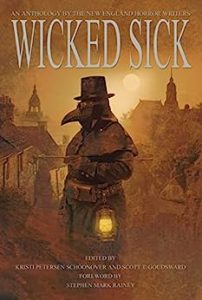

Kristi Petersen Schoonover and Scott Goudsward (eds.)

Wicked Creative (May 4, 2023)

Reviewed by Elaine Pascale

The New England Horror Writers (NEHW) hit another one out of the park (Fenway, of course) with Wicked Sick. It is a thought-provoking collection and I found myself ruminating over the ways it addressed the themes of mortality and fragility. Death is a common plot in Wicked Sick and there is an abundance of attention paid to cancer. This only makes sense as there are few people on earth who have not had cancer touch their families or themselves, and it was this realistic horror that interrupted my sleep more than any fictional boogeyman.

I have always admired the NEHW covers, and this was no exception. Mikio Murakami sets the tone with an eerie depiction of a steampunk plague doctor, who seems to be leading us toward a tragic darkness. I also regularly enjoy the poems, even though I fail to spotlight them in reviews. This collection contained poems that were distinct yet connected by their powerful imagery.

A few standouts:

“They Come at Night” by George Bastianelli was a somber way to begin. The dark figures that are mentioned in the story are scary but what resonated more was the fear that a parent has about leaving a child/children behind. A strange twist comes when you are a parent—you fear no longer being able to protect and help your children more than you fear your own death. Bastianelli was able to capture that fear with finesse.

Another parental fear story that felt a bit close to home was “The Cancer Ward at Midnight” by L. L. Soares. There is a saying, “a mother is only as happy as her saddest child,” and I repeat this often as it is one of life’s great truths. When a child is sick, or even worse, terminal, there is no happiness. As such, there is nothing to lose and nothing a parent wouldn’t do to end their child’s pain.

Catherine Grant elegantly flipped the script by taking the child’s perspective in “The Tall People.” The story is gloomy and atmospheric. As chilling as the Tall People are, I found myself wanting to see them (i.e., in a film or television show).

I was relieved for “Happy Valley” by Howard Odentz as it was a break from cancer and death, and a truly interesting one at that. The main character, Drake is a pyromaniac, and this inclusion of mental illness into the collection was a wise one.

Then, I read “Author’s Note” by Rob Smales and it broke me. I have long been a fan of Smales, usually because he produces a smile or laugh along with the chills, but this story made me hurt. As I said in the introduction, we have all been touched by terminal illnesses, especially cancer, and the experiences and emotions described were almost too on the nose for me. “Author’s Note” was wonderfully written while it stepped all over my most sensitive self.

There are stories in Wicked Sick that allude to the pandemic without being explicitly about the pandemic and that was another wise editing decision by Schoonover and Goudsward. The “House of Tupper” by Meg Smith was a unique take on vampirism and consumption. Smith provides the right amount of tension by letting the reader know early on that there are inhabitants in the attic and the basement but not revealing them until later. “The Cancer Eaters” by K. H. Vaughan also made mention of the pandemic and consumption and had a really cool second person narrative that reminded me of Bright Lights Big City mixed with Less than Zero.

I recommend Wicked Sick with the caveat that this is not a light, beach read. Be prepared for some uncomfortable moments. The stories are challenging and provocative and they do not allow for a reprieve from the reality that you, too, can become sick; that you, too, will one day die. That said, the authors are formidable writers, and the editors are skillful. That combination may help some readers to find catharsis or even closure by reading the stories.