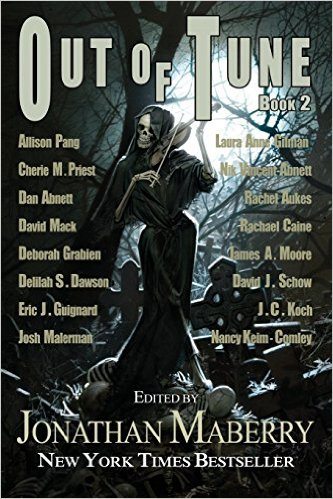

Edited by Jonathan Maberry

JournalStone Publishing

May, 2016

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

When I was first approached about reviewing Jonathan Maberry’s anthology of horror and fantasy tales, Out of Tune, I was a bit wary. Not from worry about the quality of the work; Maberry has an excellent ear for storytelling, and the list of contributors included a number of authors whose tales I have enjoyed—Eric J. Guignard, James A. Moore, David J. Schow, to list only a few of the fifteen masterful writers.

No, I was concerned more by the theme: folk music. I have loved music all of my life…but mostly classical. And because of my deafness I’ve not listened to much of anything for a decade. So the idea of stories based on old folk tunes was intimidating.

Then I flipped through the book, just to get a sense of what it contained. The first things I noted were the eerie B/W illustrations by John Coulthart preceding each tale. Without having read the stories, I was impressed by the evocative nature of the drawings, already being drawn into the mood of the anthology. Next came the commentaries at the end of each story, written by Nancy Keim Comley, giving a brief history of the tunes that inspired the authors, quoting lines when relevant, providing a list of artists who have performed them.

And I found my hesitance dissipating. I recognized several of the songs: “Red River Valley,” “House of the Rising Sun,” and—curiously enough—an old favorite from graduate school, a medieval ballad called “The Twa Corbies.”

Okay, this was beginning to get interesting. But still…so many horror writers seem to use snatches of lyrics—often rock or metal, which I’ve never listened to at all—as a kind of shortcut to characterization, or as chapter headings, leaving me with the sense that I am missing something important by not being able to hum along, as it were.

Maberry answers this final concern in his in his lyrical introduction when he writes:

…on the whole the stories they wrote are independent of the source material. They picked old ballads and songs as inspiration, but none of them sat down to do a straight adaptation. Instead they used some element or feeling within the ballads as a stepping off point. And from there…

Wow.

Magic.

Now that I could understand. So I began reading.

Allison Pang’s “Respawn, Reboot” seems at first about as far from folk music as possible. It is a complex tale of the current generation’s obsession with RPGs and MMOs—with only an occasional touch of banshees and things dark and mysterious. Yet as the story progresses, the two themes draw closer until, in the final paragraphs, they merge into a perfect crescendo of horror, followed by the after-note, which reveals the source poem, W. B. Yeats’ “The Stolen Child.” And the three parts of the story-experience—introductory illustration, the tale itself, and the information about the song/poem that inspired it—combine to create a whole greater than the sum of its parts. A similar fusion works for all of the stories, which creates a great part of the attractiveness of Out of Tune, Book 2.

Cherie M. Priest’s “The Knoxville Girl,” is a close cousin to Ambrose Bierce’s classic horror tale, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” In the space of time it takes a young man to shower—and remove any lingering traces of blood—Priest compresses four generations of women suffering abuse at the hands of the men they have chosen, until the final link in the chain must accept it as inevitable or end it forever.

In “The Beams of the Sun,” Dan Abnett uses “The Bitter Withy” to create an unnerving story of a dead folk singer; his bitter and vicious wife, Marie; and their thirty-three-year-old son, Jason. Biblical echoes emerge gradually in this tale of near-blasphemous lyrics, a lost book of powerful songs, and a collector’s obsession with discovering truth.

David Mack’s “Midnight Rider” returns to the nineteenth century for a formidable story of a wealthy rancher, his only daughter, and the man she has chosen for her husband. It incorporates Old West morality, contemporary concerns about racial equality and justice, and the time-honored horror trope of the dead returning to claim its own.

Delilah S. Dawson’s “Just Another Black Umbrella” is a weirdly entrancing tale of love and loss, centering around a rigidly correct and controlled funeral-home director and a woman who suddenly appears in his life and just as suddenly disappears.

In Eric Guignard’s “The House of the Rising Sun,” opium dreams take on a reality that shatters the dreamer, who returns to the house again and again, desperate to fill gaps in his life but able only to find illusion.

Josh Malerman’s “Who Is Bringing Milk to Me?” captures the ghostly feeling of Conrad Aiken’s “Silent Snow, Secret Snow” in the image of a paralyzed girl whose high point each week is listening to the approach of the milkman, first his footsteps drawing nearer, then his whistle. Aiken’s story ends with madness; Malerman’s, with something much worse.

“A Tale of Three Deaths,” by Rachel Aukes, turns a sordid case of suburban infidelity into a far more threatening story of demonic manipulation and of betrayal for the sake of betrayal; while James A. Moore’s “In the Woods, Somewhere” openly embraces the outré and the eldritch as a hard-bitten retired detective recounts his single experience within the perilous realm of færie.

And so they go.

Illustration, story, commentary—all working together to create fifteen unique experiences in visual and aural darkness, building on generations of murder ballads, poems of the uncanny and the inexplicable, songs of love and loss.

The result is an amalgam of the odd and the unexpected that provides shivers, frissons, and delight.

Recommended.