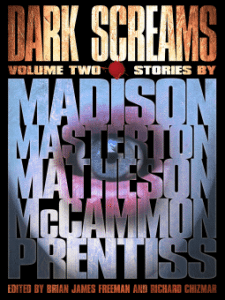

Stories by Robert R. McCammon, Norman Prentiss, Shawntelle Madison, Graham Masterton, and Richard Christian Matheson

Edited by Brian James Freeman and Richard Chizmar

Hydra (an imprint of Random House)

March 3, 2015

Reviewed by William Grabowski

Hydra’s second volume in their Dark Screams series is an exemplary follow-up, again presenting five works by masterful storytellers.

Three of the five are original to this anthology, and the reprints (McCammon’s “The Deep End,” first published in Night Visions IV [1987]; Matheson’s 1997 “Whatever”) are obscure enough to ensure that most readers will be coming to them fresh. I twice interviewed Robert R. McCammon for The Horror Show magazine, and was very pleased when he returned from a long hiatus.

“The Deep End” combines his strengths in characterization, vivid—often poetic, but never purple—descriptions, and frightening imaginative power. Glenn Calder and wife Linda mourn the loss, ruled accidental, of their 16-year-old son, Neil. Glenn, unconvinced the death was an accident, stakes out the location. Others have died here too, and Glenn imagines his son’s voice guiding him to some grim truth—or has grief and guilt simply driven him out of his mind? McCammon portrays with emotional and psychological realism the claustrophobic affect and singular anguish of grief, and (like Ramsey Campbell) blurs thresholds between individual fantasies and physicality. A grim, startling story.

From grim to grimmer, Norman Prentiss’ “Interval” explores our deepest suspicions and fears about air safety; the particular loneliness and isolation (yet privacy-violating) of airports. Flight 1137 has broken radio contact, gone missing…or something. Those waiting to pick up family, relatives, friends, etc., must rely on airline authorities either to assuage anxieties or—much, much worse—confirm them. The group waiting, gathered into a special room with refreshments and an updating wall-screen, do their best not to make eye-contact, fearing this might somehow realize what they’re all thinking. It’s impossible to say more without spoiling this chilling piece, but Prentiss’ prose will get under your skin, and put you in that terrible “Interval” between dread and destiny.

Shawntelle Madison is new to me, and I hope you’ll enjoy her “If These Walls Could Talk” as much as I did. Madison’s narrative unfolds with calm, reasonable precision, where set-designer Eleanor, assistant Gail and team, have driven from NYC to an expansive Victorian in southern Maine to prepare interiors for a film-production crew. Not one to compare authors, in this case I think pointing out echoes of Shirley Jackson and Gillian Flynn (two not dissimilar writers) will hurt no one. Checked in with home-owner Patrick, Ellie and Gail find more repairs and coverups (pun there) than expected, and get down to serious work. A horrifying discovery confirms rumors of the house’s past, unseating Ellie’s devastating childhood memories of abuse. Amid chill rain, plaster work, and other tasks, one of the crew vanishes. Affairs do not improve, no matter Ellie’s glib denial. After what she’s survived, very little is capable of drilling into her psyche. Except, perhaps, people who might have suffered even more than her. Madison displays wide knowledge of genre, and renders all too vividly the churn of memory and emotion haunting our lives. She is definitely on my favorites list.

Horror legend Graham Masterton’s “The Night Hider” is a more traditional—but no less creepy—tale mingling pulp convention with psychological horror. If King’s Night Shift collection had been an anthology, “The Night Hider” would have been a seamless fit. Young Dawn, overworked from a restaurant job, is jarred awake by menacing sounds and—worse—a rancid odor of something burning. At first she writes these off to hypnagogic states, but later has a more solid encounter with a horrid form she fears is residing in her recently obtained antique wardrobe. Boyfriend Jerry is both empathetic and skeptical, and soon loses one of those qualities. Dawn tracks the wardrobe’s origin, and discovers its true influence. I’ve always admired Masterton’s skill at evoking visceral supernatural threat, as he did in Mirror (1988), The Djinn (1977) and many others.

Richard Christian Matheson, known for the haiku-like brevity of his fiction, ironically gives us the longest story here. “Whatever” provides fly-on-the-wall access to iconic rock band Whatever, their various side projects, solos, lovers, drugs of choice, and everything you’d expect to see from an internationally acclaimed band from roughly 1969 to 1980—replete with letters, album reviews, in-house sparring, overdoses, memos, and (really powerful) lyrics. Matheson’s fragmented time-line results in an accumulative effect, and future events throw back shadows into the present, lending insight into why so-and-so behaved in a certain way. A drummer himself, and veteran of many bands, Matheson spares nothing and no one, baring music business realities (cynical no-talents grabbing attention; genuine talent and vision crucified to the Money Machine) capable of twisting artists into doing practically anything to gain entrance and adulation…or escape.