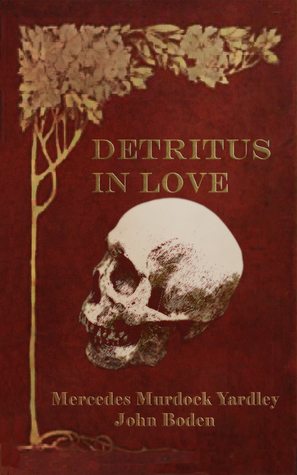

Detritus in Love

Mercedes M. Yardley and John Boden

Omnium Gatherum, eBook

October 3, 2016

Reviewed by William Grabowski

It might be a case of projecting inner disappointment onto the world, but over the past months I’ve found very few books that, on an emotional level, genuinely affect me. Sure, a few have—I’ve reviewed them on Hellnotes, Horror World, or Horror Review. Also, I make every effort to ascertain I know as much as possible about the author(s) of any given book, and have a grasp of their intentions. If, for example, I know that Hugh B. Scriblin’s latest was written purely to entertain, I won’t come to it hoping for psychological realism and literary aesthetics—and will on those merits enjoy the story.

Nothing could have prepared me for Detritus in Love, and for that I’m grateful. “Now here’s an interesting collaboration,” pretty much summed my thoughts. This novella not only proved interesting, but managed to cure my apparent anhedonia like a plunge into icy water.

Teen-aged Det—full name Detritus, courtesy of his mother who “named him as a reminder of what he had done to her and the life she had been assembling for herself…a wonderfully promising career and future, a future that the unwanted pregnancy had hobbled,” early on receives what might be a prophetic message whose dead-pan delivery (considering the messenger) unsettles his already bleak existence. As that old superstition warns, it’s bad when in dreams the dead speak. Even worse when—to all appearances—we’re awake.

The authors create and sustain tension at once gruesome and poetic. Many times I experienced a rarified thrill of revulsion/attraction not encountered since first reading Peter Straub and Michael McDowell—cold, creeping horror just at the edge of perception. The most impressive moments in the story are inversions of common tropes: not necessarily threat/fear of death, but the soulless torment of being unbearably alive, yet unable to enter fully into life because you have no support system—even among those “close” to you. This is where we realize that Horror, when written with sensitivity, intelligence, and poetic vision can be as powerful and moving as anything in literature.

Fast-forward several years, and Det’s particular abilities allow him to see, and communicate with, those far more lost than himself: Terry/aka Schultz, whose final attire is a Nazi uniform, his lonely end abetted by bullies. Blank, who says “I’m not dead,” with a “voice [like] a hairline crack in a china plate…” A girl whose desperate fragility and rebellion are heartbreakingly common to the abused and forlorn used like servants and toys: She coasted on her looks and realized too late that the brakes were bad.

Det falls in love with her, which seems inevitable; a dark animus mirroring his damaged psyche. If his vacantly hostile mother’s account of Det’s birth (“The nurses said you cast a shadow in the womb. It showed up on the ultrasound. Like twins.”) explains the manifestation of The Opposite—a walking black hole whose corrosive presence marks the very landscape, then the original prophecy might carry catastrophic gravity.

Throughout, timeless images and truths we’d rather not admit haunt the narrative: “Black birds circled above like dirty water down a drain.” “A promise is a longer lie.” But maybe the most telling, and quietly devastating because so emblematic of what life can become, sorrows forth from Schultz: “Tired is being dead. And not doing anything about it. I’ve been awake for days and days and weeks and years…But I can’t rest. I’m dead.”