Official Author Rendering

Hellnotes: Congratulations on your new collection Guignol & Other Sardonic Tales! Although this is your third short fiction collection, some of our readers may not be familiar with your work yet. For those newcomers, could you tell us a little bit about yourself, what kind of horror you write, and how you started writing fiction?

Orrin Grey: I like to think of what I write as “fun horror.” Because that’s what horror has always been for me, something fun. At least as a writer, I’ve always been more attracted to the “pleasing terror” of M.R. James or E.F. Benson than more visceral or gruesome stuff. Not necessarily as an escape, per se, but nevertheless as a place where I felt comfortable. I struggle with anxiety, and maybe inhabiting the liminal spaces of horror fiction made me feel safer in the often uncertain and cacophonous real world. Or maybe I just like monsters. Whatever the case, horror is the genre that I love, and I want that love to show through in my writing.

That said, the stories in Guignol are probably among the grimmest I have ever written, though hopefully they’re not still without their fun, too. When it comes to how I approach horror fiction, I always think about a description I once read of the British ghost story writer Robert Westall that said, “It was the infinite strangeness of the supernatural that fascinated Robert Westall, not the horror.” That’s always kind of how I’ve thought of myself and my own pull toward darker fiction.

HN: In Guignol’s Afterword, you mention that “[t]hese stories range farther afield than any [you] have collected before.” Indeed, I was pleasantly surprised to find that beyond tales in near-contemporary settings, Guignol offers an Industrial-era monster story, a roadhouse in 1920s Kansas City, a post-apocalyptic fairytale, and a sword-and-sorcery Choose Your Own Adventure, just to name a few departures. Is there a particular reason why, at this stage in your writing life, you find yourself experimenting more instead of settling into a comfortable style? Is it a conscious effort to push your boundaries, or is it some other kind of a gravitational pull?

OG: Part of it is definitely feeling more confident. I can take chances that I didn’t feel like I could take earlier in my career and still expect to turn out a story that’s good enough for publication. But part of it is also the realities of how I write these days. Most of the stories in Guignol were written in response to invitations to contribute to themed anthologies, and those themes, in many cases, pushed me outside the bounds of my usual comfort zone, both forcing me to experiment and freeing me up to do so.

HN: While I try never to ask if an author has a “favorite” story in a collection, are there one or two that you are pleased will now get a chance to find a larger audience? Furthermore, while your Afterword in Guignol suggest that you don’t necessarily approach your stories as a way of “channeling your pain into writing,” in hindsight you can see how traumas you were processing nevertheless made their way into some of the stories. To that end, were any of these stories particularly difficult to write? Was there a catharsis that came with finishing them?

OG: While of course I’m obliged to say that I like all of the stories in Guignol, I’m really eager to see how people react to “A Circle That Ever Returneth In.” I’ll avoid getting too much into why, as that might somewhat spoil the fun for readers who haven’t gotten a chance to look at it yet, but I’m very pleased to be getting it more out into the world. I’m also happy that more people will get a chance to read “Dream House,” the story that opens the collection, mostly just because I had a lot of fun writing it.

There are definitely stories in Guignol that were difficult to write, but more often it was particular scenes or moments that were painful. “When a Beast Looks Up at the Stars” was probably the most emotionally trying, though there were tough spots in more than a few of the others. I think there was some catharsis that came from writing individual stories, but, funnily enough, I think more came as I was putting this collection together and writing up the author’s notes.

HN: Guignol includes “Author’s Notes” about each story, which many readers (including me) enjoy reading. In a few of these Notes, though, you mention that the story you wrote isn’t the story you expected to write at the outset (for example, “Haruspicate or Scry” or “Deep and Dark”). How does that fit in with your normal writing process? Is your normal writing very intuitive and surprising, or do you tend to plan out your stories before drafting?

OG: The best metaphor I’ve ever come up with for how my normal writing process works is a video game called Katamari Damacy. Many readers will probably remember the game, but for those who don’t, in Katamari Damacy you roll around a giant ball which picks up just about anything that it has rolled over. Once it has accumulated enough stuff, it turns into a star.

So, my usual writing process is to get one idea—one part of a story, often the central phenomenon, but not always—and then roll it around in all the junk that has collected in my brain. Movies, books I’ve read, other story ideas, things that have happened to me, and so on. When the idea rolls over something that seems to fit with it, it picks it up, and once it has accumulated enough bits that seem to work together, I can usually hammer the resulting mass into a story.

