Interview conducted by M.G. Allen

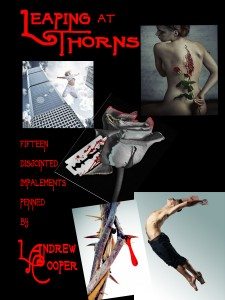

L. Andrew Cooper is the author of the recent collection Leaping at Thorns (Blackwyrm 2015) (reviewed here), as well as two previous novels. In addition to the discussion below, we have a longer discussion with him available at companion interview at Horrorworld.

Hellnotes: How much planning goes into your writing? Do you painstakingly outline or do you just let ‘er rip?

L. Andrew Cooper: For my first three, unpublished novels (only one of which is any good)—I covered sheets and sheets with outlines, but now I keep most of the outlining in my head so I can improvise and let characters lead me, which makes early drafts more intense. Before I was an academic (next question) I was just a plain nerd, obsessed with patterns and structures. Nerd example: my novels have numbers that determine their structure and recur in patterns. Burning the Middle Ground is a 3, and Descending Lines is a 2 (my first two novels were 5s, but no daylight for them, and my third novel is a 3, but it scares me). Descending Lines is about a husband and wife whose relationship is falling apart while they come closer and closer to the possibility of sacrificing the baby the woman is carrying so a supernatural ritual will cure their six-year-old’s cancer. It goes back and forth between 2 perspectives, is in 2 major sections, pairs characters to highlight relationships, etc. In Burning the Middle Ground, each of the 3 main sections has 27 (3^3) short chapters, and most of the story takes place during Easter…. If people notice this stuff, cool, but I think it makes a difference regardless: especially since I write so much about paranoia, patterns in the writing (like women in the wallpaper) can erode your sanity without you noticing.

HL: You have such an academic perspective on horror. What’s your philosophy of the genre?

LAC: I hope the fiction doesn’t read as academic—being a horror fan made me a horror scholar (it was the focus of my PhD and is the specialization of my research). I was writing horror stories in the third grade, when I still planned to be a police detective, so I have a constant fear that the required manure in scholarly prose will stain my creative writing! Yet my honest answer to a philosophy question, while personal, will sound pretty darned academic. Let’s say intellectual—“academic” deserves a stigma, but “intellectual” does not. Anyway, horror for me is an aesthetic sensibility (a way of seeing things in particular artistic terms), but it is also a state of mind. I have recently come to understand much better the degree to which the genre structures not just my view of the world but the very shape of my thinking.

all violent possibilities in real life, I turn that around in fiction, and lately I’ve been churning out my most bizarre, gory fiction ever… and my reading circle is excited. In the past, short stories would incubate in my mind for months, but these have been popping up and popping out days later. Some of them I’ve already offered to anthologies, and I’m already thinking about another collection, which I’m tentatively calling Peritoneum, because patterns connect them in many, many ways (they’re almost interconnected enough to be a Winesburg, Ohio with a five- or six-digit body count). The bottom line is that my brain has been processing all-too-common work stress into grandiose horror. So horror, at least for me, has become a way of seeing, thinking, and even being—which in philosophical terms means it combines aspects of the epistemological with both the phenomenological and the ontological. Boo-yah.

HL: What do you consider good horror archetypes?

You see, when you use a word like “archetype” you tap into the academic again, so here goes. No archetype is good or bad; the quality depends on how and when it’s used. Take, for instance, the Gothic archetype of the woman in peril in the old castle or house. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, this figure was as common as pretty girls being chased by men with sharp things are nowadays in the movies. It works so well in Anne Brontë’s 1848 novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, about a woman trapped by an increasingly sadistic husband in a society that gives men overwhelming power, that I still consider it one of the scariest books I’ve ever read. Today, though, resurrecting that exact archetype in that exact form would be rather difficult to do in a relevant way. And I think we’ve over-mined the vampire and zombie of late, so we need to look elsewhere. I am pleased by the turn to what Lovecraft called cosmic horror—horror based on this world or worlds in general that confront us with frameworks in which the human is insignificant—but the archetypes at our disposal are at least as diverse as a Monstrous Compendium, and one can always mix and match to create a new cockatrice. Pick up Brian Keene’s Earthworm Gods (a.k.a. The Conqueror Worms). Yeah, he wrote a good zombie book, but he wrote an even better series of worm books.

HL: Leaping at Thorns is broken up into three segments: complicity, entrapment, and conspiracy. Explain what this means and how they are utilized in this work.

LAC: I like to point out I have a story called “Complicity” in the Conspiracy section rather than the Complicity section. The sections (or panels of the triptych) are named after themes (or obsessions), which are inseparable from each other: people become complicit, even entrapped, in conspiracies, and so on. However, the panels are also distinct in that each set of five stories focuses more on the panel’s theme (3 and 5… numbers again). “Charlie Mirren and His Mother” explores an almost unthinkable form of complicity, and Margaret in “Bees and Bears” becomes complicit in her mother’s murderous relationship with bees… but she reaches a limit. Similarly, the Entrapment section begins with “Hands,” which devotes much of a narrative to a child literally trapped in a mud pit rapidly filling with water. The “Conspiracy” section has the added distinction of consisting entirely of stories set in the universe surrounding Dr. Allen Fincher, whose legacy, especially through his book The Alchemy of Will, lies behind both of my published novels as well as stories published elsewhere already and forthcoming.

HL: Explain the title Leaping at Thorns? How does the title fit into the overriding theme of this collection?

It’s about masochism, and it’s related to the epigraph from Charles Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil. The step beyond the rose and the thorn, the source of pleasure and the source of pain, is to sacrifice yourself on the source pain in order to get closer to the source of pleasure. It’s not about inflicting the pain, though, which is why I think it’s really all about masochism. In a way, many of my characters are masochists, or blinded to their circumstances by a drive toward self-destruction. But also, I think reading a few of these stories is a pretty masochistic act. Writing them was.

For more with L. Andrew Cooper, check out the companion interview at Horrorworld.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks