Hellnotes Interview

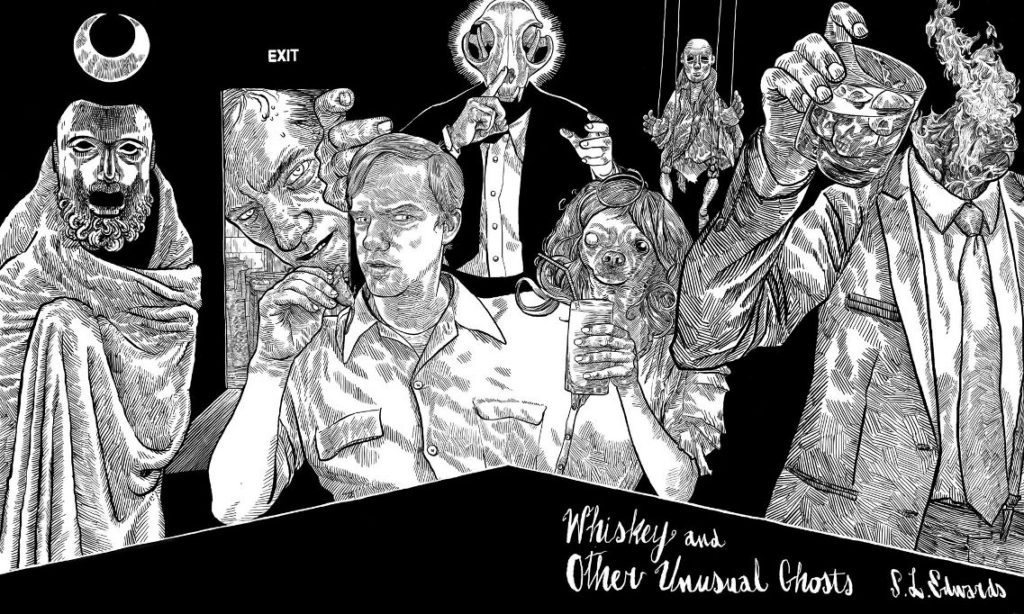

S.L. Edwards – Whiskey and Other Unusual Ghosts

Interviewed by Gordon B. White

S.L. Edwards is a rising star in the horror genre, and his debut collection Whisky and Other Unusual Ghosts (Gehnna & Hinnom, 2019) was released earlier this July. Today, he’s been kind enough to join us and talk about the difference between spirits and ghosts, why he’s drawn to insurgencies, and what big things he’s got planned for the future.

Hellnotes: First off, congratulations on your debut collection Whiskey and Other Unusual Ghosts! I know that you’ve been working on this for a while, so what’s it been like to see it finally come out? How has it been to watch the reaction?

S.L. Edwards: A few things first, before I get into all of that. (1) Thank you for having me on, Gordon. I’ve admired your writing since I read a story from you in Breath From the Sky. (2) Congratulations on your own collection “As Summer’s Mask Slips and Other Disruptions.” I know how hard it is to put a collection together and find a publisher, so I am absolutely thrilled to see your success.

Now, to be perfectly honest, it’s been a little emotionally overwhelming. I’ve been quite pleased with how the community has treated me. I’ve always tried to champion my peers and friends, and it seems people are returning the favor. Beyond the very generous people who wrote the blurbs, and Gwendolyn Kiste, who wrote the introduction, new readers have started to tell the authors sharing the book that they plan to pick it up. Some very famous writers have also shared the collection, too. Laird Barron shared the link, and that turned me into an energetic mess.

HN: How would you describe the stories contained in the collection? Many of our readers will be familiar with your work, but for those who aren’t, what can they expect in terms of tone and content?

SLE: Well, I wanted to give a sample of just about everything I do. The collection is more or less assembled based on length and theme. It starts off with a piece of original flash fiction, “Maggie Was A Monster,” and ends with the novelette “Whiskey and Memory.” I try to offer character-heavy fiction, and if I did my job right you’re going to care about the characters before you leave them. And, furthermore, it should hurt to leave them.

