The

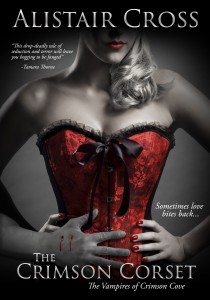

Alistair Cross

August 1st, 2015

Reviewed by Michael Aronovitz

Let’s get this part out of the way quickly. The Crimson Corset is a good story. It is also a vampire story, meaning it is a good vampire story, but before we set off to Google the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning, we need to first establish that the initial part of the equation here is more important: Alistair Cross wrote a good story. As for the vampire theme, we could split hairs and investigate the history of Gothic fiction to see how much faithful testimonial Cross chose to layer onto the archetype versus how distinctly his thumbprint stands out, but that too quickly turns into a philosophical argument between those who feel the need to maintain “standards” and others who might just want background music for a new canvas. Both sides are interesting and there are aspects of either that could apply to The Crimson Corset depending on your bias, but again, that is not the focus of this review, nor the novel, I would quite humbly argue.

Still, I suppose we must initially discuss the vampire issues for “vampires sake,” simply to get the question of base-credibility settled for the traditionalist die-hards. Taking on a vampire story is similar to a musical group that wants to call itself a “rock band.” Just having instruments and a hit record doesn’t cut it. There are certain things you absolutely must have to fly that particular flag, and instead of going through the specifics of the more insignificant side of this analogous parallel, it is with thrift and brevity I would claim that certain artists are not in rock bands, mostly because they favor things other than the guitar/blues/garage focus at the root of their creative philosophy, preferring to highlight issues like whether they make music you can dance to or not. And to set things straight right here, I am not claiming that EDM, Hip-Hop, The Black Eyed Peas, Hannah Montana, or thousands of other musical styles and personalities are “bad.” They just ain’t rock.

The Crimson Corset on the other hand, is a valid vampire story, that which does justice to many of the conventions that have been passed down from generation to generation, all with an original flair and a modern relevance. Plainly, the “Crimson Corset” is both a place (a club next to a bar and grill called “The Black Garter”) and a piece of clothing our villainess Gretchen VanTreese wears, made of pieces of her dead mother utilizing the bones as ribbing and the teeth for buttons. The set-up is that in the town of Crimson Cove there are good, peaceful vampires who have learned to resist killing humans and bad vampires who want to feed freely and exercise their dominance over our kind. Both sects exist within the confines of an uneasy treaty about to be broken: Gretchen VanTreese at her club with the tunnels and torture chambers beneath and Michael Ward living at his tranquil lodge across town called “Eudemonia,” laden with a health spa, cabins, thick woods, healthy dining, and glorious office space.

The above-mentioned adversaries have colorful vampires working under them, Michael’s in a more conventional hierarchy of bodyguards and advisors, including Winter – with his white blonde crew cut; Nicholai – the Russian Immigrant and former watchmaker; Collette – the sexpot with porcelain skin and crystal blue eyes; Arnie- the simpleton; Oz – a new member; Lucian – the magician; Emmeline – a feminist; Cedric – a proper aristocrat straight from the British landed gentry and Chynna – the lion tamer (my favorite). Gretchen’s gang is more difficult to pigeon-hole, since many of them are victims she drugs with “venom” for the pure purpose of feeding, making them work in different capacities as bartenders, body guards, and sexual toys. She has two Irish twins named Aiden and Ambrose, who she acquired in 1849 when they abandoned the tedious life of mining and fled to the hills to prospect for gold. She keeps them at the foot of her chair like dogs. There is Annette and there is Rose – addicts working as waitresses in the club; Violet and Scarlet – former hookers who act like sexual mermaids in a huge tank in front of the bar; Scythe – a hulking bodyguard who has a penis so big it is nicknamed ‘Vlad the Impaler;’ Sebastian – with his irresistible thin Italian face and ponytail and Jazminka – a six foot mercenary with a Slavic accent, flat top haircut, and thigh high black leather stilettos, looking awfully close to the Mother Russia character in the 2010 film Kick Ass, but if the boot fits…

As for the “nuts and bolts” of vampire lore, Cross alludes to or engages many of the myths through intensive action or clever exposition: silver, stake through the heart, holy water, garlic (as an absolute non-factor here), crosses, sunlight, and the rest of the grab-bag, all addressed with tact and brought to us in context like old friends. In terms of moving this genre cornerstone into his own arena, die-hard vampire fans might find it interesting that the mainstay of Cross’s answer to tradition lies in the idea of the “Sire,” a human that can actually reproduce with a vampire, creating a being that has both the powers of the night and the day. While there might be other vampire stories that have entertained this discussion in one form or another, the most familiar storylines stop at the idea of “breeding” by biting, rather than procreating for hybrids.

The concept of the “Sire” and the idea that a vampire can infect a victim with venom that causes automatic allegiance to the violator (and drug-like dependence) both remain intriguing links to the established folklore, if only that they play off the standard like a nod to posterity. Still, there are other things at play outside of vampire tradition in The Crimson Corset that successfully draw the reader into this world, some technical, some thematic, and others stylistic in the form of superior scene mechanics.

First in terms of structure, Cross establishes an omniscient voice that floats from protagonist to antagonist in the same given scene units. Usually, I am the first to advise writers not to do this. Stick to first person and third person limited. Keep things clear. In this case however, Cross seems to exercise a certain mastery of this complicated voice technique with effortless transparency. I could go line for line to prove that it works in specific chapter segments, but for our purposes here I hope you trust that we would share similar semantic sentiments. More globally (and retrospectively), the omniscient voice doesn’t work in most cases, first because a character will often fade and wither if the reader is yanked out of his or her point of view. The greater offense however is the inevitable residue of author’s ego that usually accompanies “playing God” with everyone’s thoughts all at once. Here, Cross seems to have the uncanny ability to root and re-root us comfortably within characters in action, on the fly, as if it was handed to us on a silver platter, and as for the latter, there is simply no ego involved, not here. In fact, it seems Cross merges in and out of the role of narrator so “silently” (for the lack of a better adjective) that the “narrator” as entity is ghosted, almost haunting the book with occasional support beams and brushstrokes. Not only is that masterful. It is a new sort of literary device, presented in a manner that merges structural technicalities with theme. That is the true hybrid.

In reference to emblematic platforms, there is a layering technique Cross orchestrates within the aforementioned structural phenomenon, as illustrated first through the stark difference between the Crimson Corset Club and Michael Ward’s Eudemonia retreat. To be blunt, the Corset has a huge decorated windmill apparatus in front of it, a club inside that is no more than a front, and a set of dark pathways beneath leading to chambers of torture. The original, base-board attraction of “the vampire” is the pristine passion of darkness, the seductive idea that one gives him or self over to another utterly and erotically. The Corset is a parody, its entrance looking like hole seventeen on a boardwalk miniature golf course, its bar a dark, unsatisfying cave only made half-interesting to its patrons and addicts by “magical mermaids,” and its secrets buried at the ends of dirty channels like corroded arteries in a hideous being that doesn’t quite realize it’s dead. Eudemonia on the other hand has expansive woods, lovely log cabins, lush gardens, and soft peach walls in the style of a Spanish Hacienda. Still, the dichotomy is not so simple. This is not good versus evil. It is the real versus replica, and out here in the real world, where many prefer conversing on Facebook as opposed to live and in person, it seems Cross’s thematic settings are not so simplistic or antiquated.

If we are going to enter a lair, like it seems Cross has so politely invited us to, we should consider what is at the center of his intricate (and external) weaving of structure and theme. Good scene mechanics often rely on the things that are cleverly foreshadowed, and if you are looking for set-up and pay-off, this novel will not disappoint. There are so many great moments in the piece that it would be difficult to encapsulate them here, and I also want to avoid too many specifics because killing surprises makes for bad commentary (as does too much summary). I will point out two things to look out for however, two scenes that are particularly disturbing and frightening, so much so that the spoilers won’t ruin the journey, I promise.

