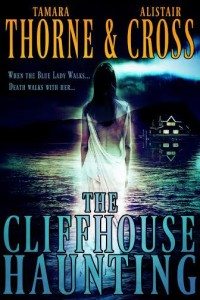

Tamara Thorne and Alistair Cross

Glass Apple Press

March, 2015

Reviewed by Michael Aronovitz

To best enjoy The Cliffhouse Haunting, it might be necessary to revisit the origin (or at least the semi-recent history) of the carnival, and note the way that Thorne and Cross superimpose elements of the bright chaotic festival upon the more traditional horror backdrop of “the haunted hotel” with all the jumps, starts, and frights that frequent this particular lexicon. Before we unpack all these components however, it should be stated up front that this novel is fun to read. The pacing is lightening, the characters are humorous, the setting is gorgeous, and the monsters are vicious. The plotting is as intricate as one of those labyrinths Dickens symbolized in pieces like Bleak House, and the gargantuan cast of characters reminds us of epic blockbuster films of the 1950s. Still, this piece is not antiquated. Quite cleverly, Thorne and Cross cherry-pick history when it suits their modern vision of horror and comedy to create a fresh vision of what I might call “delicious reversal.” At times during this piece, it seems by design that the reader cringes at the behavior of the lead characters and marvels at the poetic beauty of the savage. We are part of this exotic parade, and Cliffhouse is more about mirrors and masks than killers and ghosts.

Of course, many allusions are not entirely parallel, and Cliffhouse as “carnival” is not perfect in its symmetry. Easter and traditional carnival rituals bookend Lent, and this novel is certainly not about Jesus. It also takes place around Labor Day and the more fitting setting may very well have been the French Quarter during Mardi Gras as opposed to the San Bernardino mountains of Southern California. Still, this piece is all about masks, personas, and alter-egos, as well as the idea that Cliffhouse brings the “ID” to the forefront instead of hiding him behind the tired façade of our social norms. A story about regular people acting regularly in a big old regular hotel wouldn’t be too intriguing, yet Cliffhouse is one big public street party, chock full of fireworks, Civil War reenactments, and various drunken themed festivities. In what plays as familiar carnivalesque ritual, there is feasting (an Oktoberfest celebration where a serial killer wins ribbons for sausages containing horrific ingredients) role reversals (the police chief Jackson Ballou constantly being shown up both intellectually and physically by his girlfriend Polly), temporary social equality of the dissimilar (Sara Baxter Bellamy, heir to a lucrative hotel falling in love with a talentless assistant who stays in his abusive business relationship with “authoress” Constance Welling for a nauseatingly long time simply because he is so unprepared for the world he cannot find another job until it is handed to him) and permitted rule breaking (as caretaker Walter Gardner risks incredible liability through astounding poor judgment, in telling nine year old Carrie and her seven year old brother Tommy ghost stories involving native girls in slave labor, a woman drowning her children by weighting their bodies down with stones in a sacrifice to the naiad, and a dead women on a swing with her intestines torn out).

But before judging Thorne and Cross for what might seem literary miscues, we have to broaden our focus not only in reference to the concept of “carnival,” but the purposeful dichotomy of monster versus citizen that these authors so boldly propose as an overall paradigm. Clearly, one of the messages here is that the Cliffhouse setting brings out the carnival as a farce, exposing its paraders to irreverence, parody, and degradation. The “innocent” characters have their insides showing, both mentally and physically in this psychotic circus of a world that actually removes the mask of social propriety. Why else would Dr. Roger Siechert (behind the guise of drinking the evil, infected water) wonder aloud in transparent and purposeful author’s exposition why he is saying such rude things to his patients? Why else would the religious Pat Matthews become the night time graffiti vandal and paint bright red penis’s across the front doors of local businesses while his well-to-do wife sits at home making extra money giving phone sex? A mortician’s wife (named Beverly Hill no less) is pelted with tomatoes in a grocery store, and during a girl fight one of the participants rips out the other’s clit jewelry. These people are possessed. By themselves. By their inner demons, and in true carnival fashion, we laugh and cringe in the same way we do when Jonathan Swift modestly proposes we eat our children in order to better preserve national capital.

The fascinating part of the binary here is the monster, especially since it is placed in such opposition to the reanimated “citizen.” Plainly, Thorne and Cross have invented horrific figures of incredible beauty even in their bloodiest, grisliest moments. In terms of the latter, Thorne and Cross play the “inside-out” theme physically at the hands of their murderers in direct counter-point to the metaphorical exposure endured by the hotel guests. As mentioned before, a dead girl is left on a swing with her entrails wrapped around the chains, in effect, holding her in place. A nurse is ripped open with a blender motor by a lover who has a fixation with anal cleansing. While these two examples are brutal in their literal connotation, the symbolic tie to the exposure of the hidden (or the “inner” or the “ID”) is difficult to miss.

