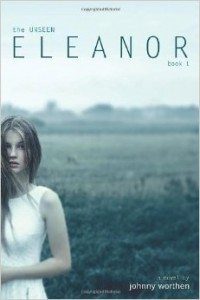

Johnny Worthen

Jolly Fish Press, July 2014

Trade paperback, eBook

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Over the past few months, I have had the enviable opportunity of reading several books that I consider extraordinary…not a term that I use lightly in writing reviews but that in this context is apt and fully justified. The handful of books are connected by a number of threads.

First, they were all published under the label of horror, and in its own way, each developed to the fullest potentials stories about the interaction of monsters with humans, even when the monsters were human.

Second, even though technically horror or horror-related, none of them emphasized blood-letting for the sake of blood-letting or gruesome and grotesque for the sake of gruesome and grotesque. While none of the authors shied from violence or disturbing images, such things appeared when the story required them, not when the writers apparently tired of characters and simply decided to be done with them or intuited a lull in the pacing and remedied the lack by a flurry of gore and mayhem.

Third, all of the stories were character-driven, interesting me sufficiently in the unfolding lives of complete strangers that I was caught up on their conflicts, inner and outer, and in the directions their lives would take, whether for good or for evil.

Fourth—and most significant—I was able to enjoy the books as a reader rather than being pulled away from the text to function, officially or unofficially, as an editor, consciously noting sentences or structures or scenes that I would have changed if I had been in charge of the manuscript or wished that that author had changed before publishing the book (and that included one novel that I was in fact at the time editing for JournalStone). Yes, I might have noticed an infelicitous phrase here and there, but never anything that forced me to stop and change hats, to mentally re-work passages to make them more efficient. Instead, I was able to enter the world of the story, live there for a comfortable span of hours, and finally emerge more aware, more deeply contemplative, altered, even to some degree shaken by revelations about what it is to be human…and what it is to be a monster. For me, that sense of seamless narrative (even when interrupted for such non-essentials as eating and sleeping) meant that the storytelling had succeeded at the highest level.

The most recent of these books was Johnny Worthen’s YA paranormal/horror novel, Eleanor.

In a number of ways that curt description fails to do justice to what Worthen attempted and what he achieved in Eleanor. On the surface, it falls under the rubric of “young adult”: its principles are high-school sophomores in a small K-12 school in rural Wyoming. Many of its actions center on coming-of-age discoveries about self, identity, and—especially—sexuality, treated at a controlled level and with a limited explicitness appropriate to the intended audience. It covers roughly one year in Eleanor’s life, although flashbacks fill in necessary blanks for her and other characters interacting with her. It treats the conventional angst of adolescent with particular skill, becoming neither maudlin about nor dissociated with that difficult stage of life.

At the same time, however, it is not young-adult fiction…at least, not exclusively. Its adult characters—especially mothers—are crisp and believable, mature, counterfoils to the excessive emotions the younger generation feels and, especially in Eleanor’s case, a powerful model of humanity at its finest, helping the sometimes-cynical Eleanor seek and occasionally find the best in those around her. More importantly, however, the novel speaks to both YA and adult audiences in its modulation between generations. There is more to Eleanor than is immediately apparent, and the slow, gradual discovery of her nature and her abilities makes her far more than simply a pubescent cliché.

Similarly, to refer to the novel as “paranormal” or “horror” is ultimately misleading. True, there are mysteries to be unraveled, not a few of which connect to folk culture and beliefs, to incursions into the reality of experiences that cannot be verified by scientific observation. And true, the novel makes inventive use of several traditional monsters, mentioning werewolves, doppelgängers, shapeshifters, and skinwalkers…all permutations on venerable staples of horror that have captured imaginations for generations. But—as with some of the finest horror tales—these images are not given center stage. That is reserved for a human, a fifteen-year-old female who faces serious challenges and choices, whose actions lead to inevitable consequences, and who is required to assume responsibility for her choices and live with the consequences. She is not acted upon, not even by the pressure of genre-expectations. With each change in her situation, with each new disclosure of who and what she is (meticulously paced and controlled by seemingly innocuous words and phrases throughout), she must think beyond the monster and into the depths of humanity.

What results is a binocular view of a teen-age girl. She is the invisible student in any high-school class, the one no one notices and who takes great pains to keep it that way. She is bright but satisfied with a “B” rather than an “A.” She is athletic but chooses not to draw attention to herself by standing out in any sport, even when it means playing well under her abilities. She is plain, in her own estimation as well as in the eyes of most who know her; only special people who develop special connections with her comprehend her beauty. She is not one of the popular clique but neither is she the constant target of bullies. She is simple assumed…her presence roughly as important as that of a wall or a door. The story as such begins when her invisibility is challenged at the most fundamental level—by a boy.

At the same time, she is a monster (not a spoiler as such, since evidences abound from the opening pages). She must not—she cannot—be recognized for what she is; that has happened in the past and those she loved suffered for it. She cannot allow herself to be seduced by the appearances of a normal life, even one complicated by the fact that her mother is dying of cancer, throwing typically adult responsibilities onto Eleanor. She discovers many of her abilities at the same rate as readers discover them, surprising herself with actions and reactions, then struggling to fit them into her view of monster-outside-the-purview of humanity. She wants desperately to trust, to love and to be loved, yet she cannot allow either, knowing the hurt that will inevitably fall upon those nearest to her.

As the subtitle indicates, Eleanor does not tell the full tale, yet it comes to a satisfying conclusion. Eleanor arrives at a respite but not a resolution. She is still what she was, a being caught between two worlds, between past and present with no permanent prospects for a future. But at least a few of her problems have been solved and she—and readers—can begin to hope for possibilities. It is, in a word, extraordinary.