First, Gretchen VanTreese is simply one of the most intriguing antagonists I have recently had the pleasure of despising. Hot? Of course, but any romance writer with half a brain can turn a guy on with tits, ass, and cheekbones. Gretchen is…well…sort of different. She is short, maybe four foot eleven. She has “flawless alabaster skin, almond shaped emerald eyes, and satiny white-blonde hair.” Okay. Good. But she also has blood red lips, an expressive mouth, and big teeth that shine. In terms of what might be considered “common playbook material” versus credible triggers, she becomes kind of “real” with the teeth and the pixie height, but add in the hourglass waist made inhumanly thin with the help of “that corset,” the spectacular legs, and…oh…not to mention her pet spider Lilith that she lets dance on her pussy, and friends and neighbors, we have a character we can’t look away from (even if we are stupid enough to want to).

Moreover, there are scenes in here that are simply terrifying, the kind that when reading you don’t just sit back, rub your goatee, and say, “Hmm, that works.” Again, without giving too much away, I would venture to say that the torture of Sebastian in the basement has the scariest build-up I can remember since the boyfriend went downstairs for a beer in Halloween. Picture a tall vampire tied at all four limbs and stretched like an “X” with his bones twisted and broken so he cannot so easily rejuvenate. His head is limp and laying on one shoulder. Cade edges down the dark, gritty stairs and the form before him moves slightly, the eyes coming open showing their whites, a smile forming…

The Crimson Corset is a good read. There is a colorful cast of characters, a clever plot, and an intricate structure. Cross takes the vampire as a story-type and uses it as a launching point for good fiction. There are surprises and jumps and starts, sex and death, beauty and gore, something for everyone. I am not making the argument that Cross tries to alter convention, for he makes tribute to tradition with the best of them. My claim is that he came at this with a good story in mind, and then was bold enough to actually execute it.

As a last point that connects back to theme, more specifically parody versus the new, I would pose that central characters Cade Colter and his brother Brooks, along with the town sheriff Ethan Hunter are drawn by Cross in an effort to break or at least widen the male prototype. Cadence and Brooks are arguably feminine names. Brooks eats health food and looks at himself in the mirror more than a high school girl going on her first date. Cade talks to a fern and adopts a stray cat. He reads romance novels in secret as does Ethan Hunter. The three are constantly asking about one another’s feelings and or comfort level, and often notice what another male is wearing or something as trivial as what he smells like…not an overpowering cologne mind you, but just normal grooming, sitting next to him in the car. There is an abundance of the fake-gay jokes in the dialogue, typical of guys horsing around, like Brooks coming through the door and saying to his brother, “Honey, I’m home!” or the same character patting his stomach and saying “I have to watch my figure” or the same character saying “What, no hug?” and Cade returning the banter with, “I’m afraid you’ll crush me with your great big muscles.”

Some might think Cross did this unconsciously, but there is a scene through which it is decided that for protection Cade should stay at Ethan’s place, and not only do they call it a “sleepover,” but Cross named the following chapter “Sleepover.” Then later in chapter 54 the town sheriff sleeps over Cade’s house. This was intentional, perhaps a bit overdone, but an absolute must if we are going to destroy parodies, finally crushing that fucking windmill and filling in those foul dirty tunnels. On the other side of this, I will tell you that Cade performs incredible heroics in this piece, his brother exhibits unthinkable bravery, and Ethan dates the hottest female non-vampire in town, mortician Sheila Leventis. These guys do manly things and think manly thoughts, they just don’t burp, fart, and sit on bar stools complaining about how bad their local professional sports teams suck ass. Of course there is a possibility that Cross had an agenda to paint male characters (and refer to them even in general narration) as females might prefer men to think and talk, because female readers buy books, but I don’t believe this is so, at least not entirely. Cross made a statement here about the real and the replica, and he was brave enough to put any and everything in the superstructure straight into the crosshairs as part of the experiment. That was the cerebral endeavor.

And it was a hell of a fun read on top of all that.