Edited by Bill Campbell and Edward Austin Hall

Rosarium

ISBN 978-0989141147

October, 2013; $19.95 PB

Reviewed by K. H. Vaughan

In the introduction to Mothership, editors Bill Campbell and Edward Austin Hall describe their love of science fiction and the process of coming to terms with the absence of people of color in meaningful roles. One need look no further than the monolithic Whiteness of the Star Wars universe with its sinister Orientalist Trade Federation, Gungan minstrel show and lack of voice or official recognition for the Wookie sidekick at the end of Episode IV to see it. The state of SF today is not substantially better, films like The Matrix trilogy aside. It is an issue pervasive throughout speculative fiction. Fantasy continues to focus on mythological versions of Europe that are less ethnically diverse than Europe actually was, and minorities are most commonly exotic foreigners or orcs. Horror is also dominated by a majority male perspective. Minorities and women occupy a limited space, often relegated to villain status or specific non-threatening secondary roles. The half-life of the Black friend in most horror films is relatively short.

Even when there is some effort to change this, by writers who hold a more progressive view of the future and seek to do more than simple tokenism, the overall trend is to add color but in ways that carefully avoid issues of race. When a vision of the future is made color blind, it so often does so by glibly dismissing the issue: the post-racial future somehow has arrived, but as far as how that happened, the large body of SF is silent on the issue. It recalls South Park’s underpants gnomes: stage one, racism and sexism. Stage three, no racism and sexism. There are very few narratives that deal with the difficult transition process, except those displaced into human-alien relations and then either carefully controlled (Conquest of the Planet of the Apes was modified the studio after initial screenings to include a less violent and revolutionary ending) or revisionist/apologetic (the heroic White Male saving the indigenes as per Avatar).

When the post-racial future is presented in speculative fiction, if people of color even exist it is nearly always after assimilation into a culture built on the assumptions of contemporary neoliberalism. That is, the subtext almost always suggests that the color of your skin won’t matter in the future as long as everyone is on the same page culturally, with minor exceptions allowed for a hint of flavor. Aesthetic differences such as clothing and food preferences are embraced, as is the occasional cute accent or green sex partner, but meaningfully different perspectives and belief systems are nearly always relegated to alien species that are culturally primitive. You may be welcome as a person of color in the future, but only on terms that the majority can comfortably accept. The stories of Captains Janeway and Sisco are set well away from the cultural core and seat of power. Everyone will ultimately be assimilated, even if the process is less aggressive and intrusive than the Borg invasion.

Yes, there are exceptions. I can name many, but those anecdotes do nothing to counteract the overall historical trend. The base-rates are the base-rates, and the past and present are what they are.

Despite the ongoing ugly and public displays of vitriol and privilege on the internet around the proper place of women and writers of color in speculative fiction, I think there is evidence that we are on the edge of change whether people like it or not. It is not the case that writers of color haven’t been around, but their visibility and influence have been historically constrained. With the international reach of the internet and explosion in small presses, the playing field is tipping in a more inclusive direction, and anthologies by, about, and for people of color are becoming more common. The first that I am aware of (please note, I am not claiming expertise), Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora, (Sheree Renée Thomas, ed.) was released in 2000 and followed by Dark Matter: Reading the Bones in 2004. Since the publication of Dark Matter’s first volume, the pace of such publications has increased at an accelerated rate, including Mojo: Conjure Stories edited by Nalo Hopkinson (2003), So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan (2004), Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction edited by Grace L Dillon (2012), AfroSF edited by Ivor Hartmann (2012) and We See a Different Frontier: A Postcolonial Speculative Fiction Anthology edited by Fabio Fernandes and Djibril al-Ayad (2013). There are also a number of exciting titles slated for 2014 release (see my recent contribution to SF Signal’s Mind Meld). It suggests that, despite all the grumbling from some who seem to like their speculative fiction white and male, different voices and perspectives are increasingly available. The stories in Mothership reflect this general trend. It includes one reprint from 1978, but most of the reprinted stories date from the late 1990s onward, and about half of the pieces are newly published in this volume. Campbell and Hall have selected forty pieces from an impressive international group of writers. There is some flash fiction, but most appear to be in the 3000 – 5000 word range.

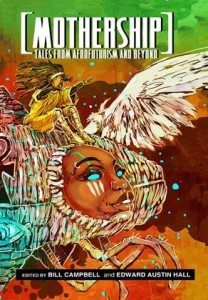

I would offer a note of caution for potential readers who may not know about Afrofuturism as a larger cultural movement. The cover art and introduction to Mothership explicitly evoke the science fiction genre. I confess I was expecting, based on these factors, more stories set in the future. Many, if not most, would be traditionally described as something other than SF: a mix of horror, fantasy, and magical realism. Afrofuturism is a broad cultural movement in music, art, and literature that can be difficult to pin down, and does not need to be defined by me. In a sense, that’s part of the point: it isn’t simply about Black people in spaceships, but a broader examination of the experience and perspective of people influenced by the African Diaspora and colonial legacies. It purposefully does not conform to the standard genre boundaries established by mainstream commercial publishing. The term may conjure visions of Afronauts, but the text itself seems designed to force the reader to not only question the role of race and ethnicity in speculative fiction, but to challenge the preconceptions and systems that shape writing as a process and industry. The aesthetic of the movement is anti-hegemonic and revisionist, and not just about getting a more representative sampling of faces in the same whitewashed stories. Does it matter if it conforms to expectations for what science fiction is? It might from a pure marketing standpoint. But the point for the reader who wants to see a diversity of perspectives is that the anthology shouldn’t conform to your expectations of what it should be. Then it would just be the same stories written by different people, not different stories. There is, however, a risk that some readers will have trouble adjusting when the content doesn’t seem to match their expectation set up by the cover and introduction. They should get over it and enjoy the work.

The stories in the anthology are of high quality overall, but when part of the goal is to open the door to a broad range of styles, you can expect that not all of them will resonate with you equally as a reader. But if a particular piece doesn’t, it won’t be because of bad writing. From a technical aspect, the writing is well-crafted throughout. In terms of the selection and arrangement of the table of contents, the editors are successful in varying the pace, length, and tone in order to keep the overall flow of the anthology smooth but interesting. It is a great read.

Ultimately, the volume introduced me to many writers I did not know, and a lot of narratives that don’t fit the standard model that dominates commercial science fiction in film, television, and publishing. I was honestly expecting more stories that would pull me out of my comfort zone or that pushed boundaries further, but it also gave me a lot to think about. I’ll take all the quality, thought-provoking speculative fiction I can get. Mothership is an unqualified success, both as an effort to promote writers of color and more diverse ideas of what speculative fiction is, and as an effort to edit a volume of great stories.

Fans of horror and dark fiction will find plenty of stories within this volume that will scratch that particular itch.