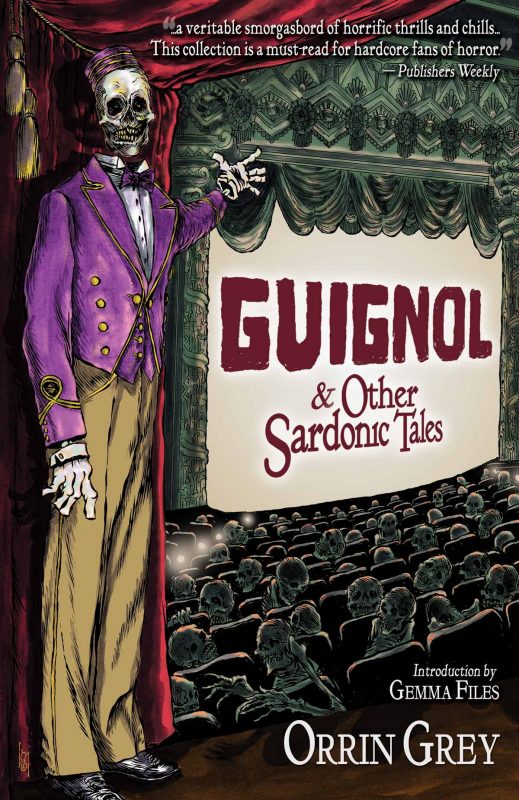

Guignol & Other Sardonic Tales

Orrin Grey

Word Horde

October, 2018

Reviewed by Gordon B. White

Orrin Grey’s third collection of short fiction, Guignol & Other Sardonic Tales, collects fourteen tales that capture some of his best, albeit darkest, work to date. Grey is a master of recombining tropes and remixing old ideas into fresh, electric combinations, and Guignol features these in spades while also stretching into strange and surprising new areas. Compulsively readable and by turns frightening, mournful, and just downright entertaining, this collection is highly recommended for all readers of horror.

Grey has cultivated a reputation for his unique and surprising combinations of horror tropes and sources. This collection, however, sees Grey both working like a champ in those areas that readers have come to anticipate, while still pushing his creative boundaries in exciting directions. For example, readers familiar with Grey’s earlier work likely expect recombinations of old horror movie tropes with new ideas, and, indeed, those stories are here in the lost stop-motion film of “Baron von Werewolf Presents: Frankenstein Against the Phantom Planet” or the Hammer horror meets fusty colonial anthropology of “The Cult of Headless Men,” just to name a few. However, this collection also presents wonderful mash-ups outside of old horror mainstays, such as the Industrialization-era chimney sweeps vs. monsters of “Shadders,” a 1920s Kansas City roadhouse where jazz summons demons in “The Lesser Keys,” and the cursed arcade cabinet of “Invaders of Gla’aki.” Moreover, Grey also explores settings that leave the “real” world behind, turning in delights like the Choose Your Own Adventure sword-and-sorcery cosmic horror of “A Circle That Ever Returneth In” or the post-apocalyptic fairy tale of “The Blue Light.”

While most of the stories collected here could be expressed as high concept ideas, it is Grey’s outstanding execution on those promises that makes this collection stand out. Each story creates a world where the strange and seemingly disparate ideas not only merge seamlessly, but seem inevitable. While it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly about Grey’s writing makes this possible, the answer perhaps lies in his consistent use of the ideal narrative voice. Whether in third-, first-, or even the quick foray into second-person, Grey shifts between narrators with an almost imperceptible ease. The key to these voice selections and their contributions to the reader’s immersion is not in overt tonal changes — indeed, find a similar, shared sardonic tone to most (to reference Guignol’s full title) — but instead in the details that each observes. The stories move at an engaging pace, but the narrators add just enough vivid background details and aside observations that the stories feel both conversations and vital. While they aren’t “real,” they are consistently and believably unreal.

Further contributing to the success of these tales is that Grey’s writing is always crystal clear. Whether building hallucinatory new worlds like the candy-colored Phantom Planet (“Baron Werewolf Presents…”), describing the non-existent lost episodes of an old TV show (“Dream House”), or repurposing elements drawn from his youth (“When a Beast Looks at the Stars”), Grey’s prose is vivid and detailed without becoming over-encumbered. While speculative stories are sometimes carried by the strength of the ideas more than the strength of the writing itself, it’s energizing to see Grey’s precision in both areas.

While these expertly done embellishments make all the stories engaging, if there is a nitpick here it is that a few tales which hew closer to classical story structures seem a little quaint. As a result, while the moment to moment reading those few tales is still immensely enjoyable, the final results are merely the sum of their (excellent) parts. For example, “Programmed to Receive” and “The Wheel and the Well” feel tonally and structurally akin, but where the former excels by taking an anarchic twist that leads to an unexpected ending, the latter (although filled with haunting details) charts pretty much the course readers would expect. Similarly, the spiritual debunking of “Haruspicate or Scry” stands out because of the richness of the characters and the grad student slice of life details, not because of the resolution that becomes obvious about halfway through. Still, these are minor quibbles and even when leaning on traditional story forms, Grey’s expert evocations of character and place through his choice of unique details makes them all a pleasure to read.

For those interested in a deeper look into Grey’s creative process, Guignol also contains Author’s Notes for each story and a thoughtful Afterword from the author. Although some readers may always prefer not to look behind the curtains, for an author with inspirations as widely disparate as Grey’s, these insights are a delight. From educational (Who knew that King Kong’s director wanted a sequel where the ape fought Frankenstein’s monster? Orrin Grey knew.) to emotional (discussing the personal roots and traumas that informed some stories), the information contained here can send readers out into the world or into themselves. These helpful and generous contributions from Grey enrich what came before without overshadowing.

In Guignol & Other Sardonic Stories, Orrin Grey offers readers a collection of perfectly polished mutations that twist familiar tropes and reader expectations to exciting new ends. As both a refinement of Grey’s previous stellar work and a departure point into stranger and darker fields than before, Guignol is a treat for horror lovers of every stripe.