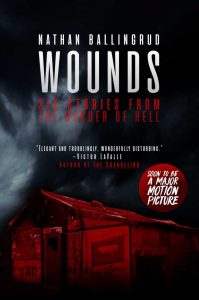

Wounds: Six Stories from the Border of Hell

Nathan Ballingrud

2019

Saga Press

Reviewed by Gordon B. White

Nathan Ballingrud’s new collection Wounds: Six Stories from the Border of Hell is a monstrous, monumental collection. It’s an obsidian obelisk on a shore of charcoal-colored sand that will not just draw the reader’s eye to strange sights on the shore, but entice them into the unexplored depths. These stories are seeds, but in that way they are wonderfully self-contained, yet possessed of the potential for strange, expansive life. If you know Nathan Ballingrud as an examiner of the horrors lurking beneath the veneer of the everyday, prepare to meet him as a captain of a terrible vessel that plunges headlong into Dark Water. The subtitle “Six Stories from the Border of Hell” isn’t a mere teaser—it’s a warning and key.

Wounds consists of six stories, beginning with five that have been previously published and culminating with the original novella “The Butcher’s Table.” Unlike some collections, where the story order is an aesthetic suggestion, readers here are advised to take the stories as they come. The horror-noir “An Atlas of Hell” starts the collection, and the pirates-meet-Satanists adventure beyond the veil “The Butcher’s Table” ends it, but there are enough shared narrative elements and thematic ties emerging out of each story from start to finish that Wounds is a feast best enjoyed in the order presented. The unfolding revelations, the way that moments that came before click and fall into place with the moments after is engrossing and shows a careful hand. More than mere cerebral satisfaction, too, readers will feel the swell as it becomes evident Ballingrud is not merely weaving narrative webs, but stitching together emotional ones from sinew, bone, and pumping hearts.

Elsewhere, Ballingrud has referred to Wounds as a “seedbed,” and what a garden this is. The table of contents doesn’t give too much of a hint, but as the reader makes their way through the stories, little connections begin to emerge from the twists and turns. The town of Hob’s Landing, for instance, was once home to both the eponymous character of “The Diabolist” as well as Jeremiah Wormcake, the ghoul host of the macabre “Skullpocket” fair. Dark figures appear in the periphery of one story, only to come close enough to touch in another. There’s a wonderful way in which certain threads tie themselves together that I won’t mention here, but by the end readers will have been given our own Atlas of Hell, and we see how the different continents of each story connect.

Despite their unifying elements, the six stories in Wounds run the gamut of settings and characters. “The Atlas of Hell” introduces Jack Oleander, a hard-boiled occult book collector recruited by the mob to find said map. Of course, his mission is complicated when the prize corrupts the reality around it, blurring the borders of here and Hell. “The Diabolist” then jumps full in, introducing an imp from the Love Mills of Hell (and if you’re wondering how that could be a hellish creation, you’ll find out) mistakenly plucked from the pit by a lovelorn diabolist. When the diabolist’s daughter tries to take up her father’s work, however, things take a turn for the (even) worse. “Skullpocket” then fully introduces the town of Hob’s Landing in the most charming but still chilling story in Wounds, a consideration of love and the passage of time which balances a casual, even delightful, grotesquerie of ghouls and severed heads with the truly traumatizing experiences of coming of age and the end of life.

After that palate cleanser, however, “The Maw” drops readers into a literal Hell on earth, where portions of the now so-named Hollow City have been ceded to demonic presence. Of course, abandoning hope is difficult for humans, even in the mouth of Hell, and so lonely survivor Carlos recruits the tough young Mix to guide him into the occupied city in search of his runaway dog. Then, after the mounting fantastical horrors of the previous four stories, “The Visible Filth” (which is now a major motion picture also titled Wounds) returns readers to something closer to the real world. In this novella, New Orleans bartender Will finds a cellphone with a series of disturbing pictures that begins to open up wounds both physical and emotional in those around him … wounds that may serve as doors for something terrible, or wonderful, or both.

The crown jewel and capstone here, however, is the previously unpublished novella “The Butcher’s Table.” Both a culmination of Ballingrud’s ability to shade the unreal with human depth and an exciting foray into new territory, this historical horror story follows a group of pirates hired to transport Satanic cultists and cannibal priests to the very shore of Hell. The Butcher’s Table of the title refers to the name of the ship as well as the setting for the feast along Hell’s shore, but it signifies more than that, too. The butcher’s table is the wide sea, as well, and the open land of Hell itself—it’s any expanse or flat plane where the greatest threats aren’t demons and devils, but the hidden passions and secret plans of other people.

While the stories’ ties to a literal Hell is the most obvious shared element, what really unifies these stories, as strange as it may seem, is their preoccupation with the forms of love. There is love that fuels destructive impulses; love that spurs one to make mistakes; unrequited love; squandered love; and perhaps even pure love, too, which has the power to redeem, but only for a time and only within limits. Here is love that drives diabolists and priests and ghouls and pirates and men and women onwards into that undiscovered country of Hell. Here is also love, however, which might bring them back. Hell is other people, but in Ballingrud’s worlds, love is Hell, and so love is other people, too, for all the hellish complexity that entails. This is the circular nature of Wounds—each horror is an opening, a revelation, but one that loops back until it is simultaneously interior and exterior, like a Möbius strip.

As far as the writing itself, there isn’t a wasted word. Ballingrud writes about horrible things with such directness that the prose becomes almost invisible while rendering the nightmarish images crystal clear. This is essential, because the strange realms and unlikely monstrosities that Ballingrud has conjured require a balance between horror and beauty, phantasmagoric nightmares rendered with textbook accuracy. More than just the mutilations and monstrosities, however, Ballingrud autopsies his character’s psyches with similar precision—the co-protagonists of “The Maw” are immediately recognizable in their stubborn hurt, while the festering relationships in “The Visible Filth” are as anxiety-inducing as the literal open wounds. Without slipping into indulgence, each observation of inner turmoil and its external embodiments is doled out with sublime control.

Nathan Ballingrud’s Wounds: Six Stories from the Border of Hell is without a doubt one of the best, most accomplished horror collections in recent memory. It’s a grisly joy to see Ballingrud’s creativity given the space to unfold and flourish before doubling back on itself, free to chart its own atlas and water its own seeds until it forms a dark garden of tongues and fingers that grapple with the weight of being and wrestle down the dual existence of Hell and love. By excavating the raw human elements and allowing himself the freedom to stitch them together in nightmare patterns, Ballingrud crafts stories that do what only the best can: they horrify, they humanize, and they return from Hell with a map of the new, fearsome places inside.