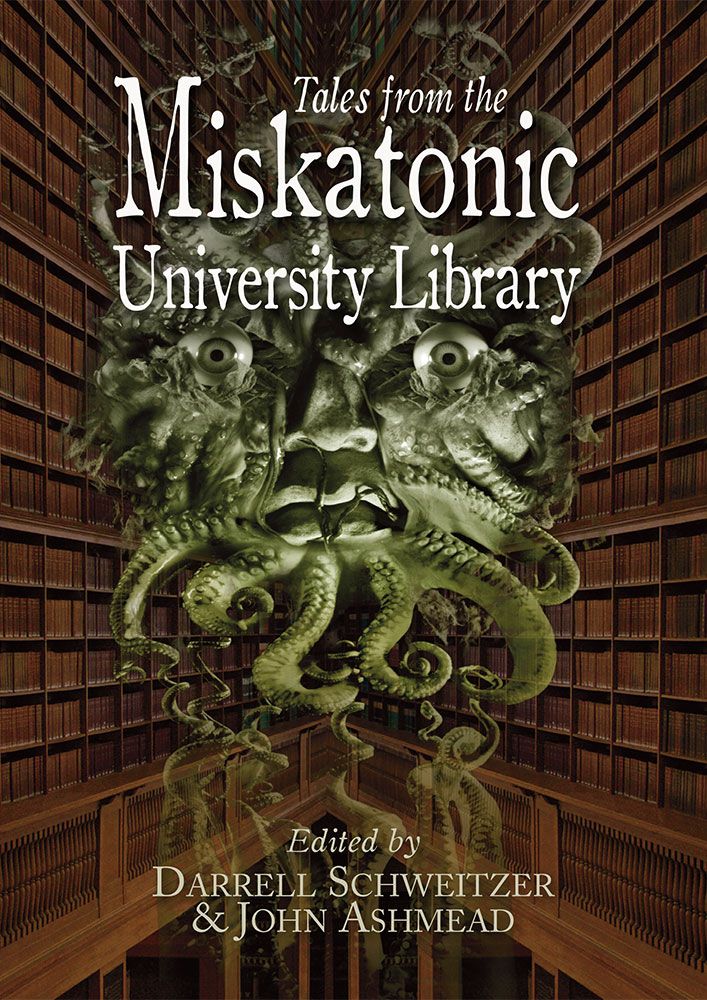

Tales from the Miskatonic University Library

Darrell Schweitzer and John Ashmead, Editors

PS Publishers

February 2017

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

Tales from the Miskatonic University Library is an anthology collecting two highly insightful introductions and thirteen stories (a lucky number, in this case) that touch in one way or another upon a rarely discussed topic in Lovecraftiana: Just how safe is the Special Collections section of that obscure university in the small town of Arkham, Massachusetts? After all, it contains some of the most dangerous volumes in the cosmos.

Working from this premise, the editors have assembled the most appropriately comedic perspectives on Lovecraft and his horrors that I have ever read. Not that the stories do not take Lovecraft’s worldview seriously. Quite the contrary. They take it so seriously as to border perilously—but never gratuitously—on the absurd. And in many senses, the absurd is closely akin to the horrific.

This pitch-perfect tone begins with the opening paragraph of John Ashmead’s introduction, with its absolutely straight-faced account of his attempts to access the seventeenth-century copy of the Necronomicon purportedly held at Harvard’s Weidener Library; and holds true through the ironic Biblical paraphrase that is the final line of Robert M. Price’s “The Bonfire of the Blasphemies.” Unlike many anthologies, in which one or two stories might not quite meet the standards set by the rest, Tales from the Miskatonic University Library is consistently entertaining and engaging.

Don Webb’s “Slowly Ticking Time Bomb” concentrates on a typically deadly volume, the Ool Athog Chronicles, an esoteric book of spells in five parts, in which pages are sometime blank…and sometimes disappear altogether. Reading each part makes possible the fulfillment of the reader’s wildest dreams; reading the final part leads to death.

Adrian Cole’s “The Third Movement” introduces the fantastically named Artavian Wormdark and his search for the infamous Malleus Tenebrarum at the request of a mysterious visitor known only as Vermillion. Unfortunately for Vermillion, he and his controllers, the Dark Army, are well known to Wormdark. And thus the trap is set.

