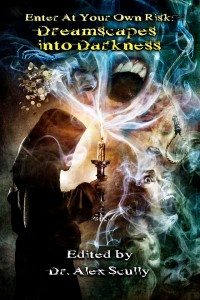

Edited by Dr. Alex Scully

Firbolg Publishing

April 24, 2015

Reviewed by Sydney Leigh

Once again, Firbolg Publishing knocks their yearly anthology out of the park. The theme of Dreamscapes into Darkness is desire, and what might happen when all you wish for isn’t quite what it seems. Dr. Alex Scully is profoundly well-versed in the history of Gothic fiction, and culls stories from modern writers which perfectly complement classics from Gothic masters like Shelley, Lovecraft, Le Fanu and Lawrence—tales which Daniel Knauf so elegantly states in his Introduction “have long languished out of print, buried alive in the curled, yellowing pages of defunct pulp magazines and newspapers. Waiting, yes, for you.”

But while the inclusion of these classics is a signature of Firbolg’s yearly series, and, by all means, a literature lover and book collector’s dream, it’s their modern counterparts that truly stand out in this anthology.

The poem that leads off the anthology, Tanya Jarvis’ “Incubus,” lends a dark, sophisticated flair to the collection with its terrifying visage: “This bed of nails in her stilted house / seems, if anything, to encourage him…” Fuseli’s The Nightmare is immediately called to mind, but the poet does more justice with her words than the artist does with his brush:

she couldn’t tell him from the dark,

the cold prick of her own loneliness

sitting on her skin, a shirt of nettles,

the metallic bite of a bitter river

whose current drags her down to sleep.

Jarvis’ piece is polished, pointed, and just about as gothic as poetry gets; a complex portrait of desire and disgust. “Thus pinned, heart’s rod and piston / laboring under unforgiving weight…And she’s breathing fire, now, speaking / infernal tongues, all of them licking at once…”

In “Bad Things Happen” by Nathaniel Lee, the narrator runs a small blog site and lands an interview with the Vandal King, one of the many “metaphysicals” who scourge the earth in roughly human form. Lee’s idea here is gloriously macabre, his language and turns of phrase almost hypnotic. Anthology lovers will undoubtedly appreciate why Scully chose Lee’s as the kickoff tale.

“Why do you do this?” the narrator asks the Vandal King. “‘Why?’ he asked, idly uprooting flowers as we walked. He met my gaze, eyes glittering like a slick of oil over a bottomless ocean. ‘Because I can. Because it’s there. Because it’s beautiful.’ I glanced back the way we had come. Disarray and chaos, with a soundtrack of broken sobs. ‘Where is the beauty in wrecking things? I don’t see it.’ ‘I do.’ He smiled at me. His teeth were crooked and dirty. I suppose I’d expected fangs.”

Their interview leads them away from the heart of the city and into the outskirts, where the Vandal King destroys things along the way with a mere caress—“It was the first miracle I had ever witnessed.”—and elaborates on his rationale with the telling of a fable which unravels into a disquieting discovery for our narrator, and yet a divinely dreadful ending for us. “Oh…there are the fangs.”

“First Horse” by Rob Smales contrasts slightly from the rest of the pieces with its tribal legends and Native American setting, but the dreamlike sequence that tells the story of a young boy needing desperately to be seen perfectly captures the essence of this anthology’s theme—be careful what you wish for—and in a befitting dreamscape directly into darkness.

JG Faherty’s “End of the Road” is a strong piece in the collection. Though not quite as representative of the theme as the others, there’s no question why Knauf named him one of the “contemporary masters” in the Introduction. Faherty’s writing sets the ideal tone and feel for this tense, dramatic ghost tale: “The rough, pitted blacktop road meandered through the landscape like a blacksnake, with scattered stars and thin sliver of moon providing just enough light to see by…” In the end, we question where the true darkness really exists, and which ghosts we should fear most.

Jonathan Maberry’s “Property Condemned: A Story of Pine Deep” is, quite simply, a lesson in storytelling. Maberry takes the idea of a haunted house and turns it inside out, upside down, and backwards. It’s an emotional, evocative, and extremely effective tale with more “wow” moments than most novels.

Nancy Hayden adds another rich layer to the anthology with “No Man’s Land, which we’re told in the Author Biographies was “inspired by a trip to the 100-year old Western Front battle fields and trenches in France and the unseen things that linger there.” Her visit to the grounds certainly influenced her story, and the setting is both authentic and disquieting with its grisly history. For such a short story, Hayden succeeds in taking us on a tense journey with some creative plot devices—and her last image is impeccably dark, horrific, and unforgettable.

