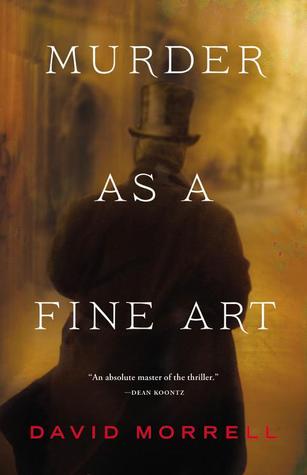

David Morrell

Mulholland Books, May 2013

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Remarkable.

Compelling.

Intriguing.

These and other words appear (perhaps too frequently) in review after review. I try to avoid them as much as possible since they suggest an unusually high level of achievement and should be reserved for such.

But in the case of David Morrell’s Victorian masterwork, Murder as a Fine Art, they are entirely appropriate, even in sequence: Remarkable, compelling, and intriguing.

The novel is a foray into history-as-fiction, with a foundation in carefully researched, highly informative (and relevant) historical data and a superstructure of meticulously crafted fiction. It brings together two sets of individualized characters that would, in the year 1854, normally have had little to do with each other.

The first is an official duo: a detective in the London Metropolitan Police, trained in the latest techniques of observation and focus; and a constable assigned to him, whose heartfelt wish is to prove himself worthy of eventually becoming a detective himself. The two of them undertake an investigation of a particularly grisly, brutal series of murders that—point by point, almost beyond the limits of belief—mimic one of the first mass murders in modern England, the Ratcliffe Highway murders of 1811. Forty-three years later, it seems, the killer has returned to add to his list of victim.

Detective Ryan and Constable Becker arrive at the scene where a crowd—soon to be a mob—has already gathered in the full heat of panic. Step by step the two officers work their way through the crime scene—itself something of a new concept at the time—simultaneously revealing crucial elements relating to the murder and illuminating Victorian sensibilities toward crime, criminals, the police, and life in general. The scene ends, almost comically, with Constable Becker manfully struggling to maintain the integrity of several footprints that nearly certainly belong to the killer. Unfortunately, two pigs, one on each side, take it into their minds to attack him. What follows is, again, almost comic: almost, because the slime containing the footprints is polluted with human waste—common at the time—and should Becker be injured, he would run the serious risk of infection at the least, cholera at the worst. In Victorian England, nothing is as simple as it seems.

Eventually, Ryan and Becker realize that the murders follow precisely not only the 1811 tragedy but also the explication of it in a recent essay, “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts,” by the notorious writer and opium-addict, Thomas de Quincey. While still trying to find out how to bring de Quincy to London from Scotland, Ryan discovers that the writer and his daughter, Emily, are already in London—and thus the second set of characters. Ryan initially decides that de Quincey must have more to do with the crimes than merely writing about them and is in fact deputed by the Home Secretary to place de Quincey under arrest.

Instead, Ryan, Becker, de Quincey, and the indefatigably independent and open-minded Emily join forces to uncover the identity of the killer, to determine why the recent spate of deaths so closely follows that of 1811, why the killer has secretly decoyed the de Quinceys to London, and why he persists in mercilessly and bloodily baiting both the police and the de Quinceys with their inability to capture him.

By concentrating on these four characters, Morrell deftly juxtaposes two modes of thinking and understanding. The detective and the constable see themselves as objective; they base their actions on perceived evidence and reason. They think things through according to their understanding of the world in which they live, the society that surrounds, and the backgrounds they bring to the task. De Quincey, on the other hand, is uniquely—and, for those around him—disquietingly subjective. Part of the time, when he is under the influence of his ‘medicine,’ copious doses of the opium-based laudanum, de Quincey functions in something like a fugue state, acting on visions and conclusions that seem not to have any basis in ‘reality.’

The disjuncture between the two modes of knowing forms one of the continuing themes of Murder as a Fine Art. Stolid Victorians to the core, the police officers rely on what they consciously know. Visionary and philosophical, de Quincey often acts on “thoughts and emotions we don’t know we have,” on a dissociation of the mind into two parts that prefigures Freudian concepts by over seventy years; in a word, on the subconscious.

The conflicts between conscious and unconscious, between social mores and expectations and human impulses and urges, between drug-induced possibilities and accepted actualities provide much of the impetus for the novel. The crimes are simultaneously conscious acts and unconscious acting-out. The characters—both heroes and villains—persistenly confront the disparity between Victorian ideals of action and expression and the realities of 1854 London.

And over-riding all is the presence of the ultimate villain (no spoiler here): Opium itself. The drug that makes life bearable for some, agonizing for others. The source of the wealth that supports the London upper-class, with all of its predilections and assumptions; the source of the poverty that drives the lower classes to crime and death.

Let I begin to sound as if Murder as a Fine Art is some kind of historical tract, let me be clear. Morrell incorporates vast quantities of history into his story, but it nonetheless remains a story. As such, I found it immensely readable and simultaneously enlightening.

And, to be slightly repetitive, remarkable, compelling, and intriguing.

Highly recommended