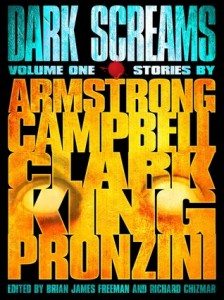

Edited by Brian James Freeman and Richard Chizmar

Hydra (an imprint of Random House) eBook

December 9, 2014

Reviewed by William Grabowski

This first in a projected series is a wicked treat, featuring five strong stories from some of the genre’s best.

The opening yarn, “Weeds” (1976), is a rare one from Stephen King, and the only reprint in the anthology. Many—if not most—of you have seen the movie version, “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill,” of this great pulpy tale in the King/George A. Romero collaboration Creepshow (1982), starring King himself as the regrettably curious (and under-earning) Verrill. While the Creepshow translation was—and is still—a genuine hoot, its early source takes itself a bit more seriously.

Sure, the humor is there, but Verrill’s mostly isolated existence and social unease lends him a poignant aura, so when the meteor falls and becomes a meteorite we see how quickly Verrill’s life changes. “Weeds,” beyond its pulp luridness, charges the reader with the anxiety and escalating horror of what it might feel like to discover one has some terminal disease. Whether this resonance was intentional, I don’t know—but it’s there. The odd-job man viscerally experiences the truth of that old saw “They grow like weeds,” especially when said weeds come from the unknown black beyond. Even knowing how this ends makes no difference, and is an early example of King’s rendering a bleak situation even bleaker.

Kelley Armstrong’s “The Price You Pay” explores the explosive power of secrecy, especially that between very close friends Ingrid and Kara. Kara’s history of bad choices has caused her serious problems, but now, moved across the country, she’s starting over with new husband Gavin. This doesn’t sit well with long-time thick-and-thin amiga Ingrid, and Armstrong does a superb job of rendering the often painfully subtle difference between narcissistic possessiveness and genuine protective instinct.

Gavin pulls an ugly trick, basically trapping Kara in a poison marriage. Her escape plan—like most of her other decisions—goes not how she expected…nor how you will. Nothing I’ve read by Kelley Armstrong hit me like this one, and those were good stories too.

Bill Pronzini, whose work I’m least familiar with, contributes “Magic Eyes,” wherein an accused wife-killer spins his yarn by way of journal entries suggested by his shrink as therapy (our protagonist is confined to an asylum). Edward James Tolliver may or may not be an unreliable narrator, and those keeping him locked up (keep in mind he’s “good with locks”) consider him psychotic. Tolliver laments his inability to convince his doctor he’s (Tolliver) sane, but after meeting—and perhaps falling for—Dorothy, who dispatched her parents with a meat cleaver, things seem to improve. But not really.

Pronzini gives Tolliver an average Joe believability, which makes the reader want to sympathize. Were it not for the magic eyes (about which I can say nothing without committing a spoiler), Tolliver might be just another depressed guy. Or not.

Simon Clark’s “Murder in Chains” immediately hooked me (pun there). My experience with Clark’s work is limited to Blood Crazy,a powerful, well-crafted novel, and a handful of shorter fiction—and this one ended somewhere both interesting and ominous, took the story nearly into a different genre. A man wakes to find himself in a vast underground chamber. Worse, he’s chained by the neck to another, let’s say, less-than-civilized fellow. Nearby rushes a channel of sewage, and when the other guy wakes our protagonist’s real fun begins. This other only grunts and growls, so we get no insight how he (or our viewpoint man) ended up in this reeking place.

A chance to escape comes up, but is thwarted by bad luck. The conflict in this piece is brutal and realistic, something Clark easily could have phoned in, but luckily for us his integrity won. “Murder in Chains” kept me going—I had to know where it was headed. And wasn’t disappointed when I found out.

Ramsey Campbell never fails—never—to remind me to keep a good 10 feet between myself and unidentifiable refuse in the street. In “The Watched” he combines perceptual ambiguity with the paranoia and tension provoked by a teenaged boy’s being trapped between (mostly) unseen criminal neighbors, the creepy, repellent detective surveilling them, and the boy’s well-meaning but nosy grandmother. As ever, Campbell’s clinical prose chills via suggestion and spectral dread (and often simply the threat of or potential for spectral dread). Over time, his skilled induction of existential nausea has only become more potent. Clearly, like the most honest writers, he’s following his obsessions. Even though I guessed the ending, I still enjoyed “basking” in Campbell’s grim atmosphere.

Dark Screams: Volume One is a strong start to what looks to be an outstanding series.