Of course, as I’ve been a freelance writer for the last few years, I’ve had to adapt that process considerably, because the Katamari approach doesn’t lend itself well to either deadlines or the work-on-demand nature of freelancing. So, I’ve learned how to write lots of other ways. When I was writing my licensed novel Godless for Privateer Press, for example, I was working off an incredibly detailed, 9,000 word outline that was provided for me by the client.

In the case of the stories you mentioned, the situation was once again that I was invited to submit to a themed anthology. In both cases, the theme was one that I was particularly passionate about: monsters and talking boards. I suppose that I expected to write somewhat more boisterous tales for subjects that I was so keen to write about, but I ended up telling more contemplative and less openly pulpy stories in both cases, simply because that’s what I was able to put together by the deadline with the bits that were available in my brain at the time.

HN: One aspect of your style that always impresses me is the verisimilitude of the details. In particular, your “real world” stories weave in brand-name items, actual movies or shows, and historical events that do a lot of work to establish a setting which grounds and, in turn, enriches the speculative elements. For example, the gas station offerings of Mountain Dew and Street Fighter II lends believability to an otherwise otherworldly arcade game in “Invaders of Gla’aki,” while references to actual films and film history provide atmosphere to “Dream House,” “Baron Von Werewolf Presents …,”“The Cult of Headless Men,” and others. Is this saturation of concrete, real-life detail a conscious part of your style, or is it more of a byproduct of how you view the world? Do you have any particular influences related to these stylistic elements of your fiction?

OG: Part of the answer to this question is that Katamari approach to story creation that I mentioned in the question above, and at one time that may have been all there was to it, but over the years I’ve actually worked pretty hard to intentionally refine this technique. Some of that is because I realized that I could get away with it. I tend to think in terms of an endless series of refracted references to various things. In my head, almost everything is a string of interpretations, inspirations, and conversations with all the other media that I’ve ever imbibed. What Gemma Files calls “garburator imaginations” in her introduction to the book.

I think that when “Persistence of Vision,” a story of mine that’s in Painted Monsters, got reprinted in Ellen Datlow’s Best Horror of the Year, I sort of had this epiphany that, hey, not only are people going to let me get away with writing stories that read the way my mind works, they might actually really like them.

It’s more than that, though, too. There are plenty of movies or books that simply name-drop other movies and books, but I try to let my references do more than simply act as Easter eggs. Guillermo del Toro talks a lot about how his movies are filled with “eye protein” rather than eye candy—visual storytelling that transmits every bit as much information about the characters and the plot as the screenplay does, coded into shapes and colors and staging and repeated motifs—and I try to use my references to familiar (or unfamiliar) real-world elements to do a similar kind of heavy lifting, adding resonance and atmosphere and allowing me to expand the world I’m building through association, hopefully taking it to places it couldn’t otherwise reach.

HN: You have a bit of reputation for taking story ideas from unlikely sources (the title story “Guignol” and “Baron Von Werewolf Presents Frankenstein Against the Phantom Planet” offering just two examples). More than merely finding an unusual seed, however, your work combines and remixes these ideas and horror tropes to create stories that are exciting and new, even while retaining a touchstone in the familiar. The term “Frankenstein” could be used to describe this combination of elements, but I think of them more as “chimeras” — rather than feeling stitched together and jolted into life, these disparate elements operate together in an organic, living way. Is this work of combining and mixing elements an intentional part of your creative process, or is it more intuitive? What do you find to be the most disparate elements you’ve created a story out of? Were there any combinations that you wanted to try but just haven’t been able to get to work?

OG: As above, this question is at least partly answered by my Katamari-ish approach to story creation, but again, it’s also something that I actively strive to do, though it probably wasn’t at first. At first, I’m sure, I just wanted to write the kinds of stories that I liked, and, as time went one, I began to find, and refine, what elements the kinds of stories I liked had in common, and that was often this chimera (I like that) of disparate genre ingredients.

