have little in the way of fully-rounded characters; and when they do, the characters frequently seem rather like each other, which is understandable since most of them derive from “the ancient, lonely farmhouses of backwoods New England; for there the dark elements of strength, solitude, grotesqueness, and ignorance combine to form the perfection of the hideous.” (“The Picture in the House,” 1921).

On the other side, he has been rightly acclaimed as the originator of a particular branch of horror literature that has endured for nearly a century and that, if anything, is as prevalent today as it was half a century or more ago. Few authors have been honored with an eponym-creating suffix: Chaucerian, Shakespearean, Miltonic, Swiftian, Byronic, Dickensian, Faulknerian, Heinleinian are among them. Each word defines a specific sub-genre, a kind, with a well-defined sense of style; characteristic vocabulary; narrative structures, both macro- and micro-; themes, approaches, and contents. Simply to say the word conjures a complete vision of a clear-cut sort.

Among horror writers, Lovecraft is the premier example. Lovecraftian horror or Lovecraftian supernatural horror conjures a vision uniquely linked to his name and diligently expanded upon by generations of fans, followers, and imitators.

In part, his influence stems from those elements some readers and critics choose to disparage. Yes, his style can seem overblown and pretentious, especially for readers conditioned to post-Hemingway curtness and directness; readers of his own times, perhaps more familiar with the conventions of eighteenth-century prose than we are, would have responded more positively to his elegant constructions, his labyrinthine periods, to sentences whose formation are almost as much a contributor to meanings as his words. His vocabulary might be abstruse, but it is always accurate. And his landscapes at times become virtual characters. To take an example, here is the second paragraph from “The Picture in the House”:

Most horrible of all sights are the little unpainted wooden houses remote from travelled ways, usually squatted upon some damp, grassy slope or leaning against some gigantic outcropping of rock. Two hundred years and more they have leaned or squatted there, while the vines have crawled and the trees have swelled and spread. They are almost hidden now in lawless luxuriances of green and guardian shrouds of shadow; but the small-paned windows still stare shockingly, as if blinking through a lethal stupor which wards off madness by dulling the memory of unutterable things.

The movement from “Most horrible of all sights” to “the memory of unutterable things” twists and turns through three complex sentences, carrying readers through time and space and sanity.

Beyond this, though, Lovecraft achieved something few writers have attempted. He created a cosmos inhabited by beings—mortal and immortal—so far beyond humanity as to be almost incomprehensible. For lack of a better term, the most enduring of them touch upon being gods; and the most horrifying neither care about humans nor are hostile to them, but are absolutely and utterly, coldly and completely indifferent to what happens on this miniscule planet.

Perhaps more than anything this cosmicism explains Lovecraft’s perennial influence. During his lifetime, friends and fellow-writers helped themselves to his universe, inventing whole pantheons of lesser gods to bolster his originals. The tendency to borrow and to augment continued until his death in 1937 and beyond, manifesting itself most recently, perhaps, in characters appearing in role-playing games.

Underlying all of the accretions, however, and warranting their existence, are Lovecraft’s gods. Some are so well known that their names come with ready-made mythologies: Great Cthulhu, the most prominent, the most expansive, the most hideous of monsters; Yog-Sothoth, almost reborn into this world through his grotesque son in “The Dunwich Horror”: the “far Daemon Sultan” Azathoth; and Nyarlathotep, the “crawling chaos.” Others are less familiar but equally capable of stimulating nightmares and beneath them writhe scores of additions by August Derleth, Clark Ashton Smith, Abraham Merritt, Brian Lumley, and dozens more.

Still, there is the core.

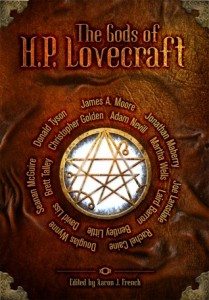

That core is the focus of The Gods of H.P. Lovecraft, edited by Aaron J. French and featuring twelve stories exploring possibilities implicit in the Cosmic Mythos. The volume is a paean not only to the imaginations of the writers involved—which are as wide-ranging as they are unpredictable—but to the richness of Lovecraft’s initial creations. Each story takes as its starting point with one of Lovecraft’s cosmic entities, however precisely or vaguely defined in his stories, and develops it into something new, something integrally tied to modern audiences, something that transcends imitation or mere replication to move farther into the unknown.

Some are set in distinctly Lovecraftian landscapes, as is Joe R. Lansdale’s “In the Mad Mountains,” a tale of the Elder Things set in a landscape desolation, of ice and snow, of star-head things and tentacular monsters. Although a later story, it expresses one of the themes implicit in the Mythos: As a character is swept into the mouth of a resurgent creature, gigantic and impossible, “‘Why?’ she yelled to the wind and water. ‘I am nothing. I’m not even an appetizer’”—the nothingness, the less-than-nothingness—of humanity in the face of the Old Ones.

Others start in more familiar settings and from there trespass dangerous borders that are better left uncrossed: Brett Talley’s “The Apotheosis of a Rodeo Clown,” which begins in California’s Owens Valley and from there follows its circuitous trail into madness and into the realm of the toad-like Tsathoggua. Or Douglas Wynne’s “Rattled,” which moves across America toward the Mojave Desert, the Valley of Fire State Park, and the resolution to a mysterious death years before, and a confrontation with the serpent-god Yig.

In between are stories that move seamlessly from one kind of tradition to another. Jonathan Maberry’s story of the Night Gaunts, “Dream a Little Dream with Me,” also stars a werewolf-detective, Nazi treasure-hunters from the Thule Society, an Ogre, and a secret entrance to Lovecraft’s Dreamlands. Bentley Little’s “Petohtalrayn” begins by linking evidences of a mysterious Dark Man with historical disappearances, Mayan myth, Christian missionary journals, and lost tribes.

Perhaps the most evocative of the stories is Adam LG Nevill’s “Call the Name,” a stark creation of an Earth nearing annihilation, as the last of four generations of women, all plagued by premonitions and insanity, must watch as her worst dreams develop around her…as humanity inadvertently prepares the way for the return to the surface of the submerged citadel R’lyeh and its dreaming god, dead Cthulhu.

Rounding out the volume are: Martha Wells’s “The Dark Gates” and Yog-Sothoth; Laird Barron’s nightmarish tale of time-travel, “We Smoke the Northern Lights,” and Azathoth; David Liss’s “The Doors that Never Close and the Doors that are Always Open,” and Shub-Niggurath; Christopher Golden and James A. Moore’s “In Their Presence” and the Mi-go, Rachel Caine’s “A Dying of the Light” and the Great Race of Yin; and Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Beneath the Waves” and the Deep Ones.

It is a tribute to the power of Lovecraft’s cosmos and the fertile imaginations of the storytellers that none of the tales sound alike, none of them are cookie-cutter representations of conventional expectations of things-Lovecraftian. Each develops its own tone, its own way of interpreting creatures that have—in literary terms, at least—taken on lives of their own over the last near-century.

In addition, the volume becomes a compendium of Lovecraft’s Others through commentary on the deities by Donald Tyson, several pages at the end of each tale outlining the backgrounds, locations, powers, and attendants of each god. Prefacing each tale is a black-and-white interpretation of the relevant god or, when physical descriptions are too vague, of a key event within the tale.

In all, The Gods of Lovecraft is beautifully produced and beautifully rendered, offering “Searchers after horror” a multitude of “strange, far places” to haunt.