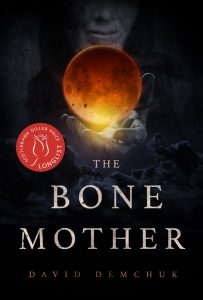

HN: Congratulations on your first novel! Let’s start at the beginning: For readers who haven’t yet read the book, The Bone Mother is probably best described as a mosaic novel – it is made up of dozens of vignettes from different characters’ points of view, each of them either what we might call a “monster” or someone who has encountered those monsters. Each vignette is titled for its narrator and most are illustrated with pictures from the Costică Acsinte Archive (also on Flickr here), which is a collection of photos by a Romanian photographer taken during the first half of the twentieth century. Can you begin by telling us about how these photos helped inspire the novel? In general, do you find external prompts to be helpful in your creative process?

DD: While I have been inspired by found objects and documents in the past, this was the first time that I have ever used photographs as prompts in a project. When I first conceived of The Bone Mother, I thought it would be a theatre piece (which it eventually was, in one form) or possibly a film, and so I felt I needed a strong visual element to work from. I had a general sense of what I was looking for, so went looking online for Creative Commons-licensed images that I could use. That’s when I found the Acsinte Archive which is composed of hundreds of public-domain photographs of Romanian villagers taken before and during WWII. I chose about two dozen photos of people whose whose voices I could potentially write in, and spent some time contemplating each of the images, getting a sense of that person’s story before I began. I wasn’t sure how well this would work when I started the process, but in the end I found it to be very helpful.

HN: The Bone Mother draws (or at least seems to draw) heavily from Slavic mythology and history – particularly Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Romania. While the characters’ stories each feel grounded in very specific folklore traditions, there are also intrusions from the outside world in the form of war (or, perhaps, different wars). What was it about this particular area, its mythologies, and the time frames that attracted you? Were these areas that you were already familiar with, or did you have to do research?

DD: My father was born in Ukraine and came to Canada with my grandparents in 1929, and when he was older he fought with the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada in the Second World War. So I heard quite a few stories as a child both about the war and about the legends and fairytales that he knew as a child. When I started the project, I knew that I wanted to return to these stories—and find ways to combine and contrast them. I used those stories as the starting point for some additional research on the region’s history, geography and folklore, and events in the area leading up to and during the war, and continued to research and make discoveries throughout the writing process.

HN: While most of the vignettes take place in the past, there are a handful of present day accounts told by the children or grandchildren of the monsters who – despite having lost contact with their roots during the post-war diaspora – are still dealing with their family’s past and historical legacy. These sections also tend to be longer and to contain the most directly visible narrative threads about the rivalry between our “monsters” and the Nichni Politsiyi (“Night Police”) who hunt them. I’m curious about the development of these sections – did the desire to create a temporally longer narrative lead you to seek out the right vignettes to tell them? Or, perhaps, was it that in the process of addressing certain themes, the narrative thread had to stretch out to tie them in? Was it something else?

DD: I started out with the intention of writing approximately 20 short pieces set in and around the war, with the hope that 13 of them would work together as a performance text. Those 20 pieces contained the beginnings of the overarching Nichni Politsiyi narrative, but I reduced their presence for the staged version (titled “The Thimble Factory”) to make for a shorter, more approachable evening. When I began to develop the 20 pieces into a novel, I decided the best way to expand on the material was to look at how some of the surviving creatures had escaped to the new land, and how they and their children grappled with their past and their legacy as they continued to try to evade the Night Police.

HN: Another notable aspect of The Bone Mother is that the vignettes are not merely stories about the characters, but they are stories told by the characters. Each section is a first-person narrative and self-report, which gives the reader not just an insight into the characters’ mindset, but serves to somewhat normalize the characters’ experiences (or at least their existence). How did you decide to use the first-person, rather than third-person? Do you think that your decades of experience writing for the theater and other work on dramatic scripts helped your ability to do this? How did you get into all the different mindsets?

DD: I have always been a strong monologue writer, and enjoy experimenting with a character’s voice and perspective. Years of practice from writing for theatre has definitely helped with this. First-person allows me to inhabit a character whose life and relationships are different from my own, and to explore the limits of their perception and understanding in a given moment—a key component to the kind of work I write. Sometimes I do a bit of preliminary character work or a very rough outline, but often I just dive in and see where the words take me. The photo prompts I used were very useful, giving me a tremendous starting point for each of the pieces.

HN: Normally I would ask you which vignettes you found easiest or most difficult to write, but you’ve already discussed that in a previous interview. So, instead, I’ll ask you which of the characters you felt the most connection to or sympathy for? Were there any characters that you struggled to empathize with or even found irredeemable? Were there any ideas – whether that be a folkloric entity, a social issue, or just a type of character – that you had wanted to include, but just couldn’t?

DD: I feel a connection with all my characters to some degree, even the most repellent ones. But (minor spoilers ahead) the ones I feel closest to are probably Nicholas the wolf-boy, Krisztina the rusalka, Sabina the ‘Green Girl’ and of course the title character. Andreas and Gregor are utterly repellent but fascinating nonetheless. And there is one whole strand of Eastern European folklore and fairytales that deals with talking animals—while I touched on this slightly in The Bone Mother, I wish I could have explored it more. Perhaps in a sequel?

HN: The Bone Mother has been well received by readers and critics alike. In addition to strong reader reviews, the novel received a starred review from Publishers Weekly and was not only on the long list for Canada’s most prestigious literary prize – the Scotiabank Giller Prize – but is actually the first horror novel to ever make that list. What do you think it is about The Bone Mother that connects with people? Beyond the evergreen appeal of fairytales and scary stories, do you think it has to do with the current importance of recontextualizing and telling stories from the point of view of the Other?

DD: I do think many people are fascinated by fairytales, and enjoy unusual or surprising takes on the stories from their childhood. Goldilocks would be a very different story if told by the three bears! I find the perspective of the ‘monster’ or the ‘other’ endlessly intriguing and have explored it throughout my career. I think quite a few readers find it frightening yet thrilling to allow themselves to see the world through a monster’s eyes and to confront the monstrosity inherent in humanity. In a world where it’s often difficult to tell good men and good deeds from bad, and where are values and virtues can be twisted and turned against us, we look to such stories to help us make sense of our lives and what’s happening around us.

HN: What’s next for you? Are you currently working on any further fiction, such as another novel? Do you have any plans to further explore the world that you’ve begun building in The Bone Mother?

DD: I have started a new book about a horror that has its roots in the oldest parts of Toronto’s and Canada’s (white settler) history. It has a difficult personal connection for me, so the challenge will be to find a way to tell it without overwhelming myself. And I do have some ideas in mind for a sequel to The Bone Mother, but that would be a little farther down the road. Stay tuned!

“A master of bowel-loosening terror” (The Globe & Mail), David Demchuk has been writing for stage, print and other media for more than thirty years. His theatrical works have been produced in Toronto, New York, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Vancouver, Chicago, San Francisco, at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and in London, England. The Bone Mother is his first novel, his first Giller nomination, and the first Giller nomination for a novel in the horror genre.

Website: daviddemchuk.com

Facebook: facebook.com/thebonemother/

Twitter: @david_demchuk