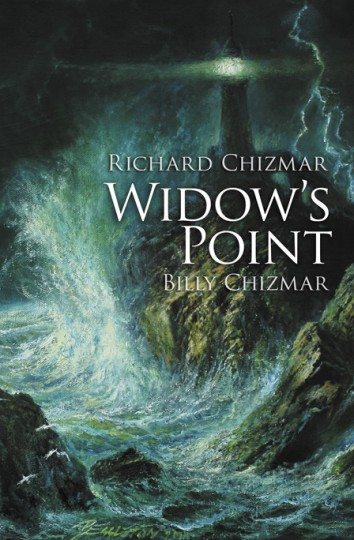

Widow’s Point

Richard and Billy Chizmar

Cemetery Dance

2018

ARC

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

At just after 6:00 pm on Friday, July 11, 2017, well-known writer on the supernatural Thomas Livingston enters the Widow’s Point Lighthouse in the far northern reaches of Nova Scotia. The moment he enters, two things happen. The lighthouse’s eccentric owner locks and chains the door—the only exit—behind him. And the video camera he is using to document his experiences suddenly goes blank.

He is to remain in the lighthouse, alone, until 8:00 Monday morning, when the owner will unchain the door and release him.

At least, that is the plan.

But the Widow’s Point Lighthouse has other designs for Livingston. Built in 1838, its reputation as one of the most haunted structures on the Atlantic coast is well-earned. Over the decades, it has been the scene of sudden deaths, suicides, gruesome murders, and inexplicable disappearances. And, as Livingston is soon to discover, it has lost none of its potency over the years.

The Chizmars, father and son, have selected a perfect location for their chilling tale of hauntings, betrayals, and death. Isolation is essential for effective horror, and what is more isolated than a lighthouse constructed on a deadly promontory that has itself been the scene of shipwreck and death? The structure is inherently eerie and frightening (as the stark black-and-white illustrations by Glenn Chadbourne aptly capture), with its winding staircase, its two hundred and sixty-eight steps to the top, and its wrought-iron catwalk.

It is the ideal location for a story that teeters magnificently on the precipice between the uncanny and the marvelous, in the precarious realm of the true fantastic. Several decades ago, Tzvetan Todorov posited a definition of the fantastic that used as its primary exempla ghost stories and other tales of the arcane (for an explication of his ideas, please see http://michaelrcollings.blogspot.com/2014/01/the-fantastic-uncanny-and-marvelous-in.html). Widow’s Point provides a particularly appropriate test-case for Todorov’s theory. Like the lighthouse itself, the story stands between the fact-based world of Harper’s Cover and the supernatural world of shadows and specters.

Much of the resulting ambivalence is due to the Chizmars’ brilliant choice of narrative approach. Widow’s Point is told in present tense, a point of view that I normally dislike. But in this case, it works flawlessly, since each scene, each episode is recounted, not by an innately imperfect narrator (at one point, Livingston admits to lying about what he claims to have seen), but by means of strictly objective video/audio footage or audio recordings. The result is the verbal equivalent of such found-footage films as Blair Witch Project and Cloverdale, shot in jitter-cam, in which the narrator/main characters are not allowed to comment on events but merely react to them, their reactions caught on camera or tape. When the video goes blank on Livingston’s recorder, as it does inside the lighthouse, we are left with a rigidly unbiased account of words and sounds.

And given the meticulous pacing and careful transition from the anticipated to the frightening—things moving on their own accord, food mysteriously rotting after only a few hours, an equally mysterious diary that thrusts Livingston into past horrors—one point seems unassailably true: Widow’s Point Lighthouse is haunted.

Or is it?

Because the tale also includes an official police report detailing events after 8:00 on Monday morning and a psychological evaluation shortly thereafter by a psychiatrist assigned to study the audio and video footage that suggest another, uncanny but ultimately explicable interpretation of events: Livingston was an undiagnosed schizophrenic who buckled under the pressure of isolation and stress. And the Widow’s Point Lighthouse is not haunted.

Then in a masterstroke, the Chizmars conclude the report with a single, chilling sentence: “The case is, and shall remain, ambiguous.”

Ambiguity. Is the lighthouse truly haunted or not? Is Livingston recording his own mental breakdown, or has he in fact tapped into the supernatural? Can the audio and video evidence be trusted, or must it be discounted as the result of a fractured personality?

All that remains to cap a near-perfect story is the revelation that another intrepid ghost-hunter is negotiating to spend a night alone in the Widow’s Point Lighthouse. When asked why, he answers rather arrogantly: “Because it’s what I do. I’m an explorer, seeker. Great discoveries are rarely achieved without great risk.” The mystery of the Widow’s Point Lighthouse continues.

Highly recommended.