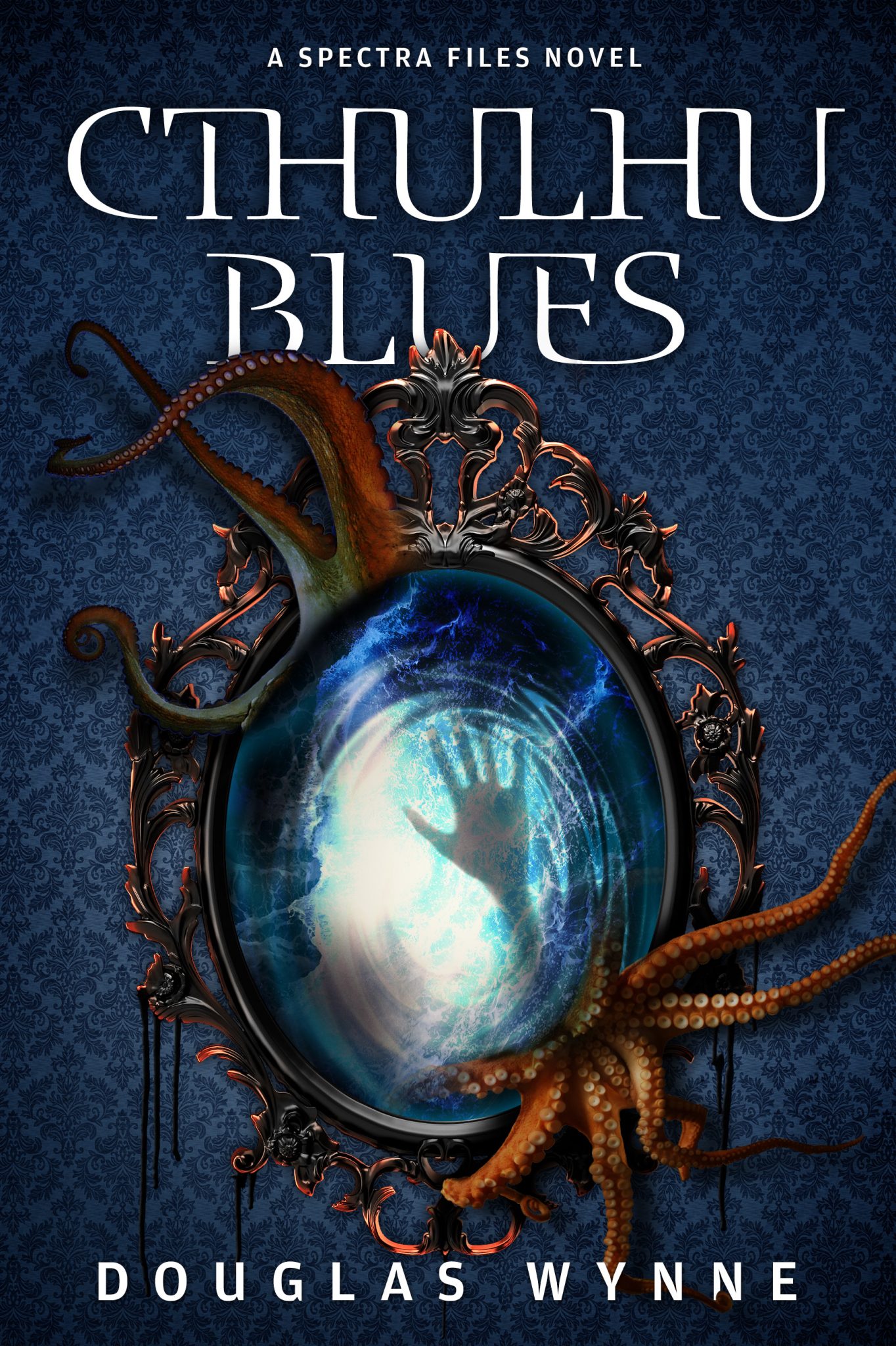

Cthulhu Blues

Douglas Wynne

JournalStone

2017

Reviewed by Michael R. Collings

In Cthulhu Blues, Douglas Wynne brings to a satisfying close the apocalyptic events begun in Red Equinox and continued in Black January, thus completing the SPECTRA Files trilogy. The series incorporates well-written thrillers, taut, exciting, and rapid-moving. It features secret agents, both loyal and traitorous; espionage and counter-espionage; threats to individuals and to all humanity; and weapons of mass-destruction unlike any the earth has ever seen before. It touches upon love and hate, selflessness and sacrifice, greed and the desperate hunger for power.

