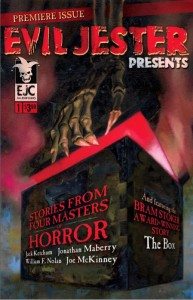

Jack Ketchum, Joe McKinney, William F. Nolan, Jonathan Maberry

Evil Jester Press (Grant/Day Media)

December 2013, $3.99

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

In my early teens, I—along with my brother and sisters—read. We read all the time. Our mother had to pour both the cereal and the milk for breakfast at the counter, then hand us our bowls, because if she set the cereal box or the milk carton on the table, we would fight…over who got to read them first. During summer vacations, when we weren’t playing school in the basement, once a week we were allowed to walk to the neighborhood branch of the library and check out as many books as we could carry. We would usually finish our own selections the first day or so, then pass the books around until the four of us had read all of them…and whine because we had to wait until the next week to get more. Our mother was probably the only mother on the block who had to set an alarm each day to make sure that her children went outside to play for at least an hour.

But we only read books.

I don’t remember a single comic book in our house; and if we had any, they would have been innocuous, G-rated offerings.

In fact, I didn’t discover weird comics, dark comic, horror comics—whatever you wish to call them—until one Christmas when we visited my father’s older brother and his family. While the parents chatted about people living and recently dead that we had never heard of, the four of us and our cousin settled in a corner. Tracy opened the bottom drawer of an old desk and revealed his treasure-trove: a stack of EC Comics.

We devoured them. There were enough of them to keep us occupied for the entire visit. To this day, I don’t think my parents had any idea what kind of comics we were reading.

But then, of course, we went home.

And back to books. Glorious, thick, text-studded books.

Oh, we re-read Tracy’s comics once a year or so when we went back to visit, but somehow, comics and I never quite clicked.

I was a bit taken aback, then, when Taylor Grant of Evil Jester Press emailed a few days ago to offer me a .pdf of Evil Jester Presents #1. I took it as a compliment, of course, but wasn’t quite sure what to expect. After all, a comic book?

Okay, call me a snob. But at least (I think) I am an open-minded snob, because I not only read the four graphic tales in the issue but I enjoyed them tremendously, both for the inherent storytelling and for the intriguing combinations of word and image that, taken together, turned straightforward words into something far more entertaining.

The four stories are linked by a single, obvious theme: horror. Each presents a something that, while appearing normal on the surface, is threatening, dangerous, destructive.

Jack Ketchum’s “The Box” (adapted by Taylor Grant, with art and colors by Beni Lobel) begins innocently enough. A boy on a train asks the man next to him “What’s in the box?” The man shows him…and nothing is the same after that, for the boy or for his family: father, mother, and two sisters. We never find out what is in the box; nor does the grief-stricken father who, at the end haunts train cars, desperate to find the man and the box, to see for himself what it was that so utterly and so inevitably destroyed his family.

The artwork parallels the story perfectly. Subtle changes in details, in the way the boy in particular is depicted, tell the tale almost as powerfully as the words. Colors shift from the bright red of the box in the first frame to darker, more threatening, almost monochromatic grays in the final frames…focusing finally on the striking blue eyes of a man gone mad.

Joe McKinney’s “Swallowed” (adapted by Aric Sundquist, with art by Steve Polls and Esther Sanz), begins almost as a riff on the last page of Ketchum’s story. Again there is a sense of oppressive darkness, setting the scene with a snake, her clutch of eggs, and a bayou-style house in the distance. From that point, we follow the snake’s point-of-view as she returns to the house where she was once kept as a child’s pet and, entering his room…eats him. But, as one expects with McKinney, there is a sudden, inexorable, and (for the snake) fatal twist that abruptly links the story to his novels, and does so with a strong sense of inherent symbolism and parallels the Ketchum’s conclusion: “I’m hungry.”

William F. Nolan’s “Small World” (adapted by Taylor Grant, with art by Salva Navarro) thrusts us immediately into horror. A lone character, running down a darkened street, chased by…shadows. Desperate, he manages to reach his refuge, a make-shift home in the storm drains. After reminiscing about how and why humanity has declined to—possibly—a single man, himself, he decides to return to his old home and retrieve what has become his private symbol of hope—a set of medical books given to him by his wife. While there…well, if I went any further, spoilers. Of the four, this story seems the least fulfilling. The central panels are vivid and precise in recalling the calamity he has survived, but in doing so, they are forced to directly reveal what, in a longer format, might have been opportunities for suspense and narrative revelation. As a result, the final panels seem rather blunt, declarative. Still, it does work, given the limitations of space.

Jonathan Maberry’s “Like Part of the Family” (adapted by Aric Sundquist and Taylor Grant, art by Nacho Arranz and Esther Sanz) begins in darkness, with the city black with the passage of a great storm and a nicely noir-like plot. A gorgeous woman seeks out a private detective to protect her from her ex-husband, owner of a nightclub called Crypt. The detective enters the club alone and forces his way into the owner’s office. Tensions escalate until the owner calls in four thugs to convince the detective to back off. Unfortunately for him, they are vampires; unfortunately for them, that makes absolutely no difference.

Readers familiar with Maberry’s “Strip Search” (Limbus, 2013) may recognize the detective from his last name, “Hunter,” as well as the tone and milieu; suspecting how the story will end does not, however, diminish interest in the tale nor in the way it is told. As it approaches its conclusion, the story quickens: frames shift from large to small, establishing a kind of internal rhythm paralleled by the almost stichomythic quality of the dialogue. Everything speeds up until the climactic frame and—Wham!—all is revealed.

Taken as a whole Evil Jester Presents#1 promises much and delivers on the promises. Strong stories, appropriate and inviting artwork, masterful presentation—all work. The tales might not have been as spine-tingling to a jaded sixty-six-year-old as those ECComics were to a fascinated thirteen-year-old, but reading EJP rescued them from the depths of memory…much to my joy. Grant/Day has done a fine job in their first effort; and more is promised in the final words of Maberry’s tale, “The End…?”