HN: The collection has an evocative title: Whiskey and Other Unusual Ghosts. The punster in me has to ask, though, why not “Other Unusual Spirits”?

SLE: You know, I had the title in mind for quite some time, and it wasn’t until I found a publisher in Gehenna and Hinnom Books (hi Charles!) that the pun even occurred to me. But, I do have an answer, because I could have changed the title.

To begin, despite my reputation as a funny person, the collection itself is not very humorous. The tone of most of these stories is quite somber, if not downright depressing. There’s a lot of truth to these stories, in that these are things that figure into our lives and our imaginations. Addiction, violence, war. And it wouldn’t be right to laugh at these.

Furthermore, I think “spirit” has a different connotation than “ghost.” Spirits can be benign. They can bless you. They can surround you. They can safeguard and protect you. When I hear the word “spirit” I tend to think of warmth, comfort.

I don’t think of that when I hear “ghost.” When I hear “ghost” I think of something which has violated the natural order. A presence that does not belong, and is very rarely benevolent. And ultimately, that’s what these things are. No one begins life wanting to fall into addiction. Into violence. I’m not someone who really believes that these things are the natural order. Rather, they are major disruptions. So that is why “Whiskey,” this liquor with cultural connotations of both high and low society, is an “unusual ghost.”

HN: I won’t ask you to name a favorite story (although freel free to do so!), but instead I’ll ask you if there’s one story that you’re particularly pleased to see collected so that it can reach a new audience?

SLE: I always change my answer on this question. It usually comes down to a toss-up between “Volver Al Monte” and “Cabras.” The two stories share a lot. Both deal with fathers and daughters. Both deal with the aftermath of civil wars. Manuel of “Cabras” is an old, retired communist guerilla dealing with a bunch of upstart wannabe rebels, these city boys heading for the jungle and trying to undertake a level of violence that they really don’t seem prepared for. General Alfonsín Santos is likewise an older man. But he was…well, a “militarist” is I suppose the correct word. He doesn’t really have an ideology beyond the blanket “far-right” descriptor of so many generally apolitical armed actors.

I’m eager for those stories to be out there, so readers can compare and contrast them. Together, I hope they offer a very dynamic picture of political violence and internal conflicts. I hope the differences shine through, because they were deliberate. “Volver” is very much the thematic sequel to “Cabras.” There’s a reason General Santos talks and Manuel doesn’t. There’s a significance there, though I don’t want to ruin that for readers who might bring their own interpretation to these stories.

“The Case of Yuri Zaystev” remains a favorite of mine, too. I’ve studied the Stalin regime quite extensively, and it’s always a heavy subject to return to. “Maggie Was A Monster” is a very personal story too. “Whiskey and Memory” is one that I am also eager to share, as it’s a previously unpublished piece and one of the oldest in the collection. “And the Woman Loved Her Cats” has been something of a crowd pleaser too. “I’ve Been Here A Very Long Time” is another, because that was published in a very limited run.

HN: Each story contains an Author’s Note at the end, which provides some context and insight into your creative process. What was it like to revisit these stories to prepare these notes? Were there any stories that were more difficult to annotate than others? Were there any where your thoughts about them now are particularly different than how you felt about them when they were fresh?

SLE: If you’ll let me answer this one a bit out of order: yes. There was one in particular that was quite difficult to annotate, and there’s a reason that the annotation is so brief. I wrote “Maggie Was A Monster” when someone very close to me was struggling with addiction. I had become heartbroken, because I had done at the time what I viewed to be everything possible to try and help them. Looking back now, I realize that wasn’t true. I was rightfully angry, rightfully hurt: but I will always regret not trying to push forward.

The good news is that this person is now thriving. I look at them, and honestly I cannot think of anyone I am prouder of. I love them, and think they are so incredibly strong for overcoming that demon. There was a lot of hesitation in including “Maggie” for these reasons, because so much had happened between when it was written and when it was included. I look at “Maggie” now, and it feels more like a true horror story than something biographical. A cautionary fable, which is why I ultimately decided to keep it in.

The rest of the stories were quite fun to revisit. There’s something to be said for author’s notes. My favorite writers do them, and I wanted to offer it for readers.

HN: Here and there, readers can see some of your historic influences surface — “Golden Girl,” for instance, involves a puppet evocative of R.W. Chambers’s King in Yellow, while “Movie Magic” is a love letter to horror cinema. You don’t work in pastiche, however, and you don’t appear to explicitly invoke other mythos. Where do you see your own influences shining through in these stories, both the “classics” and any specific contemporaries? Are there any particular sources that other people see in your work, but that come as a surprise to you?

SLE: I’ve talked quite a bit about my Russian literature influences. Bulgakov’s “Master and Margherita” has a reference in “The Woman Loved Her Cats.” Tolstoy and Vassily Grossman get their nods in other stories. Then of course, Gabriel García Marquez.

I think, in terms of horror influences, it’s hard for anyone in weird fiction to fully escape the shade of H.P. Lovecraft. The man had a way of invoking terror that no one else really can rival in view, so I do see some of Lovecraft’s prosaic techniques snaking their way in. Charles (P. Dunphey) said that “We Will Take Half” reminded him a bit of Arthur Machen. “The Case of Yuri Zaystev” was partly inspired by Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows.”

And in terms of contemporaries…you know, there are a lot of writers who I admire but I’m not sure it would be proper to say I take any direct inspiration from them. John Paul Fitch, who is a great writer and a great friend, complimented me by saying that “Volver Al Monte” reminded him of a Laird Barron story. While I took that as a huge compliment, I’m not sure that I wrote it with Barron in mind. Certainly he has done more than his fair share of work on hardened soldiers, but I didn’t even have that in my head when I was writing. Other folks have been kind to compare me to Nadia Bulkin, who is a friend and an absolute luminary in the field. But she’s way better than me.

HN: Speaking of contemporary writers, it’s become a cliche to say, but we really are living in a fantastic time for lovers of horror and Weird fiction. Elsewhere you’ve talked about which currently working writers you admire, so we won’t rehash that. Instead, are there any particular upcoming releases that you’re especially anticipating?

SLE: This year is going to be a damn strong one for story collections. I am really looking forward to Betty Rocksteady’s debut collection, In Dreams We Rot. No offense to everyone else, but Betty is a writer who I’ve wanted a short story collection from since forever. Scott R Jones is another writer who is at the top of that list, and his collection Shout Kill Reveal Repeat looks great. I haven’t read any Matt Cardin, because his stuff is a little bit harder to find, so I’m looking forward to reading To Rouse Leviathan. John S. McFarland is a newer writer, also from the same stable of writers in Gehenna and Hinnom as I am, and I’m looking forward to reading his debut collection The Dark Walk Forward. Laura Mauro is a new friend, who shares my love of Game of Thrones character Stannis Baratheon. That is reason enough for me to want to buy her collection Sing Your Sadness Deep.

So already, you can see 2019 is going to be something of a powerhouse year for story collections. There are a few things I need to go back and read: Nathan Ballingrud’s Wounds. Brian Evenson’s Song for Unraveling the World. Farah Rose Smith’s One of Pure Will. Then we have John Langan’s Sefira and Other Betrayals. And there’s a Jeffery Thomas collection coming out from Worde Horde later this year, The Unnamed Country. And of course, the grand shrimp-rater himself, Peter Rawlik, had his collection Strange Company drop the month before mine.

So there you have it. I am confident that these eleven collections will be making next year’s award circuits. The Stokers, the Shirley Jacksons. I want to be able to promote these good people as knowledgeably as possible, and encourage readers to do the same!

HN: There seem to be a few recurring elements in the stories here in Whiskey. One noticeable area that keeps cropping up is war and its pervasive effects. We see the toll it takes on the soldiers in “When the Trees Sing,” the larger society in “We Will Take Half,” and the future generations in “Cabras.” All of this destruction, on scales both intimate and grand, ties together in “Volver Al Monte,” which – perhaps not coincidentally – is one of my personal favorites in the collection. What is it about this particular theme that keeps drawing you back to it, circling it in new ways? Do you have a personal connection to this, or is it a reflection of the world we live in?

