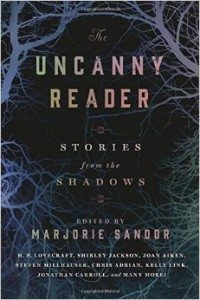

Edited by Marjorie Sandor

St. Martin’s Griffin

February 2015

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Over the past several years, I have enjoyed the opportunity of reviewing a number of anthologies relating to dark fantasy, to speculative fiction, to horror. Many of them have been outstanding, collecting stories that stand as high points in their specific sub-genres, moments of high artistry by their authors.

Of these many, however, two stand out as particular milestones.

The first is Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural (1944), edited by Herbert A. Wise and Phyllis Fraser. This book is important to me for two reasons. First, it was my initial introduction to the breadth and depth of dark fiction, stimulating my imagination in ways that would have been inconceivable had I not read it. I can still remember individual moments when certain stories “came together”—when language, images, and ideas fused so perfectly that I experienced the physiological frisson that is the hallmark of the finest horror. And, as noted in the review, I still have my copy of that book on my shelf where I can easily find it. The second reason is that it is, quite simply, one of the finest compilations of historical horror available; in 1944, to be sure, it was considered cutting-edge but by 1967, when I purchased my copy, it was already the sine qua non for neophyte readers. Anyone interested in tracing how horror came to where it is today would do well to begin with Great Tales.

The second remarkable anthology is A Darke Phantastique: Encounters with the Uncanny and Other Magical Things (2014), edited by Jason V. Brock. In key ways, it seems the Great Tales of the twenty-first century, collecting contemporary stories that mark definitive shifts in society; in ethics and morality; in language and expression; in attitudes among individuals, tribes, and peoples—all clothed in the cloak of indeterminacy and exploration. It seems in its own way as much on the track toward classic-status as the Wise and Fraser collection.

And now, there is a third, one that encompasses the dimensions of both, displaying not only more fine fictions but a clear sense of how they came about, their ancestry, and their world-wide interest.

The Uncanny Reader: Stories from the Shadows, edited by Marjorie Sandor, collects thirty-one tales from nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century writers, beginning with E.T.A. Hoffman’s “The Sand-man” (1817) and concluding with Karen Russell’s “Haunting Olivia” (2006). Along the way, it pays due homage to the greats: Poe, Bierce, Chekhov, Kafka, Lovecraft, Jackson, Oates—names without which the collection could not pretend to completeness. At the same time, however, it introduces readers to less-familiar stories by men and women; stories originating in English and stories translated from a number of other languages; stories from the US and the UK and more traditional European nations and stories from Egypt, Germany, Russia, Sweden, Uruguay, and Zambia. At over 550 pages, the collection represents the finest of nearly two centuries of investigating “Shadows.”

For such a massive book, the cover price seems more than fair; even more so since Sandor’s “Unraveling: An Introduction” is well worth the cover price alone for its exquisite care in defining—delimiting and mapping—the extent of the “uncanny.” Quite properly, she begins by examining her term: Uncanny, ‘seemingly supernatural’ or ‘mysterious.’ Immediately she pauses on one word…seemingly, identifying it as the key to the entire collection.

Seemingly. Inherent uncertainty of outcome. Stories that, set in realistic landscapes with realistic characters, nonetheless end in hesitation, ambiguity, indecision. And in spite of that—or better, perhaps—because of that, they satisfy more completely than self-contained, self-explanatory stories might not. If on the one hand, a clear resolution would indicate the supernatural, and on the other the natural or realistic, in between lies the possibility of both…or neither.

These are, in effect, Schrödinger’s Box stories…only no one actually lifts the lid at the end to discover either the corpse or the living cat.

These are, as Sandor tells us, stories about potentialities:

When something that should have remained hidden has come out into the open

When we feel as if something primitive has occurred in a modern and secular context

When we feel uncertainty as to whether we have encountered a human or an automaton

When the inanimate appears animate. Or when something animate appears inanimate

When something familiar happens in an unfamiliar context

Conversely, when something strange happens in a familiar context….

And on…and on.

Although tempted to talk about favorites (and there are many), I decided not to in this case. Merely presenting the skeleton of a story is often enough to diffuse the eeriness within, and at other times would require my bringing my version of resolution to a story that intentionally does not have one. Suffice it to say, each story is one-of-a-kind tale-telling that may seem to lead in a specific direction but that might…just might…carry the reader into uncomfortable, disquieting, occasionally frightening, always intriguing directions.

Open the book and give it a try.