Dirk Flinthart’s “To Be in Ulthar on a Summer Afternoon” is a marvelously light-tone piece detailing Bill Drake’s attempts to retrieve a copy of The Dream Journal of Arpan the Elder, overdue from the Special Collections of Miskatonic University and currently somewhere in the Dreamlands, where “not all dreams are desirable.” It is, in fact, a highly dangerous place but, well, the book is, after all, overdue.

Harry Turtledove’s “Interlibrary Loan” is a cautionary tale emphasizing the near-sacred nature of interlibrary cooperation. When Wilbur Armitage receives a request from a middle-eastern scholar to borrow the Necronomicon, he feels honor-bound to fill it, in spite of the current turmoil in the region and his misgivings about the courier sent to collect it. In the wrong hands, the volume would be a horrific weapon. As things turn out, Armitage is quite correct in his misgivings; on the other hand, he does know a thing or two about the book that the would-be terrorists do not.

Will Murray’s “A Trillion Young” posits the unthinkable: what would happen if, through some mind-numbing idiocy of the modern generation, the Necronomicon were digitized and released into the internet, triggering ramification of literally global dimensions.

A.C. Wise’s “The Paradox Collection” plays with contradictory realities when the newly appointed temporary Special Collections Assistant discovers the complexities of the aptly named Paradox Collection, where books—and people—simultaneously do and do not exist.

Marilyn “Mattie” Brahen’s “The Way to a Man’s Heart” deals with Lorelei Tuscarelli’s frustrations as the wife of a workaholic professor of Arcane Literature at Miskatonic University. Lonely and piqued by her husband’s apparent obliviousness to her sexual charms—to say nothing of her sexual needs—she goes to the library to see if she can find a way to combat her misery. A friendly librarian suggests something along the culinary lines…and recommends—what else?—The Gastronomicon: Recipes to Enchant and Enlighten Discerning Palates. The Shoggoth Soufflé sounds perfect for her needs.

Douglas Wynne’s “The White Door” presents The White Door, a book that “reveals a true account of the realms beyond death”—but that exists in but a single copy. But how does one search for a book capable of moving on its own from library to library?

P.D. Cacek’s “One Small Change” begins with a minor disturbance in reality: sixty-three-year-old librarian Eleanor McCormack notices that the wintering geese are flying north instead of south. And then the strange book arrives on interlibrary loan from the Miskatonic University Library…and the changes increase.

Alex Shvartsman’s “Recall Notice” consists of a series of letters, initially from Dr. Blain Armitage of the Miskatonic University to Mr. H.W.P. Lovecraft III, relating to the latter’s use of his great-great-grandfather’s century-old library card. Included among the books he is requested to return are the Necronomicon, along with its attendant Cliffs Notes and Dummies guides, a R’lyehian-English dictionary, and a Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue. The letters become more strident as Armitage discovers the extent to which the younger Lovecraft is to blame for “the immediate demise of the world!”

James Van Pelt’s “The Children’s Collection” takes place, not at Miskatonic, but in the Kingsport Public Library, where the narrator is beginning his first job as librarian for the Children’s Collection. Since the Kingsport facility functions as an extension of the Miskatonic library, a number of its books are a bit unusual. But then again, so are the children that he invites to a special, after-hours story hour.

Darrell Schweitzer’s “Not in the Card Catalog” covers thirty years of Nick Blackburn’s association with the Miskatonic University Library; its redoubtable head librarian, Mrs. Hoag; and the mysterious volume, The Book of Undying Hands: “older than time, older than mankind or this planet” and still being compiled, held shut—or perhaps waiting to be opened—by living hands.

Robert M. Price’s “The Bonfire of the Blasphemies” brings the anthology to an appropriate conclusion as, in the opening paragraph, the Miskatonic University’s Hoag Library—and in particular the Special Collections Room—are destroyed by fire, including the shelves of dangerous and dangerously seductive volumes. Ezra Pepperidge takes it upon himself to rebuild at least the fundamentals of the collection, scouring the world for replacements. And surprisingly succeeds, only to learn—as all do who meddle in such things—that there is a price to be paid.

From beginning to end, Tales from the Miskatonic University Library is a pleasure to read. The stories are fascinating; the characters—whether old friends with names such as Whately, Armitage, Bierce or Carter, or new friends who have much to learn about the universe—are fresh and engaging. There are moments of sheer fun, as when a would-be terrorist, determined to destroy the West, confronts a co-ed wearing a “Miskatonic University Fighting Cephalopods” T-shirt. Every story is well-conceived and well-constructed. Taken as a whole, Tales is worthy of the Lovecraft name and adds new levels of enjoyment to the Mythos.