SLE: Early on, I decided that the most effective way to write horror was to write about things that scare me. And war, particularly civil war, scares me to death. I don’t think there is anything natural about it. So many fail-safes have to break. States need to retreat, things need to become so dire that armed bands arise for self-protection. Grievances need to run deep enough that teenagers pick up guns and go to war. That’s nightmarish, and sometimes it seems unending.

I research civil wars in my day job. So to answer the second and third part of your question, it is both a personal (academic) connection and a reflection of the world we live. But I would caution readers: people are messy and contradictory, and I am no exception. I am both a self-styled “realist” and a self-styled “optimist.” I can quote Thomas Hobbes, but don’t quite buy that the natural state of mankind is war. I actually think that’s a rather naïve assessment of what people are capable of.

When writing about war, it’s important that readers get the sense that this is not a place for heroes. Like you say, there’s not particularly a clear good and evil. None of the “protagonists” in these war stories are “heroic” by ANY generous definition. General Santos sort of admits to being motivated to extreme brutality not by any hate, but due to a desire for efficiency and stability. Manuel seemed to believe in a struggle at one point, but then he lived it. And living that kind of fight is hard.

And the main character of “When the Trees Sing.” Woof. If readers have ANY sympathy for that man (and they’re supposed to) I recommend they look up the laundry list of abuses committed by “Tiger Force” soldiers.

These were hard stories to write, and because they were hard to write they forced quite the reaction in me. And it shows. They were agonizing to write and are agonizing to read. That gives me some hope that readers will agree with me.

HN: Readers will also note that a number of these stories involve Latin American conflicts between the state and uprising forces, although you resist the urge to portray one side as definitively good and the other definitively evil. What draws you to this particular milieu? Do you find that an interest in this area drives your stories towards certain themes and ideas, or do you find that your thematic interests push you towards this setting?

SLE: Well first, the disclaimer I always try to give: I am a straight, twenty-something white guy from suburban Texas. I want to write about these places, and to do so in a way that is not exploitive. To that end, I try to take inspiration from historical settings, but don’t name any in particular. For instance, the “Tuta Puriq” of “Volver Al Monte” are absolutely inspired by the very real and very terrifying “Sendero Luminoso” insurgency of Peru. In “Cabras” there is some nod to a long, generational civil war that makes reference to a dynasty. That was inspired by the Somozas in Nicaragua.

And again, part of this interest is academic and part of it is personal. I grew up in a nearly bilingual part of North Texas. I was “raised” by my best friend’s family for a good half of my life. I never really felt like an outsider in that particular subset of “North Texan Mexican” culture. And then I lived in Costa Rica for a while, which I used as a launch pad to travel to other Central American countries.

I will also say that it is not that Latin America is a particularly violent place. That’s not why I write about it. Quite the contrary: this a very large, very diverse area of the globe. There is so much cultural difference within Latin America. But it also happens to be home to some of the most breath-taking nature, the kindest people and most vibrant ways of life. Nations like Brazil, Costa Rica, Colombia, they’ve been able to accomplish some truly amazing things which the United States never has and probably never will. Costa Rica, for instance, is one of two nations with no military. The other? Panama.

So to readers who might justifiably be concerned about a white author using the Latin American setting to invoke some strange “otherness”: I hope that I sufficiently conveyed here that I don’t consider this setting to be “other” at all. Earlier, I said what I find horrifying about war is that it’s a disruption. That I don’t think it’s natural. I certainly think that certain Latin American conflicts are just heartbreakingly tragic, and extremely avoidable. And furthermore, I think citizens and governments alike have made great strides towards ending these conflicts. I could talk forever about this subject, but we’d be getting into La Violencia, the FARC insurgency, Oscar Arias and his role in negotiating the end of the Central American crisis. Rómulo Bentancourt, a former Venezuelan President who I think was one of the most brilliant politicians (albeit an imperfect one) to ever live in the Western Hemisphere. Jose Figueres Ferrer, who told off both Richard Nixon and Fidel Castro.

