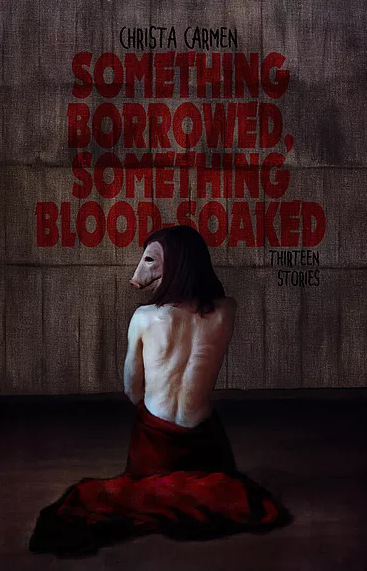

Hellnotes: Congratulations on your debut collection Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked! For our readers who aren’t yet familiar with you and/or your work, could you tell us a little bit about yourself, what kind of horror you write, and maybe how you started writing?

Christa Carmen: Thank you! Now let’s see, what can I tell you about myself that isn’t already on my website or in the media kit for my collection? I am thirty-three years old, and in a month and a half, on October 13, 2018, will celebrate my five year soberversary. I did gymnastics for fifteen years, from age seven or so until my senior year of college at the University of Pennsylvania, and am confident that my involvement with that sport contributed greatly to my often stubborn and occasionally intense disposition.

I love animals and have a slight obsession with seeing them in the wild. I have half a dozen bird feeders scattered around the yard, and if I come upon a herd of deer or a flock of turkeys while walking my dog, I have to remain rooted in place, observing them until they move on, or until Maya has exhausted all of the available smells in the vicinity with her super-powered beagle nose.

I’m a tea freak, and have an alarm clock teapot that wakes me up each morning (English Breakfast only please, none of that disgusting Earl Grey nonsense). I love Halloween of course, and leave a few decorations up that are particularly close to my heart year-round. I have one entire closet dedicated to black garments, and harbor a gorgeous, gluttonous fantasy of planting a sprawling English perennial garden of black and other dark-colored flora. On a side note, I always spell the word ‘perennial’ wrong on the first go-around.

I write all types of horror, from comedic to Gothic and everything in between. I stay slightly removed from writing the traditional horror villain stories—vampires, werewolves, etc.—although I’ve certainly penned stories that contain monsters. I’ve always loved writing, but committed myself to it more seriously after getting back into recovery five years ago. I recently found a story I wrote in the second grade, “The Little Ladybug Who Wanted Antennaes,” complete with the spelling error in the title, so that was clearly an early masterpiece from a marked-for-greatness author (◔_◔).

HN: One of the things that struck me the most about the stories in the collection is the variety of tones that you managed to capture. They range from lyrically fantastic (like “Thirsty Creatures”), to grounded in a harrowing reality (such as “Wolves at the Door and Bears in the Forest” or “Liquid Handcuffs”), to the black humor of the title story and the over-the-top horror-comedy of “The Girl Who Loved Bruce Campbell.” How do you see the variety of tones reflecting your influences? Do you see yourself gravitating more towards any particular type of story as your writing career progresses?

CC: I suppose it would make sense that the horror fiction I write encompasses a wide variety of tones, because the horror fiction and film I consume encompasses that same variability. Of the horror films and television series I watched in the last year, I enjoyed Ash vs. Evil Dead and I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House in relatively equal measure.

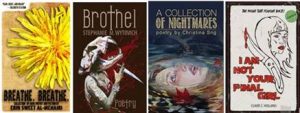

I read across genres regularly, and will find myself reveling in a poetry collection like one of Erin Sweet Al-Mehairi’s, Christina Sng’s, Stephanie M. Wytovich’s, or Claire C. Holland’s, then immediately immersing myself in a no-frills true crime account, like I’ll Be Gone in the Dark. I’ll switch over to a turn-the-pages-so-fast-you-risk-getting-papercuts thriller such as B.A. Paris’ Bring Me Back, followed by a more leisurely literary work like Rabbit Cake by Annie Hartnett.

I love Sarah Water’s Gothic masterpiece, The Little Stranger, in which we barely get a glimpse of the ghost haunting the Ayres family’s dilapidated Hundreds Hall, and Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho, throughout which gore is splattered on every page. My writing style reflects this appreciation for different tones in myriad ways; I can start working on a story that, in my head, looks to be darkly comedic, only to find that it works better without the black humor. I can also outline a story to fit the guidelines of an anthology or other market I want to submit to, then discover that, while the subject matter might remain consistent, the work ends up shifting from, say, a simple haunted house story to a haunted house story that includes commentary on a social issue I’ve been wanting to explore along the way.

I’ve always been a bit helter-skelter in terms of my preferences and endeavors; I am both former substance abuse counselor and former substance abuser. I’m either doing yoga seven days a week while simultaneously training for a half marathon or sticking my nose up at the sight of a gym. I love blood and guts, but cry at YouTube videos of people being introduced to their new puppies. It should really come as no surprise that a double feature in my living room on a Saturday night could consist of twisted French revenge horror film Martyrs followed by the family-friendly Goosebumps, or that the TBR pile next to my bed includes Best Horror of the Year Volumes 1-10, Year’s Best Hardcore Horror Volumes 1-3, and literary works such as Julie Buntin’s Marlena (one of my favorite books I’ve read this year) and Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (one of my favorite books I’ve read of all time).

As for my outlook on the progression of my career, I think I’ll only continue to expand upon the types of stories I go looking to read, and to write. Whether it’s via Cemetery Dance or The New Yorker, I’m always ready to have my temperature changed by a truly fantastic story. I hope that the more I read across genres, and the more I push myself out of my comfort zone, the more eclectic and daring my own stories become.

HN: It feels gauche to ask about an author’s “favorite” or “best” stories in a collection, so let’s come at that in a different way. Which of the stories in this collection was the most cathartic to write? Which did you find the most difficult? Is there one in particular that you’re happy to see collected so that it can reach a wider group of readers?

CC: The most cathartic piece to write out of the stories in my collection was “Flowers from Amaryllis,” but all the stories were cathartic in one way or another, even if that liberation occurred through the simple act of taking an idea from conception to execution. To expound upon why “Flowers from Amaryllis” was the most cathartic, I will tell you that it is also the story I’ve spent more time working on than any other.

I wrote the first draft of “Flowers” more than three years ago. From the start, I was really taken with the idea, which likely contributed to the fact that I didn’t get it right for a long, long time. The story was initially one big info dump, taking the reader through the life of a young woman who’d risen above her substance abuse issues, the loss of her parents, and the trauma of living on the street, with the help of a puppy she’d found one rain-and thunder-filled afternoon beneath an expanse of amaryllises.

The story was clunky, and I’d failed at capturing the emotion I knew existed way down deep at the core of these characters in my head. So I rewrote it. And the rewrite still didn’t do what I wanted it to do. At this point, I decided to walk away from the story to work on other projects. When the time came to put together the stories for this collection, I wanted to include “Flowers,” but knew it still needed a massive overhaul.

I rewrote it yet again, but there was still something off. The story had actually gotten abstract to the point of murkiness; I had lost control of the piece by changing my approach yet refusing to give up on the overarching narrative, despite the fact that it really wasn’t working.

So I rewrote it again, but this time I rewrote it from scratch. I changed the setting, POV, conflict, and much of the main character’s background. The themes, I kept—themes that explored the fear of eventually losing a companion animal, the fear of losing a parent, the fear of being alone, the fear of going mad, the fear of not being able to be true to who you are—and I realized that these themes were what had been driving the story all along. It was a satisfying feeling, matching my prose to the emotion that had spurred me to write the story in the first place.

