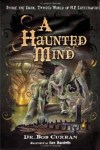

Dr. Bob Curran

Illustrasted by Ian Daniels

Career Press/New Page Books

$19.99 trade paperback

Review by Michael R. Collings

A Haunted Mind: Inside the Dark, Twisted World of H.P. Lovecraft is frustrating. From the subtitle on, it makes assumptions and assertions about Lovecraft and his worlds – both real and fictive – that are never fully discussed or documented. It eagerly delves into the intricacies of the “Cthulhu Mythos,” first as developed by Lovecraft himself, then as expanded by subsequent writers, then as codified and analyzed by Lovecraft scholars, and finally as connected, however peripherally or tangentially, to parallels in history, mythology, legend, and landscapes. Yet ultimately, it leaves one feeling as if there is as much fiction and imagination in the various treatments as there is in Lovecraft’s stories themselves.

SECTION ONE takes on the mystical tomes central to the mythos: the Necronomicon, De Vermis Mysteriis, the Book of Eibon, the Cultes des Goules, the Pnakotic Manuscripts, and others. Initially, each sub-section deals with the history and contents of the various books as developed by a panoply of Lovecraftian writers – interesting in itself, although the prose often comes close to assuming that the books actually existed; then Curran looks at historical documents that might have, could have, perhaps influenced Lovecraft.

SECTION TWO concentrates on the monsters: Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep, Yog Sothoth, and the rest. Again, each sub-section treats the monsters as they develop within the fiction of Lovecraftian writers; then looks at the histories of analogous monsters in myth and legend and tries to identify traits of the Yeti, Sasquatch, the Wendigo, and others that might have, could have, perhaps influenced Lovecraft.

SECTION THREE describes the various landscapes associated with Lovecraft’s stories: Dreamlands, Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, Leng, and others. As might now be expected, the sections begin by trying to make as precise as possible Lovecraft’s often vague descriptions of the various locales, then include later writers’ modifications, and finally look at the possibility that specific ‘real’ landscapes might have, could have, perhaps influenced Lovecraft.

Those three phrases recur throughout A Haunted Mind; they, and a slew of conditionals, subjunctives, modals, and other means of avoiding declarative statements, occur so often that, to paraphrase Mark Twain’s famous comment on another book, without them, A Haunted Mind would be little more than a pamphlet.

This attitude toward language and fact leads to several problems so severe that, for me at least, they overshadow Curran’s intentions and performance.

The introduction sets the stage for the rest of the book. It is a purported biography of “Howard,” an approach that suggests an intimacy with the subject that does not exist. Yet it does so without offering any evidence or support for what would otherwise be considered scurrilous allegations. For example, Curran writes: “Some have commented that, for Lovecraft, it was ‘love at first dollar’ (18) summarizing an unnecessarily long and negative assessment of Lovecraft’s marriage; yet nowhere is there any support for the statement – its authority rests on an unnamed “some.” Not the language of scholarship or accuracy.

Later in the same section, Curran notes offhandedly that Lovecraft, “Either too hopeless or too lazy to find work,” spent several months “sightseeing, meeting friends, or writing” (20), apparently unconcerned with the fact that writers write. Then a sentence or so later, he states, again without explanation, that at the time Lovecraft was earning a “meager salary.” So which was true – and if the first, where did the salary come from?

This kind of problem recurs throughout A Haunted Mind. Lovecraft’s actions and writings suggest necrophilia, but of course there is no evidence of it; so why bring it up? His relationship with a thirteen-year-old boy “led to the suspicion” that Lovecraft was a “sexual predator, obsessed with young men and boys” (22); yet in the next sentence, “there is absolutely nothing to suggest that this was the case.” Why then the discussion of something that never existed?

“Whether this is true or not,” “This is probably because,” “he may have taken beliefs,” “there is little doubt” “The real reason is probably” – all of these structures constitute ways of introducing into the biography and elsewhere elements that are simply assertions by the author, his private deductions presented as fact, or otherwise debatable issues that he apparently felt important to his portrayal of Lovecraft as having a “haunted mind.”

I could extend the examples, but there are more important, more substantive problems with the book.

The book is patronizing in its presentist attitudes toward complex and difficult issues that would require more than a few paragraphs to delineate clearly. After giving several examples about Lovecraft’s racist and bigotry, he concludes, rather with relief, I think:

Of course, such sentiments would not be tolerated today. Perhaps it was the

perception of himself and his family as the inheritors of the puree [sic] English stock

that engendered in Lovecraft a deep-rooted racism and bigotry. (12, my italics)

Curran – perhaps not coincidentally of Irish birth (oops! There I go making the same kinds of assumptions about him as he does about Lovecraft) – seems not to note the sneering tone, the ethnocentrism in his own conclusions. Or the error in spelling.