Holly Newstein’s “The Bondage of Self” is a sad and disturbing tale…a raw glimpse inside a bitter, loveless marriage and a clever, twisted tale of revenge gone wrong.

“The Other Place” by Patrick Lacey touches upon themes of bullying, told flawlessly from the perspective of a young narrator plagued by otherworldly visions which prove more appealing than his lonely, tragic life. Lacey ends this one on a memorable note, to say the least.

Gregory L. Norris’ “One More” is superb; his gorgeous prose floats gracefully, rich with imagery and deftly lonely in tone. Against his better judgment, a nameless character is lured into a house where Norris pulls out all the stops and shows us what true horror really is…and his final twist is simply masterful.

“The Morgue” by Aaron Gudmunson is by far my favorite piece of his—I’m a devout Gudmunson fan, but this is one of the best and most memorable shorts I’ve read in a while. His first person narrative renders this tale all the more unnerving, his dialogue between two friends growing—or being pulled?—apart flawlessly executed. The gothic atmosphere and imagery in this story is a fine example of what Firbolg’s editors seek to elicit from today’s writers.

Bo Balder’s “Shelley Unbound” is exquisite—modern gothic literature at its finest—an accomplished modern companion piece to Shelley’s “The Mortal Immortal.” Balder’s language shows mastery, a feudal-tongue licking the pages: “Her thoughts shoot over her irises likes shoals of silvery fish. I cannot read them fast enough. Yet something tells me she will not welcome my suit. I shall not give up so easily. I untie her, extend my hand, which she accepts, and pull her forth into the new world. I will show her automobiles, flying coaches and moving pictures. She will be entranced.”

After listening to B.E. Scully read in person, it’s difficult not to hear this story in her voice, which makes “The Son who Shattered his Father’s Dream” an even more effective piece. Aside from her trademark cultured, literary writing style and a finely told story, really, this line is what it all boils down to: “‘No, dad. Maybe you just dreamed the wrong dream,’ was all that his son could reply.” Scully is extremely skilled in the art of constructing a tale for a theme such as the one Firbolg has designed for this anthology, and that one line demonstrates it brilliantly.

Roxanne Dent’s “Heart of Stone” is a tale of seduction and obsession, set in the romantic, fog-draped French countryside and revolving around a crouching statue with horns, wings, and a strange power over our narrator. Dent creates some nice imagery and employs the theme of the anthology with an innovative and memorable ending.

In Joe Sherry’s “Yellow Bullet,” we spend the entire duration of the story on a bus…but more importantly, inside the mind of its driver. And Tom Walsch had it all worked out—knew exactly what he wanted to do—but once again, the lessons these tales have taught us are that we must be careful what we wish for. Sherry’s deft use of anaphora with a single line is what makes this story’s tragic ending all the more compelling.

The clever, brilliant, and witty Kurt Fawver is a superb addition to this line-up of contributors, and closes out the anthology with a decadent interview satirizing the nature of a submissions call…and the lengths to which both publishers and writers will go to meet it.

The rest of the stories are all worthy of mentioning: Lawrence Buentello’s tale of a lonely man who gets more than he bargains for when moving next door to a “Graveyard”; the unusual place a white water rafting trip takes K. Trap Jones’ brave narrator in “The Weathermaker”; an ironic twist of fate to which writers can relate all too well in Frank R. Stockton’s “His Wife’s Deceased Sister”; and Joe Powers’ “Lead Us Not Into Temptation,” a thoroughly unsettling story of a child molester on the loose—one that both beautifully embodies the theme and proves Firbolg is a press that does not look away from difficult subject matter:

“He’d heard it said that a predator—and that was what he unquestionably was—was never cured, his urges always bubbling just beneath the surface, threatening to boil over at any time. A leopard never changes its spots, they said. A monster is a monster. All it would take was the right trigger and they would fall right back into their old ways. Through those doors of the big box store he spotted the very catalyst in question, in the form of a five-year-old girl.”

Firbolg Publishing prides itself on the horror it brings readers involving something beyond mere violence and gore—the unknown, the “shadowy world of terror out there”—they also showcase writers of the highest caliber, both new and established. In Dreamscapes into Darkness, they claim “Passions become obsessions. Obsessions become manias. And sometimes, manias turn into nightmares.”

They’re right. So, enter at your own risk—it’s worth the wager. This one comes highly recommended.

Great review. All the stories in this collection have something unique to offer and Jess Landry hits on them all. Landry’s review is well written, thoughtful and a winner. One of the best reviews I’ve read.