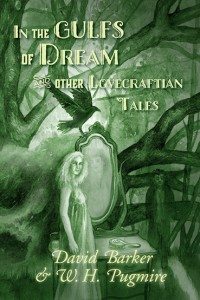

David Barker and W.H. Pugmire

Dark Renaissance Books

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

While at a science fiction/fantasy conference some thirty-five years ago, I picked up a collection of tales by the estimable Gene Wolfe. I had not yet encountered his memorable Book of the New Sun tetralogy, so I must admit to having been drawn to the book primarily through its intentionally odd name: The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories, the last phrase being the critical one in hooking me. With a glance at the contents, I discovered that the titles of three key stories (a Nebula-award winner and two nominees) performed permutations on three words—island, doctor, and death: “The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories” not only hinted at a debt to H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau—another echo of which Brian W. Aldiss had just published as Moreau’s Other Island—but also set the stage for stories to follow: “The Doctor of Death Island” and “The Death of Dr. Island.”

In much the same way as Wolfe’s title did so long ago, the title of Barker and Pugmire’s latest collaboration intrigued me as it simultaneously identified genre (or sub-genre), inspiration, and important words. Or rather, types of words, since gulfs and dream prepare not only for the central novella, “In the Gulfs of Dream,” but also for such titles as “The Stairway in the Crypt”; “Among the Ghouls”; “The Temple of the Worm,” with its nod to Bram Stoker; “The Stone of Ubbo-Sathla”; “Within One Earthly Realm”; “A Dweller in Martian Darkness,” in which a one-word addition avoids a near-quotation from HPL; “Elder instincts”: “The One Dark Thought of Nib-Z’gat”; “Descent into Shadow and Light”; “The Horror in the Library”; and others.

My first reaction to the title and contents page echoed my reaction to The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories. On one hand, the overall title identified; on the other, it seemed slightly redundant—a collection featuring “In the Gulfs of Dream” and stories with such directly evocative titles could only be Lovecraftian.

My second reaction, however, was to brace for stories well beyond the lukewarm Lovecraft so frequently served up as new and ingenious. I have read and enjoyed other Barker-Pugmire efforts and thus anticipated more than simple imitation or clumsy pastiche. And the initial tale, “The Stairway in the Crypt” immediately fed that anticipation. The opening paragraphs paid homage not only to Lovecraft but also to Poe, through the introduction of a “beloved late wife” with the exotic name of Lunalae Kant née Morelle; an emotionally fraught internal monologue identified by copious use of italics; and a setting in a deserted New England cemetery. The tone, the atmosphere, the feeling was perfect Poe.

Until I hit the sentence, “I thought he was bullshitting me, but one look at his face told me otherwise,” followed by an slighting reference to “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.”

Bullshitting! Really? In Poe?

I was startled for a moment at the apparent break in decorum. As the story progressed, however, it became clear that there was more involved than a mere drop in diction level. “The Stairway in the Crypt” alludes to Poe and Lovecraft, yes, but it is also about two authors, one whose imagination is saturated in things-Poe and another who is just as strongly a Lovecraftian. While each does not hesitate to speak in the language of his respective hero and bandy around such pointing terms as sepulcher, Marceline, windswept graveyard, melodramatically, and the always obliging eldritch, both introduce moments of raw, modern, colloquial diction into their dialogues. In effect, they consciously draw attention to one great similarity between their idols: their use of distinct, clearly recognizable, easily parodied styles.

This is important to the collection because almost without exception, while the stories incorporate plots, characters, treatments, themes, and images that resonate with readers of Lovecraft, they most obviously (at least for me as retired professor of literature and creative writing) function as vehicles for demonstrating language as horror, for the incremental revelation of the unknowable and indescribable, for the final moment of gorgeousness and allusion and suggestion that incorporates the entire horror. In other words, for approaching horror in precisely the way Lovecraft did. And as such, these stories are worthy successors to the master himself.

Indeed, as with Lovecraft, a number of the stories seem essentially plotless soliloquys, several only few pages long, one complete in less than two sides. Plotless, however, is not meant to imply pointless or empty. In Barker’s “The Horror in the Library,” a man reads an old book. That is basically the story. And yet…and yet, through the magic of evocation, allusion—of the sheer force and majesty of language—it succeeds as a crystallization, a distillation, an encapsulation of terror, repulsion, and dread.

I have focused on only one of many excellences of In the Gulfs of Dream and Other Lovecraftian Tales. The authors’ command of characterization (in the Lovecraftian sense of an often unstable first-person narrator enduring the impossible…right now); landscape, even when their quest for dreams and horrors leads them to a darkly Bradburian Mars; and pacing and momentum, whether for a short-short or a novella—all lend strength and convict to their storytelling. Haunters after darkness and fear will find much to recommend the book.