S.L. Edwards

July 15, 2019 (Gehenna & Hinnom)

Reviewed by Bret McCormick

It’s been said that the sweet spot for horror fiction is between 1500 and 4000 words. Many of the most famous horror stories fall in line with this supposition. Far too many horror tales are unnecessarily lengthy, lessening any payoff these wordy tales deliver. Edwards understands the wisdom of keeping his stories no longer than they need be.

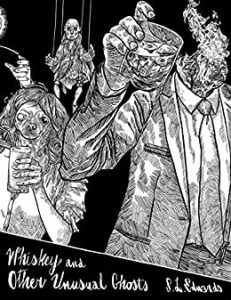

Though he sometimes uses tropes that are undoubtedly familiar to regular readers of horror, Edwards’ spin always offers a fresh perspective. One rarely has the sense of having ‘read this before’ as in works by other authors. The illustrations by Yves Tourigny on the cover and throughout the book add an additional layer of enjoyment to these darkly human and supernatural stories.

A few of the stories could have benefited from another pass of editorial scrutiny, but none of the flaws in style or grammar were severe enough to prevent the enjoyment of S.L. Edwards’ unusual flights of imagination. There’s a deeply human quality present in this work, a willingness to reveal emotion without venturing into maudlin territory. This willingness on the author’s part to reveal himself in such an unguarded fashion is rare, especially in horror fiction, the genre as a whole having accrued a great deal of cynical prose.

It is my habit to ‘collect’ phrases from the books I read, those bits that stick in my mind, holding particular meaning for me. The following line by S.L. Edwards lingers in my mind: “It is hard for me to find anything worth hating or loving in the vast majority of people…”

Artists of all kinds, including authors, tend to explore concepts repeatedly from slightly varied perspectives. Edwards’ explorations are readily apparent, perhaps because this is his first anthology and he may not have had a very large body of work to draw from. “Maggie Was a Monster” and “I’ve Been Here a Very Long Time” cover much the same ground, albeit entertainingly enough on both counts. “Cabras” and “Volver Al Monte” are also very similar in tone and subject matter, but demonstrate the degree of talent and skill Edwards has attained.

Maggie Was a Monster. Things that terrified us when we were children become mundane and sometimes even appealing after we’ve grown, especially if we are addicts. The monster endures solitude for years in Maggie’s closet, but when he finally gets out, he sees that Maggie has become a monster, too.

I’ve Been Here a Very Long Time. Turn Maggie into a boy named Carl, and you’ve got the same story as Maggie Was a Monster, from a slightly different perspective.

When the Trees Sing. Peer pressure makes people do ugly things. In times of war, that pressure’s greater and the results more horrifying. This is the story of a man who couldn’t stand against that pressure, couldn’t stop the deaths of his wife and daughter, couldn’t die and couldn’t live with himself.

And the Woman Loved Her Cats. It’s been said cats love no one, that cats are for people who want to display a modicum of affection for another living creature, but don’t really want the messiness of affection returned. Madame’s cat Behemoth is evil, supernatural, and willing to pit his wits against those of any human.

Golden Girl. Clowns, ventriloquist, dummies and puppets have always had a sinister subtext lying just beneath their humorous veneer. Edwards taps into this esoteric goldmine and provides a novel take on an enigmatic itinerant female puppeteer who steals more than just hearts.

Movie Magic. There are two kinds of horror fans: horror lovers and horror livers. Peter is pretty serious about horror literature and films, but he hasn’t crossed over the line from lover to liver … until he goes on a date with Camilla to the Haunted Palace, a retro cinema specializing in horror films.

We Will Take Half. Trolls, fairies, and changelings have long been said to steal human babies, leaving their own grotesque offspring in exchange. In this updated version of the fairy tale premise, Edwards shows us what happens when a simple man requests a changeling child and makes a strange bargain with the blue folk.

The Case of Yuri Zaystev. Though Yuri and his father were good Party members, shifts in the political winds blowing through Moscow determined that they would end up in Siberia. Yuri had it better than most. It was his job to deliver corpses to the unrelenting ice not far from the gulag. But even this relative privilege is to be taken from him when he stumbles onto a strange bloated and warm cadaver.

A Certain Shade. Obsessed with the color of his dead brother’s flesh, a struggling artist tries repeatedly to duplicate the grim hue, only to encounter failure. In his creative desperation, he arranges to acquire a fresh corpse with unholy consequences. This tale has an archaic quality. Were it not for the mention of email, one could easily imagine this story taking place in the early 20th or late 19th century.

Cabras. This story concerns warfare in South America, and the fate of a desperate and aging guerilla who escaped and hid in a mountain village to save his loved ones. One of the more mature works in this collection—mature in its artistic vision and mature in its literary skillfulness. In an era when most horror fiction has become artless, self-referential echoes of film and television, Edwards shows himself to be well-read in history and capable of bringing a worldly perspective to the genre.

Volver Al Monte. Another nicely polished example of Edwards skill with horror stories. Like “Cabras,” this one revolves around the subject of war in Latin America. Traditional wisdom would not place these stories adjacent to one another, or even in the same anthology. However, both have significant strengths and leave a powerful impression on the reader.

Whiskey and Memory. Edwards informs us that this story is the oldest in the anthology, begun when he was in high school, so it’s understandable that it is not equal in quality to the previous two. It’s a good descent-into-hell story, but necessarily will have a familiar feel to it, as there have been many similar tales written in our Judeo-Christian influenced society.

Prophecy in Brief. This final offering is a very short piece, basically a retelling of a dream Edwards had. It’s dark and memorable.

One walks away from Whiskey and Other Unusual Ghosts with the sense of having been given a sincere glimpse into one man’s psyche; the subject matter, the obvious evolution of the author’s craft and the personal notes attached to each story convey a deep desire to communicate and to do it honestly. In this day of ‘branding’ and individual authors foolishly trying to emulate strategies used by corporations with deep pockets, Edwards’ sincerity is a rare and welcome experience. May he enjoy a long and successful career in writing.