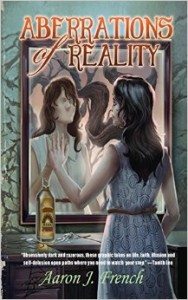

Aaron J. French

Crowded Quarantine Publications (UK), 2014

Trade paperback, 383 pp., $12.99

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

The back cover of Aaron J. French’s collection, Aberrations of Reality, promises “tales exploring occultism, religiosity, spirituality, metaphysics, and the supernatural”—and the book more than fulfills that promise. From the first entry, “Here & There”—which begins “The moment they nailed you to the cross you forgot almost everything you knew”—to the final words of the final story, “The Year of Our Lord”—“From space, the earth appeared as a giant white dot, ever swirling, ever churning, devoid of landmasses or bodies of water. But beyond that, things of this nature are quite impossible to explain”—the twenty-two stories examine individual’s struggles explain, to break through, to contact, to understand, to embrace the other…other realities at first only intuited but that gradually become ideals, objectives, goals, and death-ridden obsessions. Some struggles end in transcendence; others in death; and still others, in layers of complexity and ambiguity that in themselves help define human existence.

Many of the entries, as exemplified by their titles, are linked—however ephemerally—to the Christian tradition: “Doubting Thomas,” “Paladin,” “The Christ,” “Tree of Life,” and “The Year of Our Lord,” for example. It takes only a few moments of reading, however, to discover that none of them follow traditional expectations, that each wrenches familiar terms and concepts into new modes of thinking about spirit and life. Certainly none of them are programmatically connected to Biblical models. Even that most evocative and perhaps least understood of Christian symbolic writings, the Revelation of St. John, undergoes completely unanticipated permutations in the aptly—and perplexingly—titled “{[California Sea + Cosmic Man] – Humankind} + Anadyr, Russia = Apocalypse.”

Interspersed with these are other titles, equally suggestive of entirely different modes of storytelling. “Dwellers in the Cracks” is heavily influenced by Lovecraft, a weirdly distorted version of Lovecraft’s imagination that transmutes inexorably into a distant descendant of Poe’s “The Black Cat,” yet that ultimately declares its independence from either as both dwellers and cracks assume new references. That story provides one of the keys to reading all that follow—French’s adroit juxtaposition of belief and hesitance, his willingness to merge contemporary religious and spiritual questions with images that move beyond the dream-visions of Poe and Lovecraft into something relevant and accessible.

What separates French’s stories from so many others is that they often bring characters to the brink of enlightenment—where most tales fade into a panoramic view of clouds and sky—and then cross that boundary with them, to experience…well, peace, or indifference, or freedom, or some other state distant from the euphoric exultation of Biblical redemption. Indeed, it is the sense of vast understatement that makes French’s exercises so powerful, as in “Golden Doors to a Golden Age,” in which imagery and plot development suggest one possible ending, when in fact (mild spoiler ahead), at the climax the character “just simply felt okay.” And in the context of this story—and others—okay is well enough.

Questions of the nature of reality recur throughout the collection, perhaps most explicitly in “What Lay East, Lay West,” a strangely functional tale of a single character moving through an indefinite desert that evokes the Old West, always moving East seeking something, always chasing answers to the inevitable question, “What is real.” Appropriately enough, there is no precise resolution to his question…only the inexorable approach of death. Others find momentary respite in dreams, then grapple with the same question couched in different terms: what is the connection between dreams and life, and what happens when one spills into the other. And perhaps more crucially, what results when the character can no longer differentiate between the two.

French’s stories are always edgy, in content and in execution, pushing boundaries and redefining conventions. The nearly two dozen contained in Aberrations of Reality are no exception. Some will speak immediately to readers; some may fail to resonate on first reading, gaining power through the context of other stories—but all will lead readers into new territory, suggest new answers to age-old, imponderable questions.