That chimerical bent is present in some of my earliest literary influences such as Roger Zelazny and Clive Barker, and it also comes, in part, from growing up reading comic books, which tend to jam together all manner of disparate genre elements into a single, often uncomfortably shared universe. But the biggest breakthrough for me came in the form of Mike Mignola’s work on Hellboy. One of my favorite quotes about the creative process comes from Alan Moore’s introduction to the second Hellboy trade in which he says, “the trick, the skill entailed in this delightful necromantic conjuring of things gone by is not, as might be thought, in crafting work as good as the work that inspired it really was, but in the more demanding task of crafting work as good as everyone remembers the original as being.” That’s what I’m always at least trying to do.

When I was a kid, my school library had these Crestwood House monster books, with black-and-white movie stills from the classic monster movies of the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. I’d never seen those movies, but I used to pore over those books, staring hard at the stills and trying to imagine the movie that they came from. I think a lot of what I’m trying to accomplish when I sit down to write can be summarized by saying that I’m still trying to write those stories.

It’s difficult for me to really say what the most disparate elements I’ve ever crafted a story out of were, because to me they’re never disparate anymore by the time I’m making a story out of them. I’ve found the ways they fit together, at least in my mind. But I know that there are definitely still elements that I want to work into stories and haven’t managed to yet. I’m a huge fan of fungal horror, so much so that I co-edited an anthology of fungal fiction with Silvia Moreno-Garcia, but while fungal horror creeps in at the edges of several of the stories in Guignol, I’ve never yet managed to write a head-on fungal horror story myself. Part of what keeps me writing is that there’s a seemingly limitless pantheon of things that I still want to write about, if I can just get that Katamari ball to roll over the right stuff at the right time…

HN: Sort of along those lines, another fascinating aspect to some of these stories is the seeming transparency of influences. As illustrations, many older films are name-checked, the King in Yellow makes an appearance(s), and a couple of pieces have overt tarot imagery. However, in your notes to “Invaders of Gla’aki,” you say that despite publishing in a number of Lovecraftian-themed anthologies, you go out of your way not to put in overt references to Cthulhu, Miskatonic University, and other Mythos elements. Is there a reason that you steer away from explicitly referencing that particular area? What kind of balancing act do you see between honoring your influences and developing your own creative works?

OG: I try to always wear my influences on my sleeve. Partly that’s just who I am—I’m enthusiastic about the things I like, and I want to share them with everybody—and partly it’s because that’s how I developed as a writer, by following other people who were willing to be open about their influences. I mentioned Mike Mignola above, and he’s probably the biggest figure in my personal pantheon, and through his work I discovered countless other writers, artists, movies, etc. that have become huge influences on me. The same goes for Guillermo del Toro. I like most of his films, of course, but I love his commentary tracks, which are filled with his influences, and always worth the price of admission all by themselves.

But while I want my influences to be as transparent as possible, I also always want to be playing in my own sandbox. That’s part of why I try to avoid overt references to Lovecraft’s Mythos. At this point, there is a cottage industry in writing Lovecraftian pastiches of one stripe or another, and some people do an amazing job of it, but I’d rather take those influences and make something of my own, the same way that Mignola was obviously influenced by Lovecraft (and others) but made his own thing in Hellboy’s complex cosmology.

Then there’s the fact that, because I so often incorporate my influences as overt references into my stories, most of my stories take place in a world where Lovecraft’s stories exist as stories, where they’ve been made into films, where, if we’re in the present day, you can probably buy Cthulhu slippers at a nearby store, so that changes how I incorporate Mythos elements into my stories. (You see a bit of that in “Dream House,” which takes place partly at the H.P. Lovecraft Film Festival in Portland.)

In the story that I wrote for Ellen Datlow’s Children of Lovecraft anthology, “Mortensen’s Muse,” I did something a little different yet. That story is a sort of take on “Pickman’s Model,” but is also based on the real-life relationship between photographer William Mortensen and classic scream queen Fay Wray. Because I was using fictionalized versions of both characters, I also used fictionalized versions of their movies, with titles shifted just slightly over to the left, though many readers will probably spot the references.

HN: Normally I would ask about themes and undercurrents in the stories, but Guignol’s Afterword already does a fine job of identifying and examining those. Instead, I was intrigued by your observation that when you put together your collections, you find unintended thematic ties between the stories. Do you think that’s a process of collecting stories that were written during a similar period in your life? Or, since collections like this tend to draw from stories written across several years, is it that once you start assembling them, the combined thematic weight begins to pull in other stories with the same hidden spine? What’s it like to look back on a group of collected stories and see that you have, in fact, been circling a particular topic longer than you’d realized?

OG: There’s a quote from Edward Gorey, I can’t find it right now, but it’s something to the effect that, “If there isn’t something in a drawing that you didn’t intend, then it wasn’t worth drawing.” I feel that way about themes in my fiction. Some of the best feelings in my life have been when other people point out some theme in one of my stories that I hadn’t even realized was there, but once they point it out it’s impossible to ignore.

When it comes time to put together a collection like this, it’s always a matter of what stories to leave out and which ones to put in. I suppose I could simply collect stories in the order they were published and dump out a collection whenever I had enough, but I don’t think that would create a book that was nearly as satisfying, and I don’t think very many writers do that. So, part of the process, when it comes to collecting stories, is finding those themes that cut across your work, and the ways that different stories bring out things in one another when you put them side-by-side.

As a reader, my favorite kind of book is the single author collection, so I’m always very happy when I get to put one out. And part of the reason I love those kinds of books so much is because of the ways that the different stories play off each other. When I was putting together Guignol, for example, I hadn’t originally included “Dream House.” In its place was an older story, “The House of Mars,” and the table of contents was in a different order. My wife, who is always my first reader on everything I do, looked over the manuscript and told me that “The House of Mars” didn’t fit. We talked over why, replaced it with “Dream House” and re-ordered the TOC, and everything felt much more satisfying. “The House of Mars” will go into some future collection, once I find the place where it belongs.

HN: Finally, what’s do you have on the horizon? Beyond the concrete, can you give us a hint as to any new interests or ideas that you’re just beginning to explore?

OG: Well, at the same time that I was finishing up Guignol I was actually working on several stories that are part of a linked story-cycle. Most of them don’t share characters or settings, but they all take place in the past, present, and future of the same “world,” or more accurately the same version of this world, and they involve hollow earth theory, the dreamlands, the nature of time, and so on. And, of course, lots of monsters.

A couple of these stories have already seen print in Cthonic: Weird Tales of Inner Earth and Lost Highways: Dark Fictions from the Road, and as I was working on the stories in the cycle, I realized that a few of my older stories were actually part of the same “universe” without my noticing it, so my stories “The Insectivore” in Cthulhu Fhtagn! and “New and Strangely Bodied” in For Mortal Things Unsung are both part of this same series. Several others are in press and can hopefully be announced soon, and I’m planning to finish up an anchor novella and eventually collect the whole “cycle” into a book sometime before too long.

As I type this, I’m coming out of a really tough year. The last twelve months have seen a blizzard of health problems hit my household the likes of which we’ve never seen before, and so a part of what I’m up to right now is trying to reorient myself and get my bearings. Which, to some extent, means remind myself of what I’m trying to do when I sit down and write. When you freelance for a living, it can be all-too-easy to get caught up in the sort of “daily grind” of doing the work, and forget the big picture of what you’re trying to accomplish with it.

To that end, I’m still writing some stories that deal heavily with film, but I’m trying out some approaches that are different than what I’ve written before, exploring the experience of watching or making movies, the places where we watch them, etc. A few of those have already seen print, including “Mortensen’s Muse,” which I mentioned above, and “The Granfalloon,” which was just reprinted in the latest volume of Ellen’s Best Horror of the Year. I hope there are more to come.

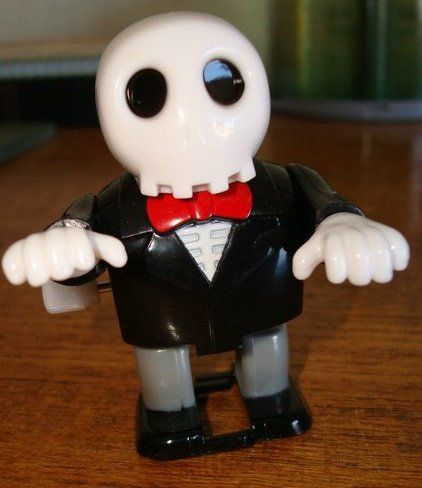

Orrin Grey is a skeleton who likes monsters, as well as a writer, editor, and amateur film scholar who was born on the night before Halloween. His stories of ghosts, monsters, and sometimes the ghosts of monsters have appeared in dozens of anthologies, and his essays on horror cinema have appeared lots of places, too.

Website: https://orringrey.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/greyorrin

Twitter: @orringrey