There is also a play on masking in reference to the “evil-doers” that makes us all too aware that the dark world might contain more aesthetic congruity than the one playing out under the bright lights of the Cliffhouse lobby. The killers here form a triad, a religious symbol in itself suggesting some sort of spiritual credibility, but more, the masking element between the three players in their “cooperation” with each other demonstrates a universal (and frightening) human truth. The Blue Lady of the Lake uses Hammerhead and the maniac doctor to carry out her heinous work for her in a clear illustration of dissociation. Not that these killers have any sense of conscience, but is it not the “team” that relieves the individual of literal blame? During the holocaust, the superior officers were miles away from the actual atrocities they drew up on paper, and the ones pulling the switches that let out the gas were simply following orders. In this manner, Thorne and Cross invent the most complete characters in the story, not because they need to be relieved of guilt, but rather that most bad guys (if we are to believe in them) think they are good guys. The Blue lady, Hammerhead, and Dr. Roger Siechert are scary because they believe in themselves tremendously and concede to the idea that they experience human need and dissociation in order to exist.

The monsters in The Cliffhouse Haunting possess complex and credible motivations, but their appeal is not limited to the cerebral. They are physically interesting and provide the visual poetry that counteracts the chaos going on in the hotel, the marketplace, and the front lawn in front of the band shell. The Blue Lady fills her victims with lake water and leaves wet footprints on the floor when she leaves. Creepy. Hammerhead captures souls, he believes, and traps them in mirror compacts that he keeps in a special hall. Mysterious. He also uses the claw part of a hammer to kill with a blow to the head, and if the victim is light enough he can hold the body up for a moment with one hand while making her look into the mirror he holds with the other. (Brilliantly written resourcefulness). And finally, for all of Dr. Siechert’s seeming incongruity in reference to the physical “beauty” of his compatriots and their given devices, he does, after all, kill “authoress” Constance Welling, and we can at least give him runner’s up status for that.

Tied in with the relative beauty of our antagonists, is the more intricate concept of mirroring, that which they do in a far more effective manner than the hotel owners and all of their guests. In terms of the latter, the mirrors are caricatures, poor replicas, parodies. Purposefully I think, Thorne and Cross never fully develop Adam and Teddy, Sara’s two fathers, who come and go more as a mechanism that proves the hotel has owners who walk the grounds and count the chairs once in a while. The Taffilynn’s are perverted anti-images of each other, and Jackson, like a ditzy cliché “blonde” goes out with Polly, the most masculine character in town, and tries to convince himself again and again that he really, really, really isn’t a total idiot for not bringing in the county boys or the feds as the body count rises. Even the lead characters who would demand the locus of our attention are inverted somehow, refracted mirror images that make us look through the wrong end of the telescope. For our hero, Sara Baxter-Bellamy has barely a quarter of the stage time possessed by Constance Welling, possibly the most dislikable character ever invented besides hack-psychiatrist Carl Leland in Tamara Thorne’s Eternity.

Plainly, the truest reflective architecture in this novel is erected by the bad guys at its periphery. In a literal sense, the blue lady fogs all the mirrors of the mortals and lives in a lake which provides a natural (though darkened) reflective surface. Hammerhead captures souls inside his compacts, and Dr. Siechert is so vain it is almost as if he parades in front of perpetual imaginary glass, showing off all the ribbons he wins at Oktoberfest. In terms of emblematic positioning, The Blue Lady, Hammerhead, and Dr. Siechert are preceded by The Blue lady, The Bodice Ripper, and The Gaslight Killer in the prior century, proving that as opposed to the hotel guests and townspeople, the bad guys are the tradition and the inevitable lens through which we will view history.

Thorne and Cross are clever. The plot they create reads effortlessly, and they make us laugh and cringe and widen our eyes, looking away from the text at times to say, “Oh no you didn’t.” But they did. In The Cliffhouse Haunting nothing is sacred, because the carnival is on. We are meant to let our guard down and laugh at those wearing masks that ironically expose our own most hideous truths. And from the sides, the edges, and the margins our dark adversaries stare at us with unyielding eyes, waiting for us to put down the book, to speak out of turn, to drink too much wine, or to slip on the watery footprints they’ve openly left in our paths. According to Thorne and Cross, the proverbial man in the mirror is no more than a loud, raucous joke. It’s what is reflected behind him, in the lake, in the well, and in the bottom of the dumpster that owns all posterity.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks