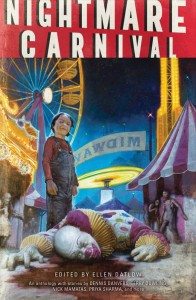

Ellen Datlow, ed.

Dark Horse Press, September 2014

Trade paperback, 383 pp., $19.99

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

The title Nightmare Carnival is both precise and descriptive. The fifteen tales collected in the anthology are nightmares—of the purposeful, literary sort—that, like the smell of circus peanuts, linger in the mind to be replayed again and again. And they are a carnival, with its etymological evocation of flesh, complete with exotic animals fanged and unfanged, ghoulish and ghastly clowns, lithe trapezists seemingly defying death (although death always wins), and an assortment of freaks…whether one applies the term to physical aberrations or psychological ones.

The first story, N. Lee Woods’ “Scapegoats,” is a powerfully horrifying glimpse into the human need to assign blame, even when we are ourselves the cause of whatever has damaged us. In this instance, the scapegoat is an elephant, condemned for doing what any creature—sentient or not—would do…striking back at something that has caused it pain. The initial conflict seems minor, but the consequences, and the need for someone or something to pay, grow with each paragraph, culminating in the first overtly horror-driven scene in the collection, one that is almost too revulsive to bear. And yet, we must; it speaks to and about us.

Priya Sharma’s “The Firebrand” and Dennis Danvers “Swan Song and Then Some” are about kindling passions. They focus on the compelling power of love, even when that love is tied inextricably with death. And they are about the underlying human need to experience vicarious danger, symbolized by the circus/carnival with its juxtaposition of pomp and glitter and color with the ever-present threat (or apparent threat) that wild animals might attack, that a trapeze artist might fall, that someone might actually die while entertaining paying customers. And in the latter tale, Alexandra fulfils that desire in all, singing her “swan song” as she plummets from the tent’s top rigging, holding one impossible, indescribable note as she plunges to the ground, and to her bloody, terrifying death…every night and two times on Sunday.

Nick Mamatas’ “Work, Hook, Shoot, and Rip” and Terry Dowling’s “Corpse Rose” both play with the carnival’s unique jargon. Words that seem pedestrian in the outside world become sinister, threatening, in the world of the carnival, and as characters—and readers—understand more and more about the words used, the darkness beneath the lights reveals itself.

Jeffrey Ford’s “Hubler’s Minions” diminishes the carnival to its smallest possible manifestation: a flea circus. These fleas, however, are not ordinary—nothing presented in Nightmare Carnival is ordinary. They rise from the dust bowls of the 1930s to infect and devour, first animals, then fellow performers. And, if they get their way, all of humanity.

It would be possible to highlight any of the stories in Nightmare Carnival, point out excellences in each. Datlow is a first-rank editor, and her choices ring true throughout. Several stories are told from in third-person present-tense (e.g., “She walks away….”), which I normally find distracting and less effective than past-tense narratives…except that here, there are specific reasons for that choice, pay-offs for readers that validate authors’ decisions and Datlow’s selections. And that comes as near as I can to a negative comment on the anthology. In all, it is strong, with fascinating characters, conflicts, and settings; it is intriguing that the term carnival can be made to mean so many things and incorporate to many varieties of horror…including one bona fide werewolf.

If you have a lingering fear of clowns, perhaps stemming back to reading Stephen King’s IT on a dark and cloudy night; if you are not certain why lions can be so intimidating, even locked in their cages; if you wonder what life must be like for those for whom the anonymity of a carnival back lot is the only choice; if, in a word, you suffer from any form of “carnival nightmares,” don’t let this book pass by.

It’s a killer.