It’s probably clear to anyone reading this that in addition to being the most cathartic, “Flowers from Amaryllis” was also the most difficult, and subsequently, one of the stories I was most happy to see reach readers, after three long years and a seemingly unending amount of toil. But there are two others I’m pleased to see included in Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked: “This Our Angry Train” and “The One Who Answers the Door.”

Both of these stories were published previously in markets that are unfortunately no longer in existence—“This Our Angry Train” in DarkFuse Magazine, and “The One Who Answers the Door” in wordhaus, where it won the 2016 Trick or Treat Fall Story Contest Best in Genre award—and both are pieces I was loath to condemn to that notorious fate from which there is oftentimes no coming back: getting trunked. (In the case of my work, this would involve an actual, physical trunk in the corner of my living room, where handwritten first drafts go to live out their days, as well as final, typed-up drafts of the ones that didn’t make it.)

With both stories only appearing on the web for a matter of months, I’m thrilled that they’ve had new life breathed into them via Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked. I hope readers find something to love in a story about a lone passenger on a midnight train who finds that the engineer has rerouted them toward a past she’d prefer to forget, and one that follows a quartet of costumed tweens playing at a dangerous game of trick-or-treat.

HN: A number of stories in this collection involve characters who are struggling or have struggled with drug addiction. More than just using it as coloring, you do an excellent job of fleshing out their lives and circumstances in a way that foregrounds their humanity. However, you also aren’t afraid to portray them in a variety of ways—without getting into spoilers, we see these people as heroes, villains, and, in one particular story, literal monsters. Why is portraying these kinds of characters important to you? When you create these characters, what kind of process do you go through?

CC: The reason why it’s important for me to tell the stories of characters who are struggling with or have struggled with addiction is because I have been privy to so many of these stories in the real world.

After graduating from Boston College in 2010 with a Master’s in counseling psychology, I took a job at a methadone clinic in Chelsea, MA, and within a few months had acquired a caseload of over fifty patients. If there’s one thing my work at that clinic taught me, it’s that no two stories of addiction are the same.

Those who want to vilify those suffering from addiction project the same story onto everyone: they are bad, lazy, selfish people who knew the risks when they first used drugs, did so anyway, and so deserve their lot in life. Sadly, many individuals tasked with helping those struggling with substance abuse also assign the same stories to the sufferers. It likely alleviates anxieties over the fact that addiction is very, very complicated: ‘Oh yes, this woman is a heroin addict so her aftercare plan will be methadone; this man is an alcoholic, so a 30-day, 12-step recovery program is for him; Oh, another heroin addict, to the methadone clinic with her,’ and so on.

Everyone’s path into addiction is different, as is—Higher Power Shiva, Pan, or whatever other God you believe in willing— their path out. What that means is that their stories are profoundly unique, and after four years working at methadone clinics, as well as having been a patient in a number of treatment facilities myself, I’ve yet to hear a story that wasn’t worth sharing. This insight has led me to want to explore themes of addiction and recovery within my fiction, believing as I do, that those characters will have rich, interesting, albeit sometimes tragic lives to lead.

As for my process, there’s no real process, per se. I simply write the characters the way they come to me in my head, pulling from my own knowledge and experience in terms of how someone would act when they’re desperate, how someone would act when they’ve relapsed, and are wracked with guilt, or how someone would act when they’re newly sober, and emotionally raw.

As for how someone would act when they’ve shot heroin mixed with toxically altered pond water and became an evil Deadite worthy of Bruce Campbell’s chainsaw? That one might have required imagination as opposed to experience. You can’t—and shouldn’t want to—limit yourself to only writing what you know; I strive to write as honestly as possible, whether it’s on a subject I know intimately or one as far-fetched as zombies pharmaceutically-enhanced to feel no pain.

HN: It seems that many of your stories confront the notion of whether or not it is possible to break out of one’s patterns or have a second chance. Sometimes, like in “This Our Angry Train,” there are characters who cannot escape the choices they made in the past. Other times, breaking the cycle requires great sacrifice—as in “Wolves at the Door…” or “Souls, Dark and Deep”—or else the intervention of great love, such as in “Flowers from Amaryllis.” In what ways have you tried to come at this concept through your fiction? Why do you think it’s such a rich area to explore, either personally or in the horror genre?

CC: I have found the idea of second chances worth exploring in my fiction because the concept of second chances in the real world is such a tricky one. Our society is based on a very unjust, nonsensical system of who is deserving of a second chance versus who is not.

Going back to the issue of substance abuse, if someone like Molly Monteith, in my story, “Wolves at the Door and Bears in the Forest,” is doing her best to rise above her circumstances, but her best is not good enough for the Department of Children and Families; should she be given a second chance? What if she’s on the path to recovery via the methadone clinic, but by virtue of suffering from the disease of addiction, there are bumps in the road? Should we give her the benefit of the doubt? Should we believe that the end—a child staying with her biological mother, a biological mother who loves that child very much—justify the means? What if those means include a relapse? What then?

I don’t know the answers to these questions, which is why I wrote “Wolves at the Door.” In an earlier version of the story, Molly trekked into the woods to relapse because Audrey was actually taken from her by DCF. I changed this because I realized that the story’s power was in its ambiguity. If Molly had been able to hold out one more night, would things have looked better in the morning? I’d like to think they would have, or would have at least started to. Things would have inevitably gotten better by degrees with each day that she stayed clean. But Molly did not stay clean, despite all her willpower to the contrary, and therein lies the tragedy of addiction.

“You hit rock bottom when you put down your shovel,” is a popular AA adage. Molly thought that climbing the mysterious staircase in the woods was the equivalent of climbing out of the hole she had dug for herself. Instead, it is Audrey that is left with a long uphill battle, not to mention a lifetime of what-ifs.

This response was a long-winded way to say that I believe the reward of pursuing a theme that really speaks to you as a writer is in the journey itself, the exploration that takes place over the course of writing a story. I’m certain I will tackle the idea of second chances in another story at some point in the future, and who’s to say if that path will look anything like the one that led me to the stories in Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked.

HN: Speaking of “This Our Angry Train,” I quite enjoyed the way that Joyce Kilmer’s poem “The Twelve Forty-Five” weaves throughout that story. Could you talk a little about how you came to write that story? Did the poem influence the story’s genesis, or did you find the poem after the story idea?

CC: On July 18, 2016, I attended an event at Brookline Booksmith, which featured Joe Hill, Paul Tremblay, Kat Howard, and Thomas Olde Heuvelt. Joe Hill ended up mentioning Kelly Link’s “The Specialist’s Hat” over the course of the discussion, and I spent the train ride back to Westerly reading the eerily bizarre and thoroughly unsettling story. Upon finishing it, I experienced this strange half-waking dream during which I became certain I was no longer on the same train I had boarded.

I should take a moment here to say that I’ve had several strange experiences on trains, strange and rather terrible. Without going into the lurid details, I’ve experienced two separate incidents that were the culmination of negligent substance use, though negligent in different ways. One of those incidents almost resulted in my death. I was lucky enough to be rerouted back to the land of the living at the final moment, but suffice it to say that my impression of trains as rolling aluminum boxes of misery, despair, and potential death was solidified.

When I sat down to write my story of a train as an extension of a young woman’s fears that she is not as far removed from the bad decisions of her past as she might have thought, that she may, in fact, be heading backward without even realizing she’d changed direction, my pen couldn’t move across the page fast enough. After completing the first draft, it occurred to me that the story might benefit from an element of connective tissue, some incantation all the characters on this midnight train to madness know, and feel the need to recite.

I knew of Joyce Kilmer from his poem, “Trees,” but to be honest, I Googled ‘poems about trains,’ and found “The Twelve Forty Five” after a minimal amount of research. In the same way that the excerpts from ‘An Oral History of Eight Chimneys’ are weaved throughout the narrative of “The Specialist’s’ Hat,” the stanzas from “The Twelve Forty-Five” are meant to break up Lauren’s train ride fever dream, and ultimately contribute to the mounting horror.

HN: There is a theme that I see in your stories—that appearances can be deceiving and that the same person or situation can be viewed through many different lenses—and I think this is crystallized in your story “Liquid Handcuffs.” In that story, the main character is a drug counsellor who considers the semantical difference between “client” versus “patient” versus “addict,” and—later on—the difference between being captive in a “prison” versus “environment.” Is that sort of difference in perception something that you’re interested in exploring? Sometimes horror fiction deals in black-and-white morals and absolutes, while other times it traffics in the subjective grey areas—where do you see your fiction on this spectrum?

CC: The whole ‘appearances can be deceiving’ concept is absolutely one I’ve been drawn to in my writing. I like the idea of throwing a reader for a loop when they think they have a character figured out, and I think well-played plot twists of the mistaken identity variety are some of the best kinds there are. I use ‘mistaken identity’ as a broad term here, to mean any instance where readers are lead to believe a character will behave in a certain way, or that their personality is of a certain disposition, only to discover the opposite is true.

This can be anything from actual mistaken identity, like Mark Twain’s, Pudd’nhead Wilson, or something like the film High Tension, where the characters’ actual identities are obscured from the viewer, or an instance like “The Lottery,” which, believe it or not, is where the inspiration for my story, “Liquid Handcuffs,” came from. The first time I read “The Lottery,” I had no insight into the story other than it was one of—if not the most—controversial stories The New Yorker had ever published.

Upon finishing it, all I could think of was, “Well, goddamn it, Shirley. I cannot believe you got me thinking all those fine, upstanding New England villagers were family folk, friends, and neighbors. They were monsters, devils, wolves in sheep’s clothing!” “Ah,” I imagine Mrs. Jackson saying back to me, “could they not have been sheep in wolves’ clothing instead?”

I asked myself a question then: how can I craft a story in which I throw the audience for a Jackson-esque—as much as anyone who’s not Jackson possibly can—loop? I decided that the answer to that question would be “Liquid Handcuffs,” a story featuring several different characters struggling with their addictions. I’ll say no more, to keep from giving anything away, but I love when people who’ve read the story tell me they never saw the ending coming, that it took them by complete surprise.

As for where on the spectrum of black-and-white morals vs. grey-scale absolutes my horror falls, I think, like I mentioned before with second chances, that it falls on the grey-scale side. Horror films like Martyrs—in which the victims and villains are clearly delineated—are certainly rewarding, and allow you to appreciate other aspects of the storyline as opposed to the mere distinction between good and evil. But films and fiction that muddle your ability to decide how you feel about the characters at all, those are the ones that pierce your psyche, that worm themselves into the marrow of your bones.

The 2016 Fede Álvarez-directed Don’t Breathe is fabulous in its depiction of ambiguous character morality. Vic, from Joe Hill’s NOS4A2, is an outstanding example of an extremely likeable, extremely flawed character. Victor Frankenstein is the original inciter of literary cognitive dissonance; do we relate to him because he’s the hero of his own tale, and because we sympathize with his plight, or do we hate him because he refuses to take responsibility for the life, and the horror, that he has created? Those questions, for me, are a huge part of the fun of writing and reading horror.

HN: When you’re not writing, you’ve worked in counseling and as a mental health clinician. Here at Hellnotes we all know that horror writers can be some of the kindest and most compassionate people, but what kind of reactions do you get from others when they find out what you write? Do you keep those sides of your life compartmentalized or do you see them integrating behind the scenes?

CC: People are usually friendly, supportive, and inquisitive when they find out I write horror. You also inevitably get asked if you’re a Stephen King fan as a horror writer, which is fine by me, because I certainly am, but it’s funny how he’s the end-all be-all of horror for so many people. There are dozens of amazing horror and dark fiction writers working today, such as Cherie Priest, Gemma Files, Jac Jemc, Alma Katsu, Seanan McGuire, Ania Ahlborn, Caitlín R. Kiernan, Caroline Kepnes, and Sarah Pinborough, to name just a few.

As for compartmentalization, I don’t tend to do this. What you see is what you get with me. I’ve talked horror movies with the patients on the psychiatric unit I work on, and talked about my work in mental health and clinical trial research with other horror writers. There are always people who want to hate on what they don’t understand, but there are far more people out there—friends, family, acquaintances, colleagues, fellow writers, fellow horror lovers, etc.—who are supportive of my recovery and my horror writing endeavors. With all that love and support floating around the stratosphere, why would I let the naysayers get me down?

HN: Finally, what’s coming up on your horizon? Do you have any plans surrounding Something Borrowed’s release, or any other upcoming releases or appearances you want to share? Beyond the concrete and tangible, can you give us a hint as to any new interests or ideas that you’re just beginning to explore?

CC: In terms of the release of the collection, I have the Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked Launch Party at the Savoy Bookshop & Café in Westerly, RI on Tuesday, August 28th. Following that, on October 20, 2018, I will be the featured author at Beans & Books’ at the Bean Barn, 599 Tiogue Ave, Coventry, Rhode Island, from 7-9 pm. From October 12-14, 2018, I will be one of numerous author guests of honor at the Saugatuck StoryFest. The festival is sponsored by the Westport Library, located on 20 Jesup Road in Westport, Connecticut.

As for new interests or areas I’m beginning to explore, I realized just the other day that I’m only a few short stories away from having enough material to put together a second collection. The tone of this one would be a bit different from Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked, but some of the same themes would still abide.

Still, I won’t pursue this until I’ve finished the novel I’m working on. I was surprised by how much additional work came with the release of Something Borrowed…, and so I’ve been beating myself up regarding the last few things I wanted to tinker with on this new book, Coming Down Fast. Now that the collection has been released, I’m going to use that relentless self-flogging for actual good, and finish the damn thing.

Besides Coming Down Fast and the new collection, there’s another novel I have in the works. Staying extraordinarily busy sustains my passion for this crazy thing I love to do. Hemingway said it best; there really is nothing to writing. You do just have to sit at a typewriter and bleed. Now, where is my knife…?

Christa Carmen’s work has been featured in myriad anthologies, ezines, and podcasts, including Unnerving Magazine, Fireside Fiction, Year’s Best Hardcore Horror Volume 2, Outpost 28 Issues 2 & 3, Tales to Terrify, Lycan Valley Press Publications’ Dark Voices, Third Flatiron’s Strange Beasties, and Alban Lake’s Only the Lonely. Her debut collection, Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked, is available August 2018 from Unnerving.

Christa lives in Westerly, Rhode Island with her husband and their bluetick beagle, Maya. She has a Bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in English and psychology, and a Master’s degree from Boston College in counseling psychology. She is currently pursuing a Master of Liberal Arts in Creative Writing & Literature from Harvard Extension School. On Halloween 2016, Christa was married at the historic and haunted Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado (yes, the inspiration for Stephen King’s The Shining!). When she’s not writing, she is volunteering with one of several organizations that aim to maximize public awareness and seek solutions to the ever-growing opioid crisis in southern Rhode Island and southeastern Connecticut.

Author Website: www.christacarmen.com

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/15179583.Christa_Carmen

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/author/christacarmen

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/christaqua

Twitter: https://twitter.com/christaqua

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christaqua/

Something Borrowed, Something Blood-Soaked: https://www.amazon.com/Something-Borrowed-Blood-Soaked-Christa-Carmen-ebook/dp/B07DK2YJV3/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1531331264&sr=8-1&keywords=something+borrowed+something+blood-soaked

Outpost 28 Issues 2 & 3: http://www.deankuhta.com/outpost28.php