HN: Beyond war, a number of stories in Whiskey address serious themes like addiction (“Maggie Was a Monster”), neglect (“I’ve Been Here a Very Long Time”), and complicity (“The Case of Yuri Zaystev”), usually through a lens of how that changes a person’s identity. Yet there are also some fun, almost pulpy horror stories in “Movie Magic,” “And the Woman Loved Her Cats,” and the delightfully twisted “A Certain Shade.” Since you cover such broad areas, let me ask: what do you think makes a good horror story? Do you prefer entertainment or a gut punch, or both? Since horror can do so much, is there an essential element to horror, or is that too reductive?

SLE: In my view, the best horror is recognizable. It’s not so abstract that it’s unrelatable. You’re right that these themes are serious, but they are also “mundane.” Even those of us who have very blessed, very charmed lives have encountered these things.

I would say that in my best stories, one could remove the supernatural element and still be left with a horror story. If we take away the monster for “I’ve Been Here A Very Long Time,” we still have a story about domestic violence. If we remove the fantastic elements of “Maggie,” we are still left with the story of someone ruining their lives.

In that sense, I would prioritize the gut punch over entertainment. Horror is a bit of a masochistic exercise anyway. The entertainment should come with the hurt. And what’s worse still, you’re supposed to like it. You freak.

But you’re right. Some stories in this collection are just fun for fun’s sake. And I think that’s okay. Writers owe it to themselves to have fun. Readers too. But if you’re going to write to entertain, you should lean into that pretty hard. Your concept should be pretty original, it should make people laugh, and if it doesn’t you’re going to be left with something that looks a lot like a Robert Bloch pastiche. And you can’t be Robert Bloch. There was already a Robert Bloch!

HN: If I’m not mistaken, you’re also in the process of putting together a second collection! What can we expect from that one? Is there a different flavor to the themes or styles, or is it a second shot of Whiskey?

SLE: Aha! So, you’ve sequenced the questions perfectly! “The Death of An Author” is all my pulpy, fun horror stories to date. It deals more directly with other authors’ playgrounds. There’s a Dracula story, another vampire story. Some Lovecraft/mythos tales, and even a King in Yellow one. They’re more fantasy/dark fantasy than “horror” stories. And while I like those stories a lot, they weren’t fit for “Whiskey,” which was all gut punches. “The Death of An Author” is very much entertainment for its own sake, and me leaning into fun-for-fun. It’s currently being go-fund-me’d, so please (dear readers) consider helping an author out.

But I do have another collection assembled, and I’m waiting it to send it off to a publisher who I’ve been courting for a while. “Monsters of the Sea and Sky” is about “conspiracies.” Not conspiracies in the “earth is flat” sense, but in normal things that happen every day. Family secrets. Hidden massacres. The latter half of the collection is all shared universe, set in the fictional nation of “Antioch,” which is a mix of Victorian England, Weimar Republic, and pre La Violencia Colombia.

HN: Finally, what’s coming up next for you? Beyond the concrete projects and releases, what sort of new and nebulous territories are you looking forward to exploring?

SLE: Well, I’m trying to work on some weird westerns, but I also finally have a novel idea. And I think that’s going to be where I have to go next. It will also be set in Antioch, and deal with the destruction of a family on the eve of national collapse. Curious readers should imagine “The Shining” on the eve of September 11, 1973 (the day of the Pinochet Coup in Chile). I’m returning to my Tolstoy, particularly Anna Karenina, to help map out these poor characters and what is going to happen to them.

- L. Edwards is a Texan currently residing abroad in California. He enjoys dark poetry, dark fiction and darker beer.

https://www.facebook.com/SLEdwardswriter

https://www.amazon.com/S.-L.-Edwards/e/B01M34MZOT