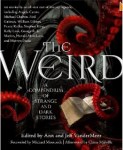

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, editors

Tor Books

Trade Paper, 1152 pages, $29.99

Review by Sheila M. Merritt

Too much of a good thing; we’ve all been there. The favorite Halloween candy that we stash away from the kids, hoping that after a certain hour it will be ours and ours alone. And then consume it way too fast. Those lengthy nocturnal fantasies about Alan Rickman: Yeah, oh yeah. Regarding the much too good volume entitled The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories, we so don’t deserve it. It demands to be savored, but horror readers are a greedy bunch and tend to devour quickly. Which is a shame, since the tome sits warmly on the lap, whether opened or closed. Contained in the voluminous collection are tales from well-known writers. To list them all would take up a great deal of space. Suffice to say, some of the names will ring a genre fancier’s bell: Gaiman, King, Kafka, du Maurier, Lovecraft, Blackwood, Leiber, Bradbury, Jackson, Bloch, Aickman, Campbell … you get the drift. The beauty of the tome is that, in it’s over 1000 pages, authors who didn’t/haven’t reached that magnitude of fame still get to strut their stuff. This review will focus on those writers’ works, one from each era represented in the book. Therefore, in chronological order:

From 1913, comes the amazing “The Dissection.” Point of view animates the yarn. Doctors dissecting a corpse aren’t concerned with the body prior to death: “From their white cabinets they took out dissecting instruments, white crates full of hammers, saws with sharp teeth, files, needles like vultures’ crooked beaks forever screaming for flesh.” The man who has died, however, maintains memories. He recalls the woman he loved: “The decay pulled apart the mouth of the dead man. He seemed to smile. He dreamed of beatific stars, of a fragrant summer evening. His rotting lips trembled as though under a brief kiss.” The disparity between the clinical and sentimental is superbly rendered.

“The Dissection” was written by Georg Heym, and the translation from German by Gio Clairval is commended by editors Ann and Jeff VanderMeer. Also of note in the story’s introduction is “Master of the weird Thomas Ligotti has called it one of his favorite tales.” This is high praise, indeed.

In 1921, Stefan Grabinski’s “The White Wryak” was published. Some critics called Grabinski the “Polish Poe” or the “Polish Lovecraft.” Certainly, looking at the story in this anthology, it can be said that he felt at ease with weird fiction. The bizarre entity that he concocted is highly memorable: “The creature – part monkey, part large frog – was holding in his front claws what seemed like a human arm, which hung limply from a corpse, vaguely outlined in a twisted shape next to a neighboring wall.”

H.P. Lovecraft’s name is again brought up, in a different context, in “Far Below.” Published in 1939, and written by Robert Barbour Johnson, Lovecraft’s work is mentioned by a character in the yarn as having historical truths and verisimilitude. Creatures are lurking in a stretch of the New York City subway system; a secret that is kept from the citizens of the metropolis. Claustrophobic and conspiracy oriented, “Far Below” does definitely have a Lovecraftian vibe.

Culturally and stylistically far different is 1949’s “A Child in the Bush of Ghosts.” The author, Olympe Bhêly-Quénum, moved from Africa to France in the late 1940s. He still resides there today. The surreal ghost story included in this text is set in the writer’s native land. It is splendidly ambiguous and atmospheric.

Also surreal is the allegorical “A Woman Seldom Found.” Ostensibly a romance set in Rome, William Sansom’s tale is a take on the nerd meets the girl of his dreams theme. Of course, she turns out to be the stuff of nightmares. First published in 1956, a time that prided itself on a rather contrived innocence, the intimacy between the guy and gal leads to a shocking climax. What the woman of the title represents can be interpreted in many ways, but going for the Freudian is simplest.

A contribution from French fantasist Claude Seignolle doesn’t obviously reflect reference to its period (1967.) In “The Ghoulbird,” Seignolle plays with residual folklore and superstition. The fearsome fowl is eloquently described: “Its appearance was not at first frightening, and it could look like any common bird, but shifted continuously from one species to the next to fool its victims. In its call, an additional note rang out…a bit strident. It was the Ghoulbird’s curse…To listen to it was to lose one’s will to the bird and forever be the creature’s slave.”

In an interesting twist at the end, the first person narrator discovers that fear can cloak reality; creating misunderstanding. “My Mother” also delves a bit into perception and interpretation, but the 1978 tale is primarily about change and adaptation to it. The story’s scribe, Jamaica Kincaid, is a Caribbean writer who dwells in The United States. Incorporating nurturing females into a socio-political fantasy, Kincaid nicely fuses the elements.

Nigerian Ben Okri’s offering from 1988 is what the VanderMeers refer to as “a form of ‘African magic realism.'” “Worlds That Flourish” could also be construed as possibly being influenced by Kafka’s novel The Trial. In both pieces, the respective cultures oppose an individual; making the protagonist at odds with his society. Persecution, delirium, and resignation are effectively rendered in this passage: “The rice seemed to move on the plate like several like several white maggots. I could have sworn it was covered in spider’s webs. But it tasted sweet and was satisfying. The cup from which I was supposed to drink bled on the outside.”

The award for most-tender-yet-whimsical narrative goes to “Last Rites and Resurrections” by Martin Simpson. After the death of his young son, a man becomes obsessed by the roadkill he sees on his drives. Getting out of the car to get a closer look at a dead basset hound, the guy discovers that he can hear the canine’s last thoughts. He takes the dog back to his property for burial. Over the course of the story, many critters share their final musings with the fellow, and he provides them with his version of a pet cemetery. The articulate animals speak English, but with patterns unique to their species: “Some animals sound like you would expect them to sound, if you expected them to talk: dead dogs speak quickly and with tangled syntax that often produces circular sentences, while deceased cats are slower and more careful, measuring out the meticulous pronunciations of a Latin teacher. Squirrels communicate in staccato snippets that sound vaguely like Vietnamese to my ears. The posthumous speech of two other species I also associate with foreign language accents: the wry humor of armadillos comes wrapped in the harsh back-of-the-throat consonants of German, while clever raccoons trade in the nasal delicacy of French.”

Simpson’s 1994 delight is touching and funny and dear. The author manages to convey extraordinary depth of feeling while employing seemingly matter of fact prose. Much edgier and darker is “The Hide” by Liz Williams. Sibling jealousy is metaphorically explored in this strange 2007 dark fantasy. Suppressed emotions surge during the benign act of birdwatching. While venturing a bit into the terrain of du Maurier’s novelette “The Birds,” the events that transpire in Williams’ universe are much smaller and specific in scope. Tidy in structure and containing just the right amount of odd to be quietly disturbing, “The Hide” is a marvelously titled piece.

The Weird is a book that is chock full of goodies. And editors Ann and Jeff VanderMeer deserve special praise, not only for the excellent selection of the 110 stories, but also for their acknowledgement of the translators of material not initially printed in English. Giving those diligent language interpreters a well deserved shout out is positively classy. How best to appreciate this wonderfully large volume is a matter of personal choice. It can be slowly absorbed in increments, or hastily read in a fervent horror fiction marathon blowout. Either way, the time spent will prove extremely gratifying.

[Editor’s Note:] Sheila Merritt has been with Hellnotes almost since the day of its birth. She’s contributed over 250 book reviews, author interviews, convention reports, and more. She’s worked tirelessly and made Hellnotes better for her efforts. Now, she’s stepping back to enjoy all the other passions of her life. I want to personally and public thank her for sharing her talents, knowledge and enthusiasm with Hellnotes. Thank you, Sheila!