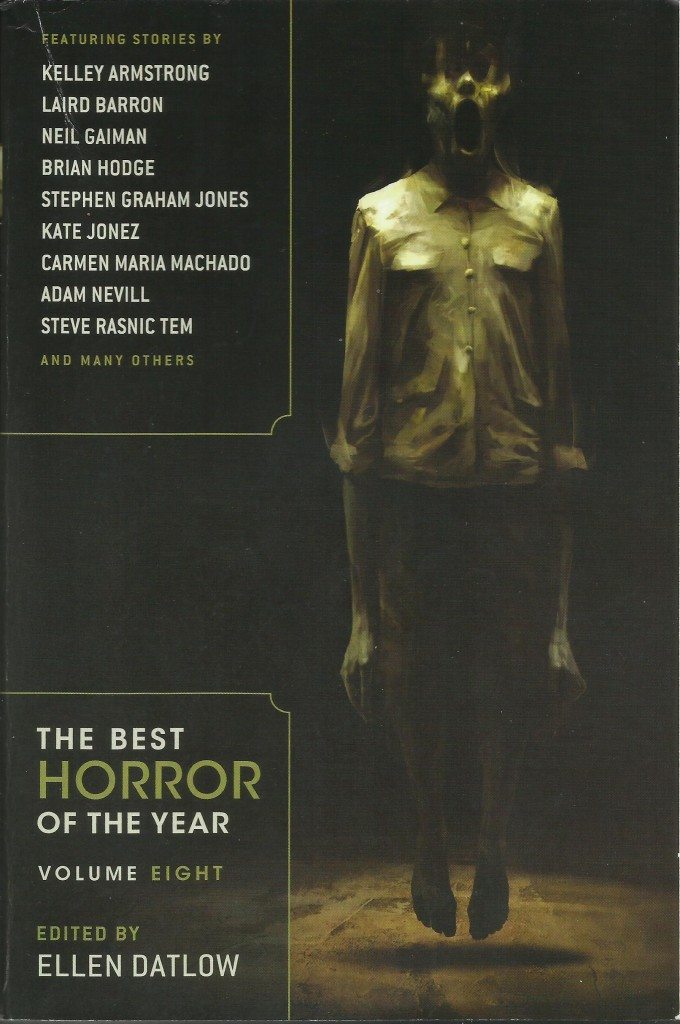

Edited by Ellen Datlow

Night Shade Books

June 7, 2016

Reviewed by William Grabowski

Ellen Datlow is one of the hardest-working, iconic figures in Horror, Dark Fantasy, and elsewhere. When she speaks well of a certain author, I—by default—make a point to seek out writing by that person. Datlow won, on August 20, a Hugo Award for Best Editor, Short-Form.

Hence number eight in Night Shade Book’s annual compilation, and 20 tales curated from print, online and, perhaps, cobwebbed nowheres isolated in extragalactic gloom. Opening with “Summation 2015,” the editor replays that year’s incredible fertility. These summations are pure gifts highlighting output both well-known and obscure—notepad opportunities aplenty.

What distinguishes Datlow-edited anthologies from most (not all) others is the mix of newer and not-so-new names tilting toward those less known. Among these are standouts like Gary McMahon, whose “My Boy Builds Coffins” begins as a claustrophobic set-piece and a boy with a fresh hobby as distressing as it is incomprehensible. Dread rises cold behind Mother’s and Father’s facile dismissals. I was glad having my smug “I know where this is going” certainty obliterated by McMahon’s sure handling of what feels like inverted folklore howling with phobic panic and loss. A nice setup for Tamsyn Muir’s epistolary, “The Woman in the Hill,” whose brave and empathetic women search for the missing after crossing an ominous threshold in a Waikopua hillside. Their horrifying encounters evoke awe, an indelible terror and mystery invading emotional control. The darkly mythic gravity reflects that of all ancient, or infrequently explored, landscapes onto which we project fantasies, fears, and despair—or is it the other way around?

“Wilderness remained a place of evil and spiritual catharsis,” warns Letitia Trent’s “Wilderness.” “Any place in which a person feels stripped, lost, or perplexed, might be called a wilderness”—which defines the events centering on a lone young woman waiting in a small community airport. In a very few pages, Trent manages a chilly unease as recently jobless Krista surveys the others—family types scarfing pizza, absorbed by cell phones, some casting suspicious glances and—following a break outdoors after the expected flight is announced as late-coming—questions at the single woman’s apparent menace. When police wearing gasmasks show up, and assure everything’s okay, the collective fear increases. Returning from the bathroom, Krista finds herself victimized by hysteria born of 9/11 and our sense of ever-intrusive surveillance. If you’re looking for an example of literary horror as mirror of psychosocial trauma, here it is. A masterful, unsettling work.

Speaking of unsettling, Laird Barron’s “In a Cavern, In a Canyon,” for me pulled off the exceedingly unlikely “trick” of evoking revulsion simultaneous with existential nausea. Akin to the tales from McMahon, Muir, and Neil Gaiman’s novelette “Black Dog,” Barron’s morphs the potently folkloric into contemporary horror whose elements of deadpan absurdity tear apart our casual assumptions of the universe as a mostly rational “place.” We very much like his smart, rough-edged protagonist still struggling in middle-age to unpuzzle her father’s strange disappearance, and life itself. She makes a tough decision, and choked my jaded heart. Barron’s ability to create a visceral sense of mystery—unfathomable, even anguished—is startling.

Other standouts in a volume of same: Reggie Oliver’s “The Rooms Are High,” Priya Sharma’s “Fabulous Beasts,” Stephen Bacon’s “Lord of the Sand,” Brian Hodge’s “This Stagnant Breath of Change,” and Carmen Maria Machado’s “Descent.”

The maturity, craft, and frightening imaginative power so evident in these writers gives me hope for the future of short fiction.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks