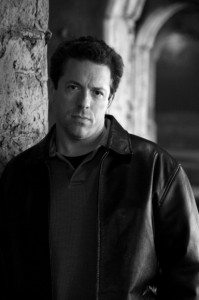

Welcome back to Deep Cuts! After a wonderful Women in Horror Month with my personal idols V.H. Leslie and Emily Carroll, today we welcome Richard Thomas. Richard is an old friend of Hellnotes and wears many hats: editor-in-chief of Dark House Press, a Litreactor writing instructor, and, of course, prolific author of horror and other shades of neo-noir.

Today we’re looking at Richard’s story “Asking for Forgiveness.” This one varies from previous selections because here, I think, the medium is the message. Pay close attention to the way that the language works, the way the narrator’s inner diction marries with his (gradually revealed) circumstances. This is the spoken word of a broken mouth, the swirling discourse of something between human and . . . other. Also, pay close attention to the gaps in the narrative – what’s there, what’s missing, and what’s beyond the knowledge of the narrator. We’re operating with a limited narration and, as you’ll see in the questions, I took this to be a process of whittling away but instead it was a process of building up. In particular, I find it fascinating that what I took to be the organic process of decay was instead the organic process of growth. See for yourself how you think it reads.

This is your last chance to read “Asking for Forgiveness” because **SPOILERS FOLLOW**

Hellnotes: While the first-person and present tense narration of this story gives it a very immediate push, the overall feel – to me – is something more fable-like or almost a parable. Part of this is the achronic setting: a single homestead surrounded by wilderness that could equally be post-apocalyptic and mutation-ridden or feudal and demon-haunted. The other part of that feeling, however, is that the dramatis personae are familial and intimate, which, ironically, hints at something broader than merely the labels of “mother” and “father” could convey. What, then, was the genesis of this story?

Richard Thomas: I think you really have some astute observations here. I wanted this to tap into fables and myths as well as that strange homestead feel, somewhere between Stephen King’s The Dark Tower and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. I also owe a bit of debt to both Stephen Graham Jones for his genre-bending work and Matt Bell’s In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods. Originally I wrote a very short micro-fiction story that was only 100 words. I really liked what I was doing in that but wanted to see more of the story. The idea of what a mother might look like in a world that’s falling apart, how she might want to keep her family going, even if things didn’t go right, if the children came out deformed, or even worse—due to radiation or virus or something else entirely—born normal and then slowly turning into something else. I like to write horror, but rarely do I write any of the traditional characters—vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons, etc. I wanted to describe these creatures and let the audience decide what they were. I’ve always been fascinated by worlds that are set after technology has faded, a regression of place and mind, where there are remnants of how far we went, but then, a more simple life arising out of the ashes, where the old gods might exist again.

HL: Another part of what I feel gives this story its distinctive and decidedly non-contemporary tone (in either direction) is the way that it feels like certain parts of the story have been dropped away through re-telling after re-telling. Even though we have a first person narrator and these lush descriptions, it could just as well be an oral tradition passed from generation to generation, during which the story’s cartilage has disintegrated, leaving these ornate, but merely suggestive, bones. How much more of the story was there in the initial drafts? What was the lodestar in your editing process?

RT: I think that’s the myth and fable seeping through. Whether it’s Hansel and Gretel or Little Red Riding Hood or The Odyssey, aren’t some themes eternal? Mother is such an important role, creator of life, the one safe place you can go, a garden, a softness, and yet that fierce determination, the home, the heart. Whereas father is seen as the muscle, the one to scare away the darkness, but also a source of violence, the one to lift and pull and kill, while still reassuring there will be a new day for lessons, for growing, for heroics. There was never more, in this story, originally. If anything there was less, I just kept expanding—slowing down, purposefully adding in sing song lyrical passages to tell that story—of magic, and wonder, and possibility. You can hear Paul Bunyan in here, as well as other tall tales, right? If anything was a guiding light it was the voice and my desire to make sure that anything was possible, that idea of magic, of danger, in this strange new world—and a new trend in my writing where I’m trying to put love at the center, instead of death. Although, of course, we have both here, right?

HL: One of the things that you and I have discussed in the past is the importance of finding and fostering one’s own “voice.” Here, that element is particularly pronounced – the long sentences, the loping gait of the prose that shifts and distorts, the alternately languid and vicious sentences (some lasting full paragraphs, some merely two words). What stylistic influences of yours do you see in this story? What parts of it (do you think) are “Richard Thomas” himself?

RT: Thanks for noticing all of that. I think I’ve always had an appreciation for poetry, and lyrical authors, as well as those voices that are simple and clean. Can’t get more different than the aforementioned King and McCarthy, right? But I grew up reading everything—all of those fables, myths and tall tales, as well as popular authors like King and Grisham, later getting to more difficult and unique voices like Kerouac, Burroughs, Palahniuk, and others. I listen to my words, the beats, especially with micro-fiction, which is where this began. I read the sentences in my head, and then out loud. If the beats aren’t right, I change the word. How many ways can you say cold—a lot, right? How many ways are there to say red or beautiful or lost? Besides the voices already mentioned of course, Will Christopher Baer and Craig Clevenger influence me, Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, Brian Evenson, Benjamin Percy, Lindsay Hunter, Amelia Gray, Roxane Gay, Craig Davidson, Jack Ketchum, Laird Barron, Mary Gaitskill, Flannery O’Connor, Denis Johnson, Haruku Murakami—it’s such a weird mix of voices. I think my own voice is a mix of those influences, a desire to write fiction that works on three levels—entertaining, moving forward in ways that are tense, exciting, and interesting; lyrical in a dense, poetic way tapping into the surreal, the sensory elements, finding ways to put the reader IN the moment, not at a great distance; and third, to create impact through my choices, by revealing characters that matter to the reader, in 100 words or 60,000 words, so that the audience feels something—laughing, crying, flushing, sweating, cringing. No matter how much I’ve read by the authors I’ve mentioned, I can only write from my perspective, which usually leans toward the tragic, but hopefully with some heartfelt moments along the way.

HL: Going along with that, you’ve also read this story out loud at This Is Horror (giving you the distinction of being our first audio story, too!) For all the intended artifice of the written word, prose is not speech, nor is it meant to be. For example, regarding dialogue, DBC Pierre has said: “The first law then: natural speech looks unnatural when written.” Did you intend for this story to be read aloud? To what extent is the oral presentation a significant part of your process in this, or any other, story? When you were writing this, how did you balance those elements?

RT: Well, I do read my stories in my head, and out loud. I like to make sure I don’t trip over anything, that the beats make sense. I want the pace and setting and tension to all contribute, to build a world, and tell a story that can be followed, all the while keeping your attention—hopefully keeping you on the edge of your seat, with an ending that hits you like a ton of bricks (or perhaps knocking you over with a feather), either way, leaving you spent. I read out a lot, and it’s important to select a story that isn’t too hard to follow, too long, one that can sustain the moment. If I’m doing my job right in writing, and reading, the audience will fall under my spell and the world will slip away.

HL: Finally, as a very prolific writer – particularly of short fiction – where can readers find more of your work in a similar vein? What about something completely different?

RT: More like this, I’d say “Flowers for Jessica” up at Mayday Magazine. For something different, try “Chasing Ghosts” in Cemetery Dance #72 or “White Picket Fences” in Shadows Over Main Street.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks