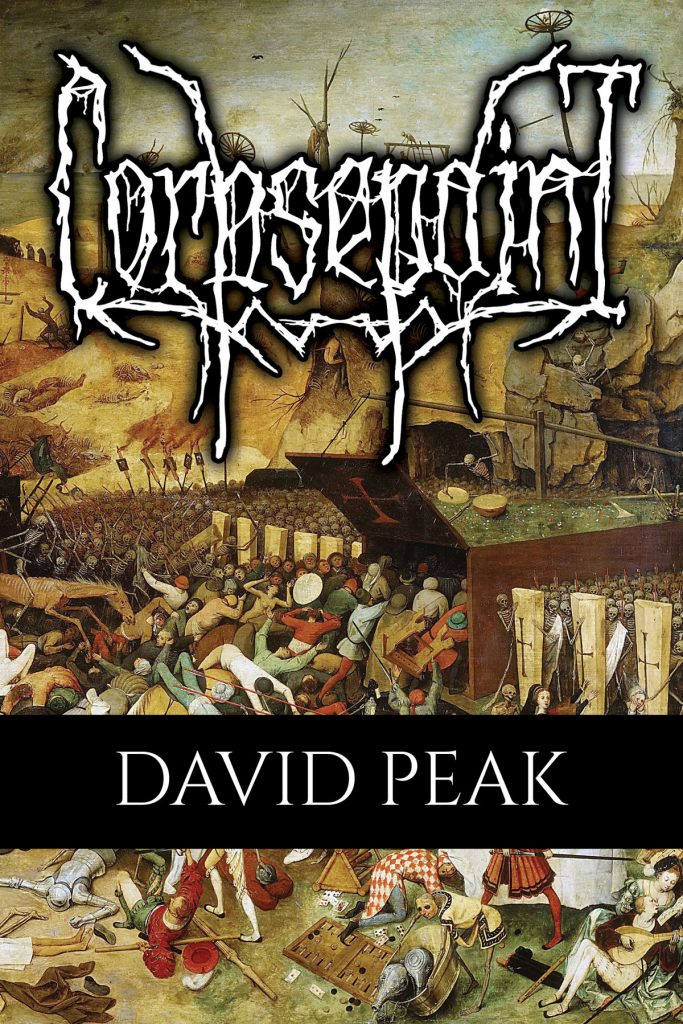

Today we’re talking to author David Peak, who’s new novel Corpsepaint is now available from Word Horde. We discuss his novel, black metal, and the strange path of coming to fiction via existential nonfiction.

HELLNOTES: Let’s start with the equivalent of the pre-show mix-tape: For our readers who don’t know, what is Corpsepaint about?

David Peak: Corpsepaint is a cosmic-horror novel about two American black metal musicians who travel to Ukraine to record an album with the mysterious cult act Wisdom of Silenus. Obviously, things get pretty weird after that.

HN: On that same prefatory note, do have a particular line or passage that you can give us that you think either captures its tone or will otherwise whet the appetites and/or blow the minds of our readers, so much so they can’t help but click here to buy it?

DP: From the first page of the book:

Roland woke beneath a heavy weight, a shadow in the dark room. He opened his eyes and saw a black motorcycle boot planted mere inches from his skull.

The image that took form in his mind, rising up out of the mucky swirl of sleep, was that old painting, Fuseli’s Nightmare, or some version of it, the one with the woman in the white dress lying on her back, that furry devil-thing sitting on her chest. The look on that devil-thing’s face, it looked like—

“Max?” Roland said, or tried to say, his voice scraping up and out his throat. Still half asleep, disoriented, it took him a few seconds to realize that Max had one hand around his neck, thumb and first finger clamped down.

This is real, Roland thought, strangely calm, resigned to whatever it was that was happening. Here he was, getting murdered.

HN: Now that that’s out of the way, what can you tell us about the genesis of Corpsepaint? It certainly seems like you’ve been considering the ties between black metal and cosmic horror for a while, but while you’ve written some dark fiction and book length non-fiction about our “horror reality” before, what sparked your interest in doing a novel and why this one?

DP: I’d always had the idea for a novel like this one somewhere in the back of my mind, something inspired by the imagery and concerns of black metal. One of my early outlines was about a group of musicians who travel to Romania to climb the Carpathian Mountains. There was going to be some sort of unexplained shift that would throw them into medieval Transylvania, back in the days of weirdo castellans and creepy monsters from folklore. It wasn’t a great idea, and rightfully never made its way to the page. But some variation of that idea just wouldn’t leave my imagination. Over time the story that needed to be told revealed itself, and then it became its own thing, and then one day I sat down and started writing it.

HN: One of the things that I appreciated about the novel was that although it draws from black metal, knowledge of that music scene is in no way a shibboleth for enjoying or understanding the book. That said, for our readers who may not be as well versed, could you explain what “corpsepaint” is and maybe a little of how it relates to the novel? There’s a specific real-world term in black metal, but it also seems to take another meaning over the course of the novel as the themes of the cosmic void are elaborated on.

DP: Corpsepaint is a style of makeup or face painting with the express goal of making someone look inhuman. Depending on how it’s done, it can either look really silly or really scary. On the sillier side there are people like Abbath, and on the scarier side there’s Nattefrost and the dudes in Abruptum and Watain. Either way it’s still pretty silly, but that’s why I love it—it’s theatrical.

My editor and publisher, Ross Lockhart, actually came up with the title for the book, and I thought it was fitting. It captures the spirit of the thing. This is a book about people who are intent on “living out” the message of their music, even if that means sacrificing themselves, or killing anyone who gets in their way. It not painting your face, it’s about embodying a system of beliefs.

HN: Black metal is a particularly interesting choice of music to incorporate into the book. Beyond just its capacity for political undertones – which is something that a lot of music shares – black metal is one of the only genres that springs to mind as also having explicit philosophical undertones. More than just lyrics, it is often the sonic landscape that invokes the kind of existential pessimism that Corpsepaint confronts and, perhaps, literalizes. I wonder if you could talk briefly about how you view black metal, cosmic pessimism, and in particular how you drew them together for Corpsepaint?

DP: For me, black metal has always been about two things: misanthropy and Romanticism. It’s no coincidence that both of those things are extreme forms of individualism. Beyond that, I’m loath to talk about what black metal is, or what it means, because many people have their own ideas, and mine aren’t anything original.

Cosmic pessimism, at least as I understand it, is philosophy that’s rooted in the Lovecraftian notion that man should never know his place in the universe. Before our consciousness there was nothing, and after our consciousness there will be nothing again. Communing with that nothingness, with an underlying reality beyond our comprehension, or with the sheer vastness of a world-without-us, all of that fascinates me to no end.

At the heart of both of these ideas remains the human, alone and against the world. That’s where black metal and cosmic pessimism connect. Black metal, or music that rejects so many of the things that make music attractive to so many people, winds up becoming this expression an antihuman, antilife mindset. The idea of that appealing to people, utter hatred and virulence, of that becoming a means of spreading destructive beliefs—that’s what this book is about.

HN: Corpsepaint draws a lot on physical spaces – from the grunge of Strigoi’s Chicago, to Prague and its Astronomical Clock, to the bleak landscape of Ukraine in winter. It also draws on visual art, black metal music, and, it seems, even some local folklore for some of the supernatural elements, although that may just be your own rich imagination. What kind of research did you do for this novel? Were there explicit resources that you drew on, be they fictional, factual, or philosophical? What about merely tonal ones?

DP: I actually did more research on goats giving birth than anything else, which was an interesting way to spend a few weeks. But beyond that, I live in Chicago and I’ve spent some time in Prague, so those things were already there, they were already developed in my mind. The latter half of the book is set in Ukraine, and there are a few reasons for this: first, it’s a nod to one of my favorite bands; and second, this story had to take place in a part of the world that once had medieval voivodes, or rulers who were essentially warlords. The real horror in Corpsepaint, the thing that haunts the present is connected to the land, old tales of murderous and barbaric tyrants, of blood spilled, and so all of that had to tie together and make sense.

Obviously the name of the band Wisdom of Silenus has thematic importance, and so do many of the paintings referenced throughout—Bruegel and Friedrich, mainly—and all of that is reflected by the attitude and posturing of black metal. I guess I had all of this stuff in the back of my mind as I was putting the book together, but mostly just because it’s the kind of stuff I like to think about.

HN: I mentioned above that you’ve written a book length work of non-fiction, The Spectacle of the Void. I’m curious as to what differences you found in developing an argument through non-fiction versus fiction? Why did you decide that Corpsepaint was best explored through a novel, rather than a non-fiction book or essay?

DP: Well, I’ve always been a fiction writer. My background is primarily writing fiction. The Spectacle of the Void was sort of a deviation from my other books. I honestly never thought that book would sell even five copies, so it’s surreal to think that many of my readers are discovering my fiction through my nonfiction.

I didn’t want to actually say anything explicit with Corpsepaint—I didn’t want there to be an argument. When I sat down to write The Spectacle of the Void, I knew what the argument was because I’d been developing it in my mind and my essays for a number of years. But with Corpsepaint I wanted to work with a self-contained structure, just focus on the vision of it and see where that took me. If there’s any art to it, it’s incidental.

HN: Where do you see your influences – not just for this book, but in general? Who are some of your literary and philosophical forebears? Beyond that, however, who (or what) are your influences/preoccupations/etc. from the larger world?

DP: I tend to appreciate writers who saw the world in a unique way, who worked on literature that was as personal as it was universal. That really inspires me. I like people like Kafka and Kavan, Schulz and Ligotti. I adore Shirley Jackson.

When I was writing Corpsepaint, though, I was primarily inspired by the early novels of John Hawkes, whose nightmarish and fractured prose helped usher in the postmodern era. Hawkes believed that totality of vision was the heart of fiction. He believed that plot, character, setting, and theme were the “enemies” of fiction, which is funny because if you read some of those novels—The Cannibal, The Lime Twig, The Blood Oranges—you’ll see that they’re crammed with plots, characters, settings, and themes—it’s just that those things aren’t the focus of the narrative. They’re buried beneath something more interesting, a smear of moods and shadows.

HN: Before we wrap up, could you give us just a brief sample of an appropriate playlist for background music as readers delve into Corpsepaint? If you’re feeling up to it, too, how about a palette cleanser for afterwards?

DP: I’ll try to keep this brief and just list the specific songs that helped inspire and that also tell the story of the book. This isn’t meant to be anything definitive; these are just some of my favorites, with some classics thrown in for good measure:

“A Fine Day to Die” – Bathory

“In the Shadow of the Horns” – Darkthrone

“Braablick Blev Hun Vaer” – Ulver

“Furrows of Gods” – Drudkh

“The Blacksmith and the Troll of Lundamyri” – Windir

“The Swordsman” – Carpathian Forest

“Vexed and Vomit Hexed” – Leviathan

“The Loss & Curse of Reverance” – Emperor

“Soulreaper” – Dissection

“…The Meditant (Dialogue With The Stars)” – Blut Aus Nord

HN: Finally, what’s next on your horizon? In addition to your fiction, are you working on any further nonfiction? Beyond concrete projects, are there any particular ideas that you’re interested in exploring next?

DP: I’m in the process of outlining another novel, but I’m taking my time. It’s much more ambitious than my previous books. This one is about the woods and witches and mythmaking and LSD and feuding families. I’m pretty psyched about it. It’s got kind of a doom metal vibe, which is more where I’m gravitating these days. So we’ll see what all of that looks like when it comes together.

David Peak is the author of Eyes in the Dust (Dunhams Manor, 2016), The Spectacle of the Void (Schism, 2014), and The River Through the Trees (Blood Bound Books, 2013). His writing has been published in Denver Quarterly, the Collagist, Electric Literature, 3:AM, and Black Sun Lit, among others. He lives in Chicago.

Order Corpsepaint here: http://wordhorde.com/books/corpsepaint/

Website: http://davidpeak.blogspot.com

Facebook: Never

Twitter: Fuck no

Trackbacks/Pingbacks