Throughout, Curran refers to Lovecraft scholars, to historians, to those who knew Lovecraft, yet never once does he provide a solid source; only a handful of times does he even offer a title. There are no footnotes. There is no bibliography. The index lists names of creatures, titles of books both mythical and real, but rarely actually directs readers to the text for discussions of substantive issues in Lovecraft’s biography or works. What little critical apparatus is present is nearly worthless; what is missing is any way for readers to follow assertions or allegations back to original sources.

In addition, the text reads like the script for a television special on ancient mysteries, the supernatural, and the inexplicable. Rather than concluding anything, sections end with leading rhetorical questions. In the discussion of the Necronomicon, for example, the final lines read:

The Necronomicon is, arguably, one of Lovecraft’s most famous creations and its

fearsome reputation has reverberated all through the Cthulhu Mythos. Does such a terrible

book truly exist? We can’t really say for sure, but if it does, perhaps the quest for it

is just as intriguing as the discovery of the tome itself. (51)

Never mind that the question contradicts the first statement: If Lovecraft created it, how can it exist? Or the diction: “fearsome,’ “terrible,” “quest,” “tome,” all horror-inducing words that have already been overused in the earlier text. What irritates is the tone, the speculative glee, that surfaces time and time again, never to be answered.

Finally – and for me in some ways the most damning – the book is simply poorly produced. Already on page seven there is an indication of what is to come: “Whipple Phillips also boasted an extensive library, and from these tomes the literary education that Howard received from Louise Imogen Guiney began to bear fruit, as he started to read voraciously as soon as he was.”

Was what? The sentence simply breaks off.

Page eight, speaking of a carriage house in which Lovecraft played as a child: “The children drifted away, but Lovecraft continued to lay alone in the now-abandoned Engine House.”

Lay?

If these were the only problems, they might be overlooked, but they are not. Sentences incorrectly coupled with “, however,” lead readers to wonder which half the however refers to. Phrases repeat unnecessarily from one sentence to the next and even within the same sentence. Words are misspelled: “puree” instead of “pure.” Letters are simply deleted: “s” instead of “is.” Italics and capitalization are used at random; part of the time Cthulhu is granted god-like status as “It” and part of the time is merely “it.” Misplaced punctuation: “But, Sonia was strong-willed…” Ill-defined pronouns: “That same year, Robert Howard committed suicide, which had a great effect on him.” I suppose it would, assuming from the syntax that him refers to Howard.

And on. And on. All within the confines of the introduction. Nor do such problems lessen in the text itself.

I enjoy reading about Lovecraft. He was an odd individual, whose personal traits often reflect in his fiction. He was reclusive, intellectual, past-looking in many ways (I appreciate the 18th-century convolutions in his prose), yet open to his many correspondents. He wrote voluminously – fiction and long letters that offer readers legitimate insights into his works and his mind.

Curran’s book, however, reminds me of a series of books published some years ago about Stephen King’s works. After three volumes of essays and interviews, initially published in exclusive hardcover for enormous sums, the editor admitted in a postscript to the final volume that, personally, he considered King a hack, not worth the time or the effort to read, let alone to read about. But, he concluded, everyone else was making money off the King cottage-industry; why shouldn’t he?

I’m not sure why A Haunted Mind was written, other than to take advantage of the current interest in Lovecraft; or precisely who the intended audience might be. I wanted to enjoy it and take new information away with me.

Sadly, I could not.

But on a final positive note … Ian Daniel’s full-color cover and black-and-white illustrations for the various chapters succeed remarkably well in capturing the tone, the atmosphere, the eldritch quality of Lovecraft’s prose. Again and again, I found myself looking forward to turning a page and finding yet another artistic gem.

Many thanks for this thoughtful and intelligent review. The book’s author has posted a new blog in response to my Amazon review, in which I couldn’t contain my anger, so it’s probably not very useful AS a review of the book, being more a showcase of anger. I’ve “liked” your review on Facebook and hope that this may bring it to the attention of many others. I cannot understand why the gent wrote the book, since in his new blog he confesses that he does not like Lovecraft as a person or admire him as an author. So why, then, write a book about him? Inexplicable. (He also misspells “weird,” which is a cardinal sin among we who write weird fiction–ha ha!)

I suspect the “puree” of “puree English stock” is not an error, as the English are otherwise lumpy if you try to cook with them. 😉

Phillip