Thorn Publishing, February 2014

Kindle, $.99

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

It’s something of a recent phenomenon in eBooks—packaging a number of highly rated novels as a ‘boxed set’ available on Kindle for less than a dollar. It results in a powerful publicity tool for the authors whose books are included and an equally powerful opportunity for a wide range of entertaining reading.

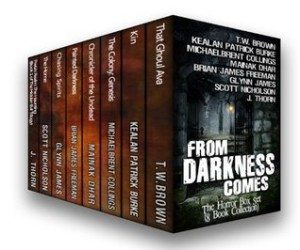

From Darkness Comes: The Horror Box Set contains eight complete novels: That Ghoul Ava, by TW Brown; Kin, by Kealan Patrick Burke; The Colony: Genesis, by Michaelbrent Collings; Chronicler of the Undead, by Mainak Dhar; Painted Darkness, by Brian James Freeman; Chasing Spirits, by Glynn James; The Home, by Scott Nicholson; and Preta’s Realm: The Haunting, by J. Thorn.

Since I’ve now read two of the selections, I suppose it is appropriate for me to put in my two-bits worth of reviewing.

I read Michaelbrent’s The Colony: Genesis when it first came out. It is the opening salvo in a multi-volume zombie-saga, the final installment of which is scheduled for later this year. Since I’ve already spoken to some degree about it (and the comments will be reprinted in my forthcoming Chain of Evil: The JournalStone Guide to Writing Darkness), I will say here only that each volume of the series confirms my faith in my son’s storytelling abilities.

The second book in the set—Scott Nicholson’s The Home—was new to me, even though it was first published 2005. I had tried to read another Nicholson novel several months ago but was unable to finish it, so I approached this one with some trepidation.

And at first, the trepidation seemed warranted.

In many ways, The Home seemed like an extended cliché. The setting is a 1930s monstrosity, a featureless grey building that had originally housed an insane asylum—with all of the accoutrements of horror that such places feature—and now is home to several dozen children. The children themselves initially come across as typical: social misfits that include the fifteen-year-old bully and his sycophantic, army-jacketed flunky; an anorexic/bulimic girl whose distorted body-image controls her thinking; a sensitive twelve-year-old who, abused mentally and physically by his psychiatrist father, had retreated into a mental world fashioned along the lines of his favorite tough-guy actors. The institution’s director is an alcoholic whose surface religiosity masks his own deep flaws, including his need to administer corporal punishment whether deserved or not. The head scientist is determined to make his name as a psychiatrist—mentioning the holy trinity of Freud, Skinner, and himself—regardless of the physical and emotional trauma to his victims/subjects. Social workers are reduced to their nickname, “shrinking” their charges’ self-esteem while bolstering their own.

Then something remarkable happens. Gradually, as the major characters assemble and begin the task of revealing themselves through their words, their actions, and, most critically, their thoughts, The Home moves from threatening to degenerate into a clichéd mess and instead strikes out in unusual and original directions.

Largely through layers of motivation, self-revelation, and deft narrative pacing, Nicholson transforms what could have been ordinary into a constantly evolving study of barriers—between sanity and insanity, science and religion, and, most importantly, life and death. With each page, the story develops greater and greater complexity and ambiguity, leading to a conclusion that is apocalyptic in the oldest sense of the word—an ‘uncovering,’ a ‘revealing’ of truths beyond anything the characters might have imagined.

As a story, The Home offers entertainment and intrigue while inviting readers to reconsider many of their assumptions about sanity, truth, life, even reality itself.