Much of it takes place in Boston, deftly incorporating elements of its history, geography, culture, and architecture into its story structure, giving the story a kind of gritty, almost noir realism.

And, oh yes, it includes a panoply of Great Old Ones…from Shabbat Cycloth, the Lady of a Thousand Hooks; to The Goat of a Thousand Young; to Yog Sothoth, Lord of Time and Space; to Nyarlethotep in a range of human and inhuman guises; and, in a remarkably restrained cameo appearance, to Great Cthulhu itself, dreaming unspeakable things in the hidden depths of the sea, in vast R’lyeh.

With almost invisible and highly commendable skill, Wynne merges these essentially antithetical genres into an escalating tale of impending destruction. What makes Cthulhu Blues particularly poignant is the heroine’s ultimate recognition that humanity’s destruction will come regardless of the choices she makes. Mankind is already wielding its own tools of destruction; that threatened by the imminence of the Old Ones will merely hasten the inevitable and paradoxically rescue all other life on earth.

This final chapter of the extended tale begins creepily rather than overtly horrifically: “On the night of the storm, Becca Philips sang in her sleep.” The fragmentary song becomes a chant in an unknown language…and the “unspeakable words” so often associated with things-Lovecraftian begin to be sung. With the help of Jason Brooks, a fellow-dreamer of inexpressible dreams, she begins a quest to discover and destroy the sole remaining transcription of Erik Zann’s Invisible Symphony, a musical key to opening a portal between this world and others. Their quest gains urgency and complexity when they realize that a handful of children are also developing the “voice” necessary for the chant and that those children, born immediately after the cataclysms detailed in Red Equinox, are being drawn by a mysterious Crimson Minstrel to the great Sea Organ on the coast of Croatia.

The Crimson Minstrel, on the other hand, has a single and simple goal: To sing the Symphony at the proper time and place, accompanied by the children’s choir, and waken Great Cthulhu.

What differentiates Cthulhu Blues—along with Red Equinox and Black January—from so many other Lovecraft-inspired tales is Wynne’s decision to incorporate historical attempts to harness the powers of gods and angels. Before the novel even begins, he quotes from Mozart:

The wonders of the music of the future will be of a higher & wider scale and will introduce many sounds that the human ear is now incapable of hearing. Among these new sounds will be the glorious music of angelic chorales. As men hear these they will cease to consider Angels as figments of their imagination. (Italics added.)

Then, throughout the novel, there are references to earlier—and often still influential—belief systems designed to penetrate to the eternal: the medieval construct of the Great Chain of Being; the Ptolemaic universe, with its crystalline spheres in which are embedded the sun, the stars, and the planets and whose harmonious movements create the Music of the Spheres; the Hermeticism that underpinned Renaissance Humanism and, paradoxically, modern science; the angel-speaking attempts of the Elizabethan magus Dr. John Dee, the preeminent mathematician of his day; secret societies such as the Golden Bough, dedicated to weakening the interfaces between our world and others.

Wynne wisely chooses not to bring these disparate threads to the fore, allowing them to provide context and texture as Philips, Brooks, and others—each for personal reasons—seek to achieve or permanently to make impossible the same magnitude of breakthrough…only this time, into the worlds of the Great Old Ones. Yet their presence adds resonance and depth to what in other hands might become merely an exercise in clichés.

While it is the capstone of a larger, more complex narrative, and deserves to be read as such, Chtulhu Blues does not depend upon readers being familiar with the previous novels. Wynne carefully words such references to provide sufficient insight for clarity. But readers coming upon Cthulhu Blues will almost certainly find themselves drawn back to the opening movements in the cosmic symphony that Wynne has composed. And they will be the better for it.

Wow! What a great cover on this book and a highly informative review!