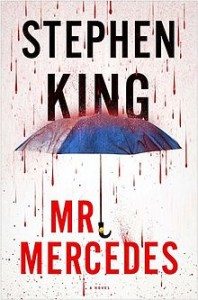

Stephen King

Scribner

June 2014

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Mr. Mercedes is vintage Stephen King of a particular sort—Stephen-King-without-supernatural-monsters. It is indeed a horror story, much as Misery was a horror story, or Gerald’s Game (although that one remains my least favorite of all of his works), Dolores Claiborne, “The Body,” or other tales in which the monsters look like us, act like us, and in fact are us. In this case, the monster is a psychopath determined to destroy as many people as he can in as spectacular a way as possible, yet to everyone around him, he is simply a pleasant, rather nondescript young man, as unthreatening as anyone else.

Opposing him is another of King’s older protagonists, reminiscent in some ways of Ralph Roberts in Insomnia. Hodges is a retired detective, arguably near-suicidal, certainly at odds with himself for having failed to solve several crucial open cases. When he receives a long letter signed “THE MERCEDES KILLER,” he rediscovers his sense of purpose and recommits himself to capturing the serial killer that had eluded him for years.

Mr. Mercedes touches on a number of contemporary themes, including the isolation of individuals in our world and their paradoxical lack of privacy (Mr. Mercedes seems to know a great deal about Hodges personal moments, far more than he has any right to). It looks at the fact that there are killers—either real or potential—among us, waiting for the right moment, the right stimulus, to destroy. It considers the increasing significance of electronic media in our lives—much of the ‘detecting’ in the novel takes place using computer networks. And, as do so many of King’s stories, it depends upon bonds of friendship, even love, forged through common loss, common sacrifice, and common danger.

Beyond being a meticulously developed examination of sanity and insanity, responsibility and ultimate selfishness, the novel is intriguing for several additional reasons. One is that the present-time episodes are told in present tense: “Hodges sits where he is for two minutes, four minutes, six, eight.” Normally this approach bothers me; I am traditional enough to prefer past-tense, third-person narratives. Still, I was halfway through Dolores Claiborne before I realized that that novel was not only technically first-person but a single, uninterrupted monologue told in present time about past events. In Mr. Mercedes, King employs a variation of the device carefully, integrally, differentiating between past and present actions accurately and effectively. After a while, the shifts come to seem natural, actually facilitating the flow of the story.

Another reason is extra-literary but fascinating. I read Mr. Mercedes on my Kindle—which seems appropriate considering the importance of such devices to the story. About three-quarters of the way through, I came upon the following comment, already underlined, with the note that it had been highlighted 603 times by previous readers:

Every religion lies. Every moral precept is a delusion. Even the stars are a mirage. The truth is darkness, and the only thing that matters is making a statement before one enters it. Cutting the skin of the world and leaving a scar. That’s all history is, after all: scar tissue. (324)

Six-hundred-and-three highlights! Reading through the passage, I could imagine seeing it appearing eventually as a meme on Facebook or one of the other social media sites, accompanied by an a suitably Mephistophelian photograph of King, as evidence for the ineffectiveness, if not total uselessness of faith in a science-oriented, objective world. Certainly I’ve seen sufficient other quotations attributed to famous people to evoke the same belief.

There is only one problem with the fact that 603 people apparently felt the comment correct enough and important to highlight it: it is spoke by a madman, a sociopath, a human monster, and therefore does not—in fact cannot, considering King’s other overt statements about God in such works as Needful Things and Desperation—represent King’s beliefs. Context is everything. And some pages later, King writes the following: “Gallison doesn’t reply, and Hodges turns back to the two unlikely associates God—or some whimsical fate—has ordained should be with him tonight” (404). While the sentence suggests ambiguity, this time the context of the novel as a whole indicates that emphasis should fall on the first possibility rather than the latter.

These two rather technical matters aside, Mr. Mercedes proved well worth the read. Considering the ice and snow outside and the hint of chill seeping around the double-glazed window panes as I write, it seems appropriate to conclude by saying that Stephen King’s Mr. Mercedes is both monumental and glacial.

Generally, words such as these are negative, especially when applied to novels, as in “the pacing is glacial,” i.e., events move so slowly that it would be more entertaining to wait until summer and watch the grass grow. In this case, however, I refer more to the physics of glaciation than to apparent movement. Mr. Mercedes at times seems slow, almost as if the plot had come to a halt, but beneath that stillness, events and understands move, imperceptibly perhaps, but with a powerful sense of inevitability and even—perhaps